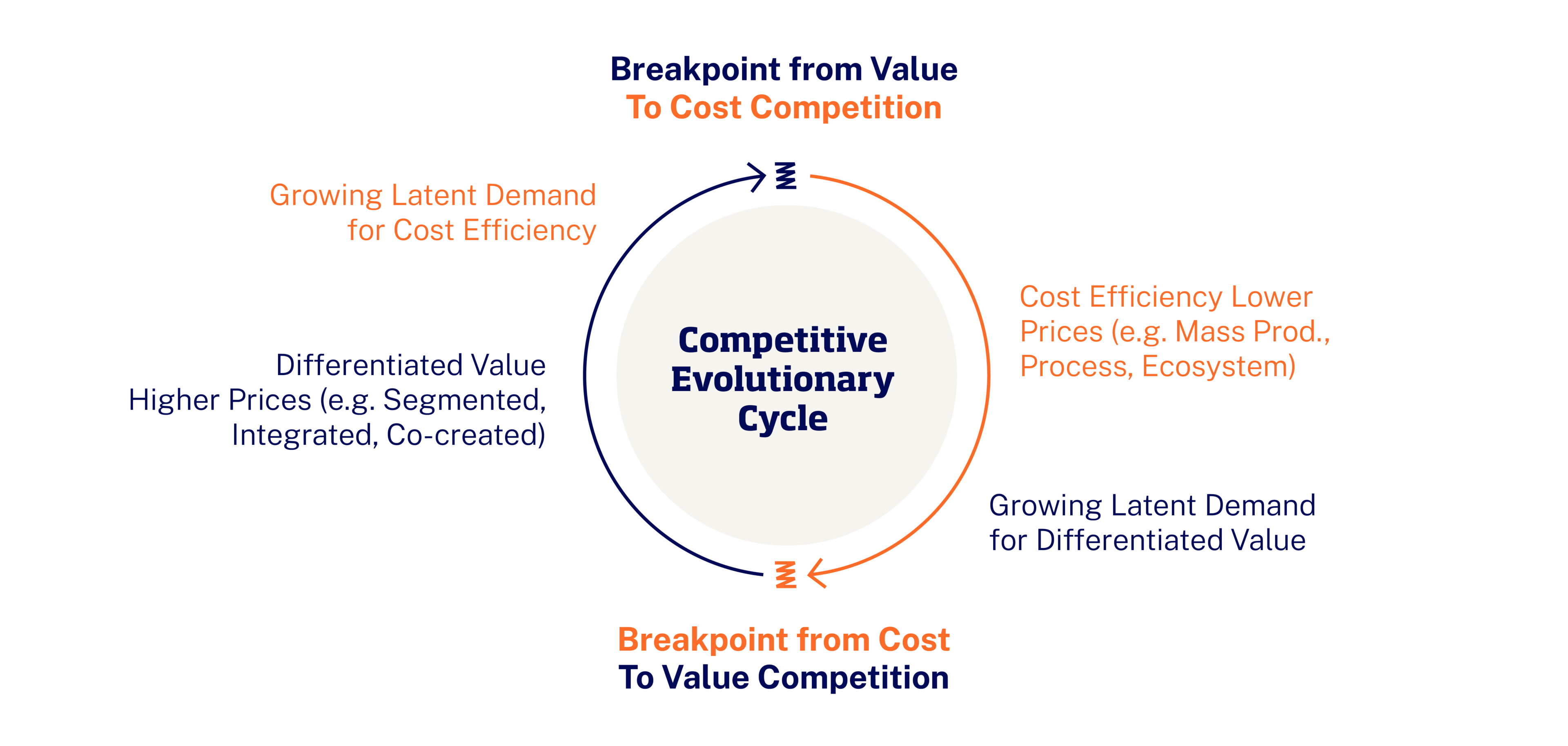

Between bursts of disruptive innovation, industries move through competitive cycles – first divergence and variety creation, emphasizing differentiation to stand out, then shifting towards convergence around the best variants, emphasizing efficiency to cut costs. Companies that successfully manage the transition points between value differentiation and cost efficiency, and, conversely, can outperform the competition. This is what my colleague Xavier Gilbert and I have termed outpacing strategy.

Take the automotive industry as an example. With the mass production of electric vehicles, Tesla’s disruption of this sector has been followed by a scramble among existing American and European players to catch up. The Chinese market, on the other hand, is full of startups competing ferociously to attract a growing middle class of restless consumers, providing the natural breeding ground for the evolutionary breakpoints companies can exploit to get ahead.

Leading Chinese companies, like BYD, are outpacing competitors by shifting the focus in the lower end of the market from differentiation to manufacturing efficiency, thanks to their low-cost batteries and charging times. In the upper end of the market, Xiaomi is shifting the competitive focus in the other direction, to differentiated distribution, by integrating the car into a lifestyle system of interconnected mobile and home appliances.

Outpacing strategy shares two key features with what Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne refer to as Blue Ocean strategy, defined as, “The simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low cost to open up a new market space and create new demand.” The first key feature is the objective of creating an uncontested market space rather than fighting over existing demand, and the second key feature is unlocking new demand rather than stealing rivals’ customers. But rather than the simultaneous pursuit of differentiation and low cost advocated by Blue Ocean strategy, Outpacing strategy highlights the importance of alternating between differentiation and cost to create competitive advantage by capitalizing on the opportunities created by the evolutionary cycle of competition.