Digital business transformation (DBT) is happening on a scale and at a speed that managers find both threatening and promising. In a report entitled “The Internet of Everything,” CISCO Systems estimated that 10 billion devices were connected to the internet in 2013, and predicted that this number would rise to 50 billion by 2020. It further projected that $14 trillion in business and economic value would be at stake between 2013 and 2020 across nations, industries and companies through business innovation, higher productivity, increased efficiency in processes, and enhanced customer experiences.

The benefits of DBT are tremendous, but they are unevenly distributed. A 2011 IBM/MIT study concluded that there was a widening divide between companies in how they leveraged analytics and data for business value. In this article, we help define what DBT means for your company and provide a roadmap for creating and capturing value from digital tools and technologies. At its core, DBT is as much about organizational change as it is about technology, and we offer a framework to help navigate this change and realize DBT’s full potential.

Digital business transformation: Definition and key elements

The roots of DBT can be found in MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte’s 1995 book Being Digital which explored the substitutability of bits and atoms. Negroponte suggested that any form of information that exists as atoms (like books and DVDs) can be represented by bits on a digital device. This fundamental insight formed the basis of the early growth of e-commerce, as well as the widespread deployment in more traditional industries of information systems, for example for shipment tracking by FedEx, inventory management by Walmart, and the daily tracking of purchases of millions of Frito-Lay snacks by its sales route drivers. The leaders of these companies understood that digital information about their products (and customers) was as important as the products themselves for boosting business performance against their less digitally aware competitors.

Since then, organization shave widely implemented digital technologies, modified processes to be digitally enabled, and generally become more digitally savvy, but often in an ad hoc manner, without an overarching structure or strategy. Here, we view DBT as a journey that must be approached and navigated mindfully. We define digital business transformation as organizational change through the use of digital technologies to materially improve performance.

AMPS: The newest digital technologies

Digital leaders are companies that manage to harness the power of digital information and technologies to improve business performance. It is important for managers to be aware of digital technologies that have the power to enable and transform their businesses. We refer to the current wave of these technologies as AMPS. Together, these four digital technologies are having a profound effect on how organizations and industries are transforming, as outlined below.

Analytical tools and applications

These tools and applications are designed to analyze and extract value from the vast amounts of data available to organizations today. The difference between this “big” data and traditional forms of data is related to the three Vs: volume,or the sheer amount of data; variety, or the many different types of structured and unstructured data; and velocity, or the speed at which new data is being created. Oil and gas companies, for example, use sophisticated geological and historical data to better understand where to drill multi-million dollar holes to extract more oil from existing reserves.

Mobile tools and applications

More people connect to the internet today through mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets than via fixed devices like PCs. As a consequence, many companies are pursuing a mobile-first strategy, whereby application development is targeted first at mobile devices and then later modified for computers and other fixed devices. For example, Streetline provides apps to monitor parking space availability in large cities to save delivery drivers and consumers fuel and time in locating parking spaces near their intended destinations.

Platforms to build shareable digital capabilities

Many traditional systems and processes are proprietary, meaning that the underlying data and insights cannot easily be shared. Digital platforms are non-proprietary systems that can facilitate the sharing of data, applications and insights across different parts of an organization. Digital libraries of content and applications are being developed to allow for the sharing and reuse of valuable business resources. For example, programmer improvements to the Linux operating system code and applications are freely available in digital libraries on the internet.

Social media

Social media applications like Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter allow for a two-way flow of information and communication between an organization and its key internal and external stakeholders. They can also be used as learning tools to monitor industry trends, customer sentiment and competitor moves.

The organizational change imperative

Digital business transformation is not just about deploying AMPS in the workplace. Technology implementation without accompanying org- anizational change is likely to result in suboptimal outcomes. Indeed, the benefits of DBT can only be achieved with the right blend of people, skills and organizational structure.

The first challenge is for business leaders to create a sharing culture in which people are encouraged to express and use their internal and external knowledge for the company’s benefit. Command and control models of running organizations do not work in the digital age. Nor do organizational cultures that rely too much on individual performance, instead of team collaboration, to solve business problems.

The second challenge is to develop and promote a mindset of curiosity, fostering people’s appetite to better understand what they know and, more importantly, what they don’t know, and link this knowledge to decision-making and business benefits. For example, companies like Intel must invest in microchips well before their uses emerge in specific markets – a form of intelligently sensing where future markets will exist for its products.

The third challenge is to cascade an information- oriented culture throughout the company, and beyond, to customers and partners, to co-create value and innovation through smarter use of digital tools and real-time information. Do managers in your company use digital technologies to cultivate values and behaviors associated with the information integrity, transparency, trust and sharing that digitally based business processes and models require? Going digital is as much about transforming the knowledge- and information-based culture of a company as it is about using new digital technologies.

The fourth challenge is to selectively prioritize emerging business areas that leverage digital tools and technologies, while still seeking to optimize areas that are challenged by these changes. Finding the balance between new and established areas can be extremely tricky. For example, multi-line insurance companies have relied for decades on large networks of physical agents who live and work in their clients’ communities. Today, insurance is increasingly being researched and purchased online, with little or no interaction with physical agents. Thus, insurance companies need to develop digital capabilities to design, promote and sell policies through digital channels, while continuing to leverage the strength of their offline network.

Digital business transformation is about smarter performance

Combining digital technologies with the organizational and people changes required to build a digital information-oriented culture allows organizations to significantly improve business performance. Here, we believe that there are six specific areas of performance improvement:

Capturing and using real-time data about customer experiences for smarter sales interactions

Monitoring and tracking information about product, service and solutions support for continuous improvement

Sharing knowledge and information more effectively to act across functions and organization boundaries

Applying deeper and more targeted analytics that enable better decision-making

Deploying more efficient and agile processes and systems to react to rapid business change

Adopting more innovative and resilient business models to create disruptive change and innovation in a particular industry.

While most executives would like to measure digital business transformation in terms of increased revenue and decreasing costs, we believe these are lagging indicators in most companies. In our experience, improvements in these indicators will follow from developing leading indicators for the six areas of performance improvement noted above.

Digital business transformation: Where are you on the journey?

Many managers in companies with strong non- digital capabilities struggle with the challenges of “going digital.” Established firms complain that they are encumbered with legacy “non-digital” assets and capabilities, and look with envy at emerging competitors. But the opposite is also true: Emerging digital players covet the resources available to traditional firms, such as established brands, access to capital, deep product and industry knowledge, and strong networks of relationships with customers and other relevant stakeholders. All these advantages can be leveraged by traditional firms as they transition into new digital areas.

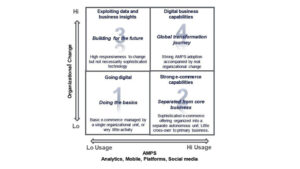

Figure 1 provides our framework for digital business transformation. The horizontal axis focuses on the deployment and usage of AMPS, while the vertical axis focuses on the degree of organizational change. Upward or outward movement on these axes is required to achieve the full benefits of DBT.

Figure 1: Digital Business Transformation Framework

Quadrant 1: Going digital – doing the basics

Many companies with strong non-digital assets and capabilities are still in the “experimentation phase” when it comes to digital. Over the past ten years, they have developed websites, intranets and some extranets to link suppliers and partners. They have also spent heavily on back-office enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems and IT infrastructures. Most managers and employees use mobile phones and PCs, and there may be pockets of e-commerce in different subsidiaries and functions. However, these managers do not have the mindset to seriously move toward exploiting digital technologies, nor do the companies have the business strategies to do so.

While senior managers may talk about going digital, they are often not active users of digital technologies themselves. They believe these tools are for younger generations of workers, not for top teams. While the IT organization and some business units will deploy and use digital sites within the company, the use of digital to monitor customer contacts, experiences and complaints is minimal. Digital communities and information sharing may occur inside the company and across units and functions, but it is largely voluntary and not actively encouraged by senior leaders.

Since digital technologies and organizational change are minimal, so are the business improvement benefits of going digital – a circle of irrelevance! Lagging indicators of revenue and costs are used, traditionally with little connection to digital investments or changes.

Quadrant 2: Strong e-commerce capabilities– separated from the core business

In established industries such manufacturing, distribution, process and chemicals, many companies have developed strong and sophisticated e-commerce capabilities, either as autonomous e-sales and service units or as “bolt-on” e-commerce capabilities. These endeavors typically have little coordination with, or impact on, organizational functions such as manufacturing, R&D and distribution. Senior managers in these companies recognize the importance of going digital in sales and marketing, but have not discovered the “internet of things” where digital technologies are linked in machine-to-machine (automated assembly by robots) and machine-to-people (navigational safety systems to avoid collisions in cars) applications.

For example, in distribution-oriented industries such as plumbing or electrical supply, leading companies have developed pockets of e-commerce, but have yet to develop business strategies that leverage product information to co-create solutions for installers or building contractors. Senior executives in these companies believe that the product expertise and knowledge of their people is best exchanged in face-to-face interactions with business customers in branch networks and building sites, rather than through digital channels. Thus, their non-digital business models are subject to gradual erosion linked to the digitalization of product knowledge by their suppliers and commercial customers.

A danger for companies in this quadrant is that because they have developed e-commerce capabilities, they believe they have “gone digital.” An e-commerce business unit might be successful, but unless digital capabilities and knowledge are integrated into the larger legacy organization, the benefits of DBT are isolated.

Quadrant 3: Exploiting digital data and business insights – building for the future

Some companies have developed strong digital capabilities without large investments in technology assets. Over the past six or seven years, many established companies in more traditional industries – such as oil and gas, nutrition and wellness, and construction materials – have responded to rapid changes in internet use by targeting specific uses of AMPS inside and outside their companies. For example, Nestlé has developed highly responsive teams of digitally aware marketing and IT people at its headquarters to monitor what consumers around the world are saying (social media sites) and seeing (YouTube) in connection with Nestlé products.

Other companies have built on an established operating culture of continuous improvement and innovation to accelerate process improvement efforts throughout the company. CEMEX – a leading global supplier of cement, concrete and aggregates – has organized hundreds of targeted virtual process improvement teams across its local operating companies using social media technology and company intranets. These efforts have improved collaboration among local teams as well as across regions in the midst of the global financial and construction industry crises. In oil and gas, senior executives of Ecopetrol in Colombia have embarked on a five-year journey (starting in 2010) to develop a digital business enterprise. They believe these digital capabilities coupled with non-digital assets will best prepare their company to compete in the regional and global oil and gas industry.

Quadrant 4: Digital business capabilities– a global transformation journey

Companies that have reached this quadrant have successfully combined strong AMPS adoption with real organizational change, and they evolve continually. Disney, for example, although not a newcomer to digital transformation in its entertainment and educational businesses, is leveraging its non-digital assets. The company has invested $1 billion to roll out “smartband” technology, called MagicBand, for consumers to wear in its theme parks. The objective is to track and improve the customer experience across all services delivered in a Disney park including hotel reservations, hospitality services and the many rides and attractions. The project, known as MY Magic+, aims to ensure that Disney’s 30 million annual visitors have the best possible experience in its parks and facilities, while increasing consumption of Disney services and attractions to increase revenue and profits from its non-digital assets, in this case theme parks.

Navigating the digital business transformation journey

Digital business transformation has been moving steadily through both developed and emerging economies over the last 15 years. The mix of digital and non-digital capabilities has continued to change in different industries. Tourism, banking, entertainment and retail have been in the vanguard of this change. Transportation, insurance and healthcare are emerging quickly. Over the next decade, all industries will be transformed either by new players disrupting established ways of doing business or by established players whose leaders believe that digital transformation is a competitive imperative now and in the future. When we examine DBT in pharmaceuticals, insurance and other industries, seven factors stand out:

Clarity of purpose is essential. Senior managers must have the vision and competence to lead digital transformation in their companies.

The change must include the frontline workforce. In one global healthcare company, the president of the pharma division led the deployment of 25,000 iPads to the global sales force to empower frontline representatives to improve customer engagement with better customer and product information.

Digital transformers must understand the need to invest in AMPS and technology platforms that are sufficiently robust and flexible to be implemented and utilized throughout the company.

Managers must develop people’s ability to effectively use information, as analytics becomes an increasingly large part of the competencies of the workforce on all levels.

Senior executives must take the lead in modeling the values and behaviors associated with effective knowledge and information use in the digitally enabled company – integrity, transparency, trust, sharing and proactive use of knowledge for decision-making starts at the top.

Measuring progress on the journey to developing digital business capabilities is essential for maintaining momentum for continuous improvement. DBT is a journey, not a destination!

Executives must balance an execution-oriented culture with the inevitability of disruptive change in and across industries. This is the “new normal” for many established companies going forward – the adoption curve of AMPS is accelerating, not slowing, in the global economy.