The challenge of setting ambitious targets as a leader

Executive coach Angelica Adamski shares the challenges facing Lyndsey in aligning and leading a new and globally dispersed sales team....

by Simon J. Evenett, Felix Reitz Published 3 October 2023 in Finance • 13 min read

Never afraid to provoke, when asked about doing good in 1980, Margaret Thatcher replied: “No one would remember the Good Samaritan if he’d only had good intentions – he had money as well.” This comment resonates today as societal demands on businesses grow and grow. Just how much surplus does capitalism create that could then be deployed for the benefit of its stakeholders? For example, how do those amounts compare to the costs of attaining net zero or implementing the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?

Despite capitalism existing for millennia, there aren’t widely used economy-wide measures of corporate value creation – how much surplus value businesses deliver in the course of their operations, once all their costs are deducted. For sure, there are macroeconomic aggregates but their link to firm performance is indirect, at best. We were determined to fill this major data gap with the “Crux of Capitalism” project – the first attempt to build a bottom-up measure of firm value creation for publicly listed companies in 21 of the world’s major or most successful economies. Those economies include the largest by GDP plus a range of successful smaller ones such as Switzerland.

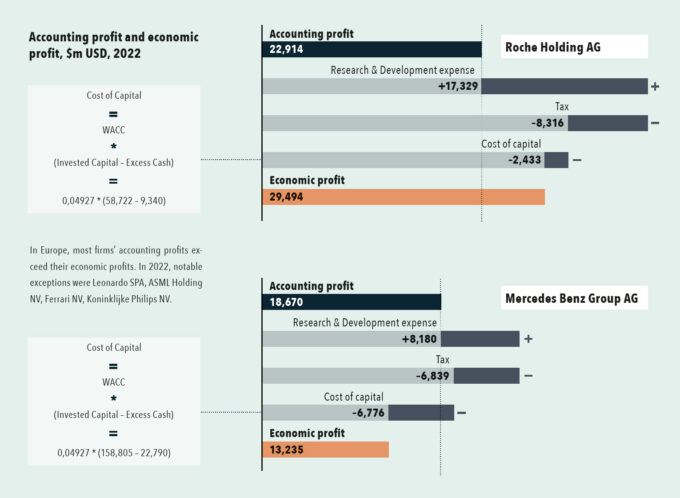

Fortunately, we could adapt “economic value added” measures of firm performance (operating profit less the cost of raising the firm’s capital) to create a measure of a company’s economic profits, which offers a truer reflection of the value created or destroyed by a firm than its accounting profit (Stern Value Management, a management consulting firm, proposed economic value added as a measure to calculate the true economic profit of a company in the 1990s). In Econ 101 courses, students learn that the difference between economic profits and accounting profits is that the former takes account of the income investors in a firm could have earned if the investors had deployed their capital elsewhere. Failure to factor in this “opportunity cost” artificially flatters the corporate performance of asset-heavy companies, in particular.

As the goal is to quantify how much a firm’s current operations generate total revenues above its operational costs (including the opportunity costs of capital owned by the firm), other adjustments are needed too. Adding back in R&D expenses (a non-operational, voluntary expense) and deducting taxes tend to be the two biggest adjustments. Altogether, economic profit reveals how much value or surplus a firm has created in a given year. Against this, some might want to deduct the environmental or social damage inflicted by a firm. We didn’t do that because our goal was to learn the maximum amount of resources a firm has at its disposal to take on any challenge, including rectifying any damage it has caused.

As the graph above illustrates for two household names, companies differ a lot in their levels of recorded economic profit, depending on the amount they invest in R&D, how much tax they pay, and what their cost of capital is in any given year. For example, pharma giant Roche’s economic profit exceeded its accounting profit in the 2022 financial year by some margin, largely due to a significant investment in R&D and its low cost of capital. In fact, Roche had just under $30bn to deploy on whatever commercial and other priorities its management decides upon. The economic profit of Mercedes Benz, however, fell below its accounting profits due to a lower R&D budget and a higher cost of capital.

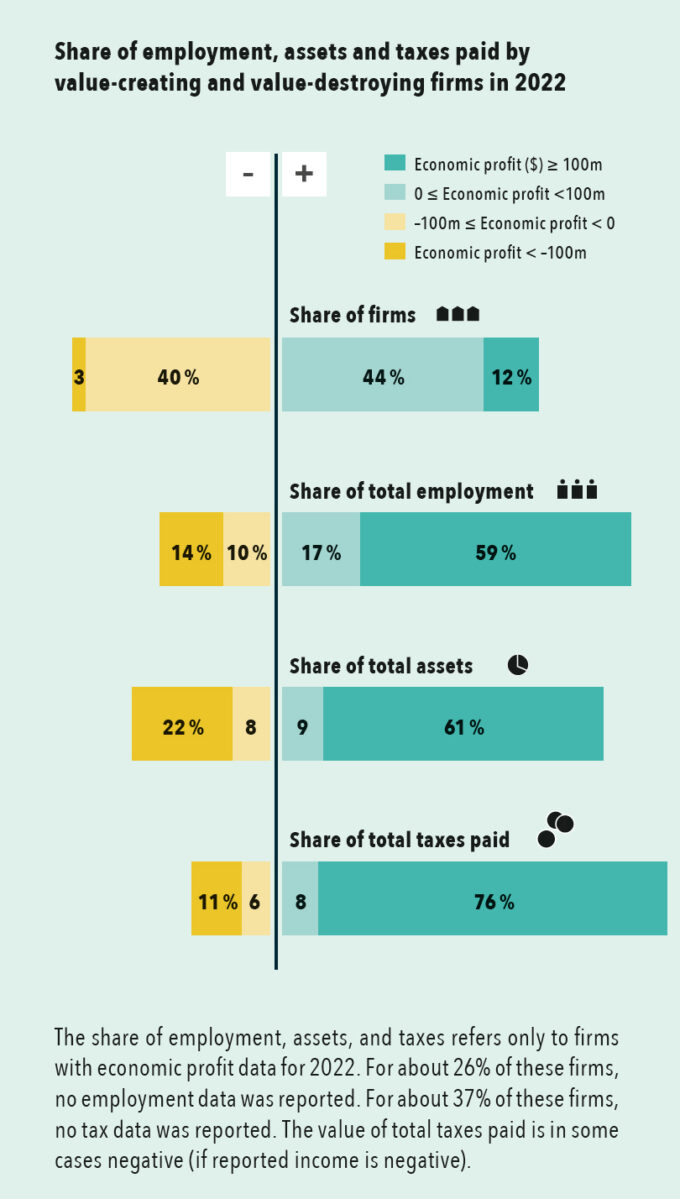

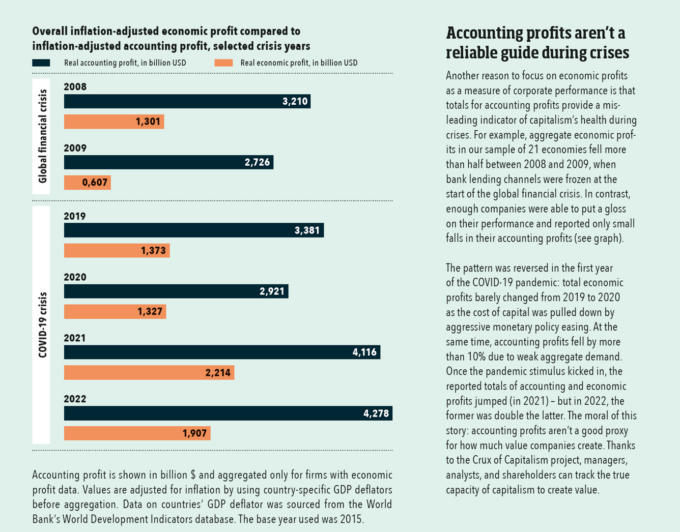

From the perspective of getting the most bang from a society’s resources, one disturbing finding is that some firms can report positive accounting profits while their economic profits are negative. That means a firm’s current operations cannot cover its full operational costs – in short, it destroys value. The graph below shows that of the more than 17,000 firms we have data on in 2022, 3% of them have economic losses exceeding $100m. Now, a firm having economic losses for a year or two as it turns around may not be problematic, but hard questions should be directed toward the management of firms that sustain economic losses over many years. Reasons for underperformance differ. Some have lower productivity levels, worse records of operational efficiency, or have inherited high or rising cost bases – all of which push firms into negative economic profit territory. These firms burn investors’ funds, which is economically inefficient because the capital invested into them could be employed in more productive ventures instead, leading to higher overall productivity growth. A total of 14% of employees and 22% of assets are invested in firms that made economic losses exceeding $100m in 2022. Taken together, last year a quarter of employees in our huge sample work for value-destroying firms and these firms deploy 30% of all corporate capital. The reason countries need competitive markets and effective bankruptcy laws is to induce management of these companies to shape up, hand the reins over to others, or release talent and capital to other value-creating sectors of the economy.

But looking at the graph from the perspective of successful value-creating firms (those making more $100m or more in 2022), we can see that these firms account for 59% of all employees, absorb 61% of corporate assets, and, critically, contribute 76% of all corporate taxes paid. Firms that generate lots of value also contribute the most to public finances – a finding that undercuts a lot of the critics of capitalism.

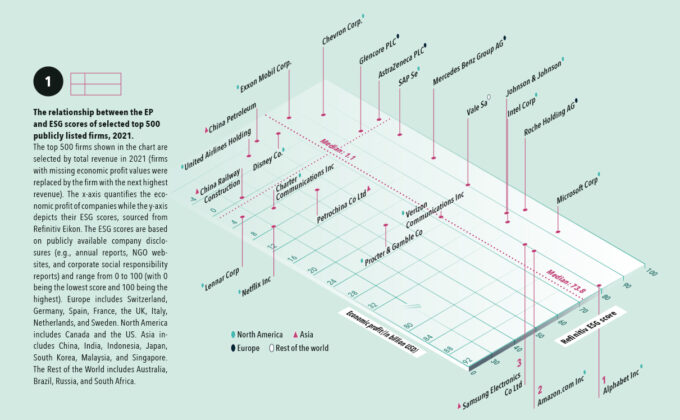

For those putting a premium on responsible business conduct, capitalism creating value doesn’t cut it if it comes at the expense of cherished environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals. So, we examined the 500 firms with the largest revenues to see how economic profit (EP) performance related to ESG ratings recently and over time.

We sourced ESG scores from Refinitiv Eikon, a financial market analysis tool, and compared them to economic profits as a share of total revenues (which effectively scales EP performance). For 2021, we plotted ESG scores against these economic profit margins for the 500 firms (see chart 1 below). To help interpret the plot, we added dotted lines for median ESG score and median economic profit performance. At first, the plot looks random but it turns out that the quadrant with above average EP and ESG performance contains 29% of firms, and the quadrant that has below average EP and ESG performance contains another 29% of firms.

This finding means that any notion that there is an inherent trade-off between high ESG scores and strong EP performance can be discounted – there are plenty of firms firms where management has taken steps to deliver both. It’s time to revisit assumptions that investments in firms that deliver more on ESG don’t pay off financially. Maybe that applies in some noteworthy cases, but they are the exception, not the rule.

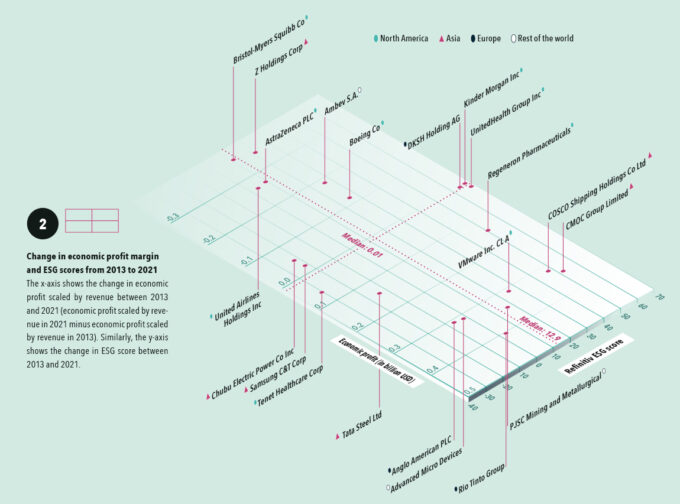

But what about performance over time? Do firms that want to boost economic profits have to do so at the expense of their ESG scores? For the same 500 firms, chart 2 (above) plots the change in ESG score against the change in economic profit margin from 2013 to 2021. It turns out that almost a quarter of firms are found in each quadrant of the chart. Some firms found ways to deliver better EP and better ESG performance. On average, ESG scores rose 12.9 points from 2013 to 2021, but average EP margins barely moved. These findings don’t support a broad-brushed critique of capitalism, but they certainly beg questions about win-win formulas and why some firms felt they could buck pressures to improve ESG performance.

Given the large debts many governments took on during the COVID-19 pandemic, their ability to finance the transition to net zero, attain the UN SDGs, and cope with the costs of aging populations is in doubt. Consequently, some look to the private sector as a pot of gold to finance these social imperatives. For their part, if their public statements are anything to go by, many corporate executives plead with governments for subsidies to accelerate the energy transition and digital transformation. So just how much money does the private sector have to spare after it has paid its operational costs in full? That’s where our aggregate economic profit measure comes in.

Using current exchange rates in 2022 and summing across the 21 economies in the Crux of Capitalism project, we estimate that firms generated a total of $2.2 trillion dollars in economic profit. When careful corrections are made for the fact that not every firm has reported its financial results, we reckon about $2.725 trillion of economic profit was made in these 21 economies. Is that a lot or a little?

Graph 3 (above) provides instructive comparisons. McKinsey & Company estimates that financing net zero worldwide requires an additional $3.5 trillion every year. If that’s right, then firms in these 21 economies have the resources alone to foot over 78% of that bill. For sure, that would wipe out R&D budgets, but this calculation provides context and, indirectly, highlights the trade-offs at stake.

What of the SDGs that governments agreed in 2015 must be reached by 2030? The financing gaps calculated by a range of international organizations for ending hunger (SDG 2), achieving health goals (SDG 3), and assuring access to safe drinking water (SDG 6) amount to $525bn per annum. This amount is less than a fifth of the total economic profits created by the 21 economies examined here.

Country-specific comparisons are possible too. The Federation of German Industries (BDI) and BCG estimate that the yearly cost of reaching climate change targets at $110bn. That’s a sixth less than the total estimate of German economic profit in 2022, $133bn. Here it is worth pointing out that many successful German firms don’t list on the stock market, so the overall economy-wide EP of all German firms will be significantly higher. If German businesses can continue to deliver 2022 levels of economic profit, then the resources are there in the private sector to attain climate targets without subsidies from Berlin.

Care is needed here in drawing conclusions. First, economic profit acts as a reward for innovation, corporate improvements, and the like. Tax all of it away for any purpose, good or ill, and extrinsic incentives are blunted. Still, the point is that, at the moment, the corporate Samaritan has the money.

Second, the recorded levels of total economic profits in 2021 and 2022 were around a third higher than in 2018 and 2019, the two years preceding the pandemic. The ongoing phase-out of COVID-19-related and more recent fiscal measures as well as moves towards interest rate normalization and the resulting rise in the cost of capital will reduce total levels of economic profits. All of this underpins why it is so important not just to track economic profit but also to design policies that enhance legitimate firm value creation. It is in no one’s interest if the corporate goose stops laying golden eggs.

No organization can escape the need to transform to become more sustainable. The need to act is urgent. It calls for strong leadership, difficult decisions, and deep cultural change. In Issue XI, we explore how to build sustainable organizations to succeed in turbulent times.

Business plays a crucial role in addressing the problem of climate change. Firms create the technologies and infrastructure necessary to transition to a carbon-neutral economy, but they are also significant emitters of greenhouse gas (GHG). These emissions account for a considerable share of the global annual GHG budget and originate either from sources that a firm controls directly (what are referred to as Scope 1 emissions), or indirectly (Scope 2), for example, when purchased energy is used in the production process.

Information on the CO2 footprint of firms can be combined with our economic profit data to identify which business models must change to align with the Paris Agreement. Of course, it is worth noting that the CO2 footprint alone does not indicate the capacity and the willingness of firms to green their production processes: financially weak firms have other priorities whereas highly profitable firms may not see an urge to change their business models.

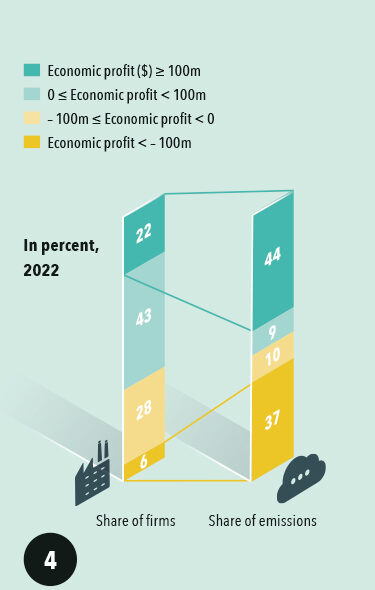

Our data suggests that there are three different groups of firms. Just 6% of firms realized economic losses over $100m in 2022, but collectively they account for 37% of CO2 emissions. This observation is consistent with the argument that financially distressed firms do not possess the means to invest in greener production processes because they first and foremost seek to stay in business.

At the other end of the spectrum, 22% of firms realized more than $100m in economic profits and accounted for 44% of CO2 emissions. These firms can invest in new production processes, but so far they may have decided against it. One explanation is that carbon prices aren’t yet high enough to warrant reducing CO2 emissions or changing the business models from which these firms extract substantial value.

This leaves a third group of firms comprising more than two-thirds of those featured in our analysis, but only accounting for 19% of CO2 emissions. They realize small economic profits or losses, which makes them particularly vulnerable to external forces that could result in cost increases such as carbon pricing schemes. Firms with high-margin pressure invest in low-carbon technology if the costs of emitting an additional tonne of CO2 warrant the investment.

For these firms, any adverse change in their cost structure matters a lot, because they are just on the brink of profitability.

The situation of the 503 firms destroying more than $100m in economic value deserves special consideration for two reasons. First, burning stakeholders’ resources will be unsustainable in the medium term. Second, it seems unlikely that these firms can mobilize enough funds to invest in green production processes. The CO2 emissions per firm in this group – 9.4m tCO2e (for comparison, the total emissions of North Macedonia amounted to 9.77m tCO2e in 2022) – are triple the size of firms in any other economic profit segment. In other words, these firms destroy financial value even though they largely externalize the environmental costs of production. If these firms’ license to operate is not to be called into question, then ways must be found to help them become greener and cleaner (accelerated depreciation could be one way to promote green investment).

Chinese firms – notable examples include GD Power Development, China National Building, Xinjiang Tianshan Cement, China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation – account for 3.1bn tCO2e (65.3% of the 4,731bn tCO2e total), US firms for 0.4bn tCO2e (8.5%), Indian firms for 0.3bn tCO2e (6.7%), and Japanese firms for 0.3bn tCO2e (6.5%) of total emissions in this economic profit segment.

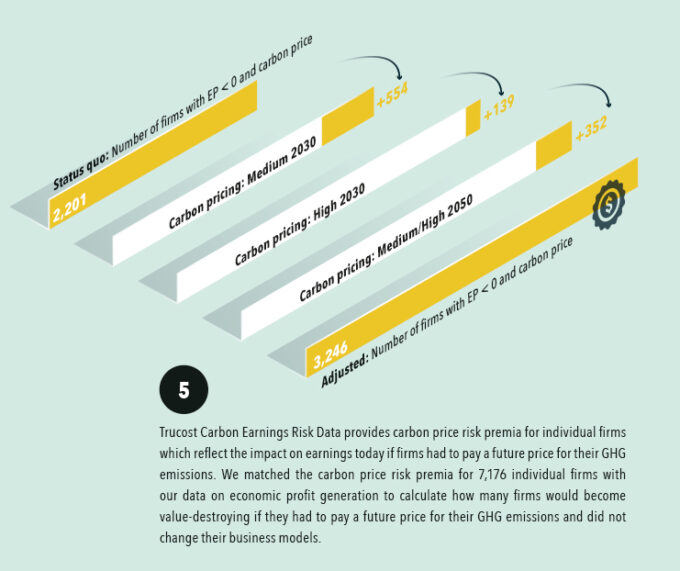

To incentivize businesses to limit their emissions and transition towards cleaner, more sustainable practices, many governments have introduced carbon prices. Carbon prices are a market-based mechanism that assigns a monetary value to the emission of CO2 and other GHGs. Since carbon prices are an additional cost driver for companies, it is crucial for owners and investors to understand how potential increases in carbon prices will affect the economic profitability of their businesses. To assess how future carbon pricing schemes may affect the ability of firms to generate economic profits, in effect, we draw on research from the International Energy Agency and the International Renewable Energy Agency. Based on their insights, S&P Trucost derived carbon price risk premia which vary by sector, geography, year, and scenario and reflect the additional financial cost paid (per metric ton of emissions) from the price that is currently paid. Three scenarios are considered:

Medium 2030: Policies will be implemented to reduce GHG emissions and limit climate change to 2°C in the long term but with action delayed in the short term.

High 2030: The implementation of policies that are considered sufficient to reduce GHG emissions in line with the goal of limiting climate change to 2°C.

2050: The implementation of policies that are considered sufficient to reduce GHG emissions in line with the Paris Agreement.

On their current trajectory with no change in business models, the number of value-destroying firms would increase by more than 1,000 (or by nearly 50%) if firms had to pay a future price for their emissions. If the 2050 carbon price was to be paid by firms today, 45% of all firms considered here would not generate economic profits. More than 500 firms would change from being value-generators to value-destroyers even if climate action was delayed beyond 2030. These findings clearly highlight the pressures for business model transformation.

If firms had to pay 2050 carbon prices on each metric ton of GHG today, an additional 11 million employees and an additional $9 trillion in assets would be stranded in firms that no longer generate economic profits. Another $150bn in tax payments by these firms would be in jeopardy. These statistics highlight the need for businesses to upgrade their production processes sooner rather than later and for governments to carefully track the effects of future carbon price hikes on corporate performance. The investments needed to switch to green business models should not be underestimated and need to be financed somehow.

Successful capitalist firms create value, which means they generate surpluses that can be deployed to a wide range of uses or that can be taxed and used to advance national and global well-being. Without the prospect of earning higher economic profits, managers and shareholders lose extrinsic motivation to take on challenging projects that can, directly or indirectly, have massive societal payoffs. Intention is not enough – just like the Good Samaritan, business must be able to fund societal improvements.

Professor of International Trade and Economic Development at the University of St. Gallen

Simon J. Evenett is currently a Professor of Economics at the University of St. Gallen and on 1 August 2024 will join the Faculty at IMD. He is also Co-Chair of the WEF’s Global Council on Trade & Investment and the Founder of the St. Gallen Endowment for Prosperity Through Trade, home of two of the leading independent monitors of how governments shape international business.

PhD candidate in international affairs and political economy at the University of St Gallen

Felix Reitz is a PhD candidate in international affairs and political economy at the University of St Gallen, Switzerland, and holds a Master’s in international political economy from the London School of Economics and Political Science. Reitz focuses on fiscal policy, international taxation, and corporate strategy under uncertainty.

26 April 2024 • by Angelica Adamski in Audio articles

Executive coach Angelica Adamski shares the challenges facing Lyndsey in aligning and leading a new and globally dispersed sales team....

23 April 2024 • by Jerry Davis in Audio articles

GenAI can deliver cost and productivity benefits for colleges and students, but there is a dark side....

Audio available

Audio available

22 April 2024 • by José Parra Moyano, Christine Legner, Konrad Schulte in Audio articles

Training and fine-tuning AI models requires troves of data, but storing and processing that data is financially and environmentally costly. Here are three ways to address the problem....

Audio available

Audio available

18 April 2024 • by Quentin Gallea in Audio articles

GenAI will allow human talent to focus on more creative, complex tasks, leading to greater job satisfaction and well-being....

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience