Almost 100 participants from all over the world part in a Discovery Event on Digital Business Transformation, where IMD Professors Donald Marchand and Michael Wade shared the latest information on organizations at different stages on the digital transformation journey, and Novartis guests Lita Sands and Achim Plueckbaum shared their experience about Novartis’s impressive digital business transformation.

Digital business transformation (DBT) is about more than devices and software. It is about organizational change through the use of digital technologies to materially improve performance. The explosion in the use of AMPS (Analytical tools and applications, Mobile tools and applications, Platforms to build shareable digital capabilities, and Social media)1 is changing the dynamics of competition in many industries. More and more companies in traditional sectors acknowledge that they need to do more about DBT, but are unclear on what steps to take. In this insights@IMD, we explore how companies can stay ahead of the game through a series of examples.

Where do you stand on the DBT journey?

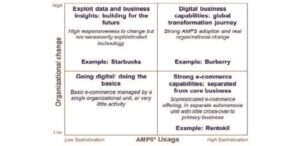

The framework in Figure 1 can help companies assess where they are. The horizontal axis represents the degree of sophistication of a company’s usage of AMPS; the vertical axis represents the scale of organizational change. The ultimate goal is to end up in the top-right quadrant. There are two paths to get there: organizational change or technological change.

A quarter of the event participants placed themselves in the bottom-left quadrant: they saw themselves as doing nothing more than the basics. Another quarter said their companies were making sophisticated use of AMPS but struggling with the accompanying organizational change; i.e. they were in the bottom-right quadrant. A handful saw themselves in the top-left quadrant; they were transforming the way they did business but struggling with the technological aspects necessary to make this change happen. Only one of the hundred or so participants claimed his company had completed the digital transformation journey. The remainder was not sure; their companies’ progress was not transparent enough for them to assess their stage on the transformation journey.

1. Organizational change led path

Burberry: From tired brand to digital powerhouse

By 2006 Burberry’s brand had lost much of its luxury brand value, and its product offerings, pricing and store design were inconsistent and outdated. To regain control, Burberry turned to digital. It hired brand and technology specialists, consolidated the brand around the two core elements of British heritage and luxury outerwear, concentrated manufacturing in Yorkshire, and decided to target a new segment: high-net-worth, emerging-market, generation-Y consumers, who were around 15 years younger than their European or North American counterparts but had little knowledge of the Burberry brand. A revised digital strategy was needed. The new CEO formed a Strategic Innovation Council to develop a new vision and a Senior Executive Council to make it happen. New VPs of social media, customer insight and mobile functions were hired to implement the new “think and speak digital” strategy.

The new management decided that digital channels were the best way to reach the new consumers. The company redesigned its website, revamped its stores and fully engaged in social media. It also rejuvenated the workforce, trained in-store staff to use digital tools such as iPads and RFID tags, and launched various online campaigns. Employees were kept informed of new initiatives through webcasts, videos and chats. A new internal platform, Burberry Chat, allowed employees, suppliers, partners and investors to link up and its use was encouraged and incentivized.

Burberry started to spend more than 60% of its marketing budget on digital media, triple the industry average. According to CEO Angela Ahrendts, “We have a Google strategy, a Facebook strategy and a YouTube Strategy. We want to reach every consumer across every one of those devices, platforms and channels.” Its Twitter, Facebook and YouTube sites attracted millions of viewers.

Starbucks: Transforming and engaging customer experience by using digital tools

Like Burberry, Starbucks was also experiencing difficulties in the mid-2000s. Sales were declining and Starbucks had to close many underperforming stores. On a digital level, the company was far behind its competitors. Store managers did not even have company email! By 2008 the company’s stock price had plunged to under $10.

Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz wanted to transform its customers’ in-store and online experience. The company created a new VP of digital ventures position and appointed Adam Brotman. This post was kept separate from other business units. CIO Stephen Gillet explained, “If I place the digital capability under engineering or IT, even with the best of intentions, it becomes heavily influenced by technology initiatives… And if I put it under a marketing function, it will inherently be dictated by a marketing campaign. We needed it to have the autonomy of its own destiny, of its own vision.”

Brotman’s first move was to offer free wi-fi in Starbucks stores, despite concerns that people would abuse the privilege. He said, “We were not doing something around wi-fi, we were doing something innovative around how we were connecting with customers.”

Starbucks successfully took the “Starbucks experience” digital, with more than 90% of all US Facebook users being either a Starbucks fan or friends with one. In 2012 the company booked $3 billion in payments via its loyalty card. Starbucks led the way in mobile payments too, processing 3 million mobile payments a week. Close engagement with customers also allowed it to collect over 50,000 innovation ideas. Today, by taking 10 seconds off every card or mobile phone transaction, it has cut customers’ time-in-line by 900,000 hours per year.

Starbucks’s DBT was led by customer insight and business change. The technological tools were relatively simple. Most of its solutions were digitally light as it used existing technologies such as wi-fi, mobile payments and social media, but it successfully integrated these technologies to improve customer engagement and operational efficiency.

2. The technology led path

Novartis: Changing the sales engagement model with customers through DBT

Aging populations, unhealthy lifestyles, emerging market opportunities and advances in science and technology offer unprecedented growth opportunities for pharmaceutical companies. Yet seizing these opportunities and creating value for customers and employees is increasingly challenging. Over the last decade, as a result of declining sales in drug products reaching maturity, Novartis was forced to repeatedly restructure the sales force and cut positions. Meanwhile the remaining sales representatives felt increasingly disengaged.

The pharmaceutical companies have historically had a unique selling model. Sales representatives performed 8-10 visits per day, communicating company priorities and drug-related information, but collected little information about the patients who used the drugs, and hardly any information was exchanged between doctors and sales reps or between reps. Novartis had no idea which drug was being sold or used or when.

David Epstein, head of Novartis’s pharmaceuticals division, wanted to change this. To achieve Novartis’s vision of being “the best pharma company” and provide “the right drug for the right patient at the right time,” he decided it was critical to reengage the sales force and customers. His vision was that sales reps should use drug info more effectively, engage doctors in meaningful conversations and increasingly deliver value-added services rather than recite static messages. His first bold move was to equip the company’s 25,000 sales representatives globally with iPads within two years.

Epstein brought two key people on board, Achim Plueckebaum and Lita Sands. Plueckebaum was recruited from his position as CIO Europe to take charge of the IT side of the project whereas Sands was recruited to take care of marketing. Despite initial challenges, the team managed to work seamlessly to push forward the technology deployment within a detailed timeline that outlined the milestones and key stakeholders in terms of key leadership events, core team direction and steering committee guidance. The deployment also integrated a new CRM rollout linked to an innovative product information presentation standard called the LaunchPad.

By using the LaunchPad standards developed specially for the Novartis iPad, sales representatives could pull any information they needed during a sales meeting – from interactive graphs to patient case studies – or call a specialist at headquarters on the spot if needed. This technology device completely changed Novartis’s selling model. Sales representatives’ lifestyle improved as sales calls were recorded on the spot, and they could do all their travel and expense reporting between doctor visits, thereby eliminating after-work administration.

The evolution of Novartis’ digital transformation moved through four phases.

Phase 1 started in 2008 with Epstein as head of the oncology unit in the pharma division. As oncology specialists moved from individual to group practices, there was a clear need to implement a more flexible cloud-based CRM system to empower the sales force to engage doctors in more meaningful discussions about Novartis products and employ sales reps’ time more efficiently with digital tools and content. In 2010 Epstein became head of the Novartis pharma division and he decided to extend the new CRM system across the division and link its implementation to the global rollout of iPads in October. By December Sands and Plueckebaum had been selected to lead the marketing and technology efforts respectively.

Phase 2 in 2011 and 2012 included Pluckebaum’s rollout of the iPads and the launch of digital product information on iPads. Novartis worked with a Toronto-based agency specialized in communicating digital content in the pharmaceutical industry to develop the information, navigation and presentation standards for adapting Novartis product information to the LaunchPad format. Sands led a major change from traditional product information campaigns launched twice yearly to an almost real-time information management environment for making digital product information useful for sales rep contacts with doctors.

Phase 3 completed Plueckebaum’s deployment of the 25,000 iPads across the global pharma sales force, while Sands continued to enable Epstein’s vision of providing truly useful digital product information for the sales reps to use. In October 2013 Sands and Plueckebaum organized a “Digital Immersion Workshop” for the 150 senior pharma division managers, during which Epstein challenged his managers to embrace the digital transformation of the division and follow the lead of companies in other industries that had changed their business models with a new mix of digital and non-digital assets and capabilities. The workshop focused on three key themes: customer centricity, market making and digital culture at Novartis.

Phase 4 in 2014 is now leading to new understanding on integrating digital into the pharma business strategy and pharma senior executive decision-making. It has also led to a renewed engagement of the sales force across the world with improved customer interactions, higher morale and better daily productivity for the sales reps. Most significantly, the digital transformation is now changing the operating culture of the division globally as well as the integration around more useful customer and product information and analytics to improve customer engagement.

Digital as a tool to drive strategic organizational renewal

Having a sophisticated digital presence is a means to an end, not an end itself. It is an enabler of business benefits such as higher revenues, greater efficiency and enhanced innovation. Organizations in the top-right quadrant of Figure 1 achieve these benefits much more easily than those in other quadrants. DBT requires technology change, represented today by a sophisticated use of AMPS technologies, and organizational change. Both are necessary and neither is simple.

The kind of organizational change pursued by Burberry and Starbucks challenges the status quo. It requires strong leadership and vision to see the threat of disruption and push through the inevitable resistance. Further, a short-term hit is often needed to achieve a longer-term gain. Both Burberry and Starbucks saw their results fall at the outset of their digitization journey, before they began to rise again.

Technological change is also challenging. AMPS technologies require new skills and technologies and often large capital expenditures. The Novartis journey required the development of new systems and competences, some of which were at odds with the organization’s prevailing culture and functional practices in IT and marketing. New technologies such as iPads led the transformation, but the management and sales culture as well as new organizational systems and processes had to follow.

Organizations should conduct a self-assessment to determine which quadrant they are in and then develop a strategy to make the necessary organizational and technological changes to successfully navigate the DBT journey.

Discovery Events are exclusively available to members of IMD’s Corporate Learning Network. To find out more, go to www.imd.org/cln