How to harness the power of nonmarket strategy

Forward-thinking leaders proactively shape their external environment, turn uncertainty into certainty, and create substantial value in the process....

Audio available

by Stefan Michel Published April 9, 2024 in Strategy • 2 min read

Daniel Kahneman, who passed away last month, and his late collaborator Amos Tversky established what’s now known as behavioral economics. The two researchers started to challenge the foundations of economics – which assumes that humans are rational decision-makers, the so-called “Homo economicus” – more than 50 years ago.

Psychology professor Robert Cialdini admired Kahneman for “being always willing to go where the research evidence took him, even when it contradicted exalted knowledge paradigms, such as classical economic theory, and, even more impressively, when it contradicted his own prior assertions, such as certain conclusions within his best-selling book Thinking, Fast and Slow.”

One of the many research experiments Kahneman and Tversky conducted related to the anchoring effect. This describes a cognitive bias when people must estimate a certain quantity, such as the price of a product or the number of countries in Africa that are members of the UN. People will estimate that number based on numbers that are available to them at that moment. Those reference numbers serve as anchors, even if they are irrelevant to the question.

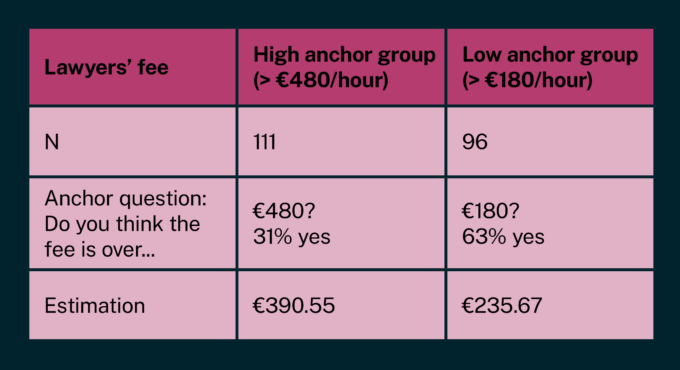

This principle is often applied to pricing psychology. I have tested the anchoring effect with IMD participants multiple times to demonstrate how, to use the famous book title by Dan Ariely, “predictably irrational” we are.

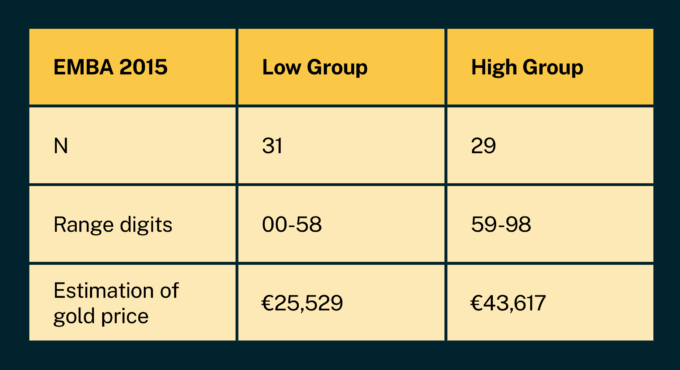

In one experiment, I asked the 2015 IMD EMBA class to write down the last two digits of the phone number they use most often. Then, I asked them to estimate the average price for one kilogram of gold in Euros without looking it up online.

I split the 60 participants into two groups. Members of the first group indicated a phone number with the last digit being lower than 58, and the second group with a higher number.

This phone number served as an anchor.

When calculating the average estimation for the price of a kilogram of gold, the first group was at €25,529, while the second group estimated a price of €43,617, an increase of 71%.

While the anchoring effect would suggest a positive correlation between the anchor (the phone number) and the estimation, the effect seemed to be very large. Consequently, I did what researchers are supposed to do and replicated the experiment with the IMD EMBA class of 2016. Here, we had fewer students and a lower, yet remarkable increase of 31% from €28,482 to €37,242.

And that’s precisely how anchoring works in pricing psychology. An initial piece of information (the anchor) disproportionately influences our estimate of a subsequent unknown quantity.

Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 thinking, explained in Thinking, Fast and Slow, can help explain why this happens.

System 1: This is our fast, automatic thinking. It’s efficient but prone to biases. When encountering an anchoring situation, System 1 quickly grabs the initial number (the anchor) and uses it as a starting point for our estimate.

System 2: This is our slow, deliberate thinking. It’s more logical and analytical but requires effort. Ideally, System 2 should take the initial anchor provided by System 1 and critically evaluate it before forming a final estimate.

However, in anchoring situations, System 2 often defaults to accepting the anchor without sufficient adjustment. This can happen for a few reasons:

“Finally, a growth mindset always starts with the personal humility of admitting that we don’t know.”

The conclusion for setting prices is straightforward: put the anchor high. You may attract customers with a low price to your store or website. But once they are in the decision process, show them the best model you have available, or at least don’t start with the cheapest offer first. For example, I am still surprised by how many restaurant owners list their wines by price range, starting with the cheapest.

I do not suggest that you create moon prices or try to manipulate consumers. Showing the best offer first, the most advanced model, the fastest bike, and the safest car seat is fair practice. At the same time, be aware that the anchoring effect is just one of many biases influencing the decision process.

There are many things we can learn from Kahneman. First, understanding that humans think fast and slow by combining System 1 and System 2, which helps us to make better decisions. More importantly, it helps us to understand others’ decisions better. The many biases that Kahneman researched, such as the anchoring effect, prospect theory, or dual entitlement, are useful in many everyday situations. Finally, a growth mindset always starts with the personal humility of admitting that we don’t know. In Kahneman’s words: “We are blind to our blindness. We have very little idea of how little we know. We’re not designed to know how little we know.”

The anchoring effect is just one of many human biases and tendencies that you can leverage to your advantage – if you are aware of them.

When costs rise, what should you do to preserve your profit margin? Putting your prices up may not be the answer. Let’s assume a B2B supplier offers a product for $100 per unit and wants to increase the price by 8%. Psychologically, the buyer perceives this as a loss and might react negatively. As we know from the “loss aversion” theory, customers count losses much more heavily than gains.

Consider how to give customer satisfaction while also making sure your bottom line doesn’t suffer. For example, give them:

Learn more about the psychology of pricing in Michel’s book Real-Impact Marketing.

Professor of Management and Dean of Faculty and Research

Professor Stefan Michel‘s primary research interests are AI’s impact on strategy, pricing, and customer-centricity. He has written 13 books, numerous award-winning articles and ranks among the top 40 bestselling case study authors worldwide by The Case Centre. He is currently Dean of Faculty and Research at IMD and is also Program Director for two IMD programs: the 10-day Breakthrough Program for Senior Executives (BPSE), guiding leaders in defining their next breakthrough; and Strategic Thinking, an 8-week online program with 1-1 coaching, helping professionals become better strategists while working on a concrete strategic initiative for their organizations.

June 26, 2025 • by Michael Yaziji in Strategy

Forward-thinking leaders proactively shape their external environment, turn uncertainty into certainty, and create substantial value in the process....

Audio available

Audio available

June 4, 2025 • by Stéphane J. G. Girod, David Branch in Strategy

The traditional e-commerce model is on its last legs. In a disrupted luxury landscape, brand leaders are shifting focus to unified commerce, hyper-personalization, and deeper digital storytelling to completely reinvent the customer...

June 3, 2025 • by Anna Cajot in Strategy

Donald Trump’s tariff tactics offer a bold case study in game theory in negotiations. By setting the rules early, limiting options, and projecting power through credible threats, his approach shows how negotiations...

May 27, 2025 • by Robert Earle, Karl Schmedders in Strategy

With solar power flooding grids, the duck curve creates both challenges and opportunities for businesses. Learn how smart companies can harness this shift to cut costs and boost efficiency....

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience