Inside the ‘gray zone’: how to lead when no one is right

Effectively integrating ethics, values, and diversity is vital for responsible leadership. Here is a guide to decision-making in the 'gray-zone'. ...

by Michael D. Watkins Published 4 October 2022 in Leadership • 7 min read

Drought and floods, war in Ukraine, rising political polarization, severe economic headwinds, and an escalating great power conflict have made the dire challenges we face all too clear. Perhaps never has there been a time when leadership development has been more critical. If we are to avoid a future of famine, fragmentation and futility, the best hope we have is to develop the right kinds of leaders – and lots of them. We must undertake this work to ensure the survival of our societies and perhaps even our species.

Two dangerous beliefs around leadership must first be debunked if we are to weather what is to come. The first is the assumption that history passes through cycles of good times and bad times, through golden ages and dark ages. The idea that good times come and go and that “this too shall pass” retains currency and so is deceptive and dangerous because it can breed complacency. For we may be facing a coming of the worst of times. Not a smooth flow through a cycle but a catastrophic rupture that changes everything.

While the leaders we need to overcome the challenges we face may indeed ‘just show up’ as events unfold, what if they don’t or don’t in time to make a difference?

The second belief is that the “times make the leaders”. This implies that great leaders emerge fully formed in hard times, possessing the qualities required to steer through stormy waters. It seems true that hard times can call forth extraordinary leaders. Take President Volodymyr Zelensky who, but for the challenge of mobilizing the Ukrainian people to oppose Russian aggression, would have been a historical footnote. Now his example of great leadership will ring down through the ages. While the leaders we need to overcome the challenges we face may indeed “just show up” as events unfold, what if they don’t or don’t in time to make a difference?

Given our unprecedented challenges, I believe we cannot afford to just wait and hope. We must mobilize collectively and rapidly to develop leaders – many of them – who are prepared to deal with the crises to come, much as the military builds reserve forces that can be called up in wartime.

So how can we go about recruiting and developing the young leaders ready to lead through emerging crises? Having studied political and military leaders during major wars, I came away believing we need to engage in two fundamental tasks: one, seeking potential leaders with certain qualities, and two, helping them develop specific skills.

By “qualities”, I mean in-built aspects of temperament-shaped experience, in addition to a baseline level of raw intelligence, that consistently show up in successful wartime leaders. The specific character traits we should seek rest in the ability to balance opposing tensions, known as “leadership polarities.” As described in Andrew Roberts’s in-depth study, Leadership in War, polarity management is evident in the leadership of Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt during the Second World War, and Abraham Lincoln a century earlier.

Great leaders have both self-confidence and humility. There is no doubt that leaders must be confident, and it helps to have intelligence, charisma, and the work ethic to get things done. But one trait, often overlooked, that successful leaders have is humility. A humble leader will recognize their strengths and weaknesses and acknowledge their blind spots. This means they will be open to learning and willing to show vulnerability – a trait that will make them appear more approachable to their staff. They also bring compassion to their leadership and allow their teams to make mistakes and learn from them.

Senior executives spend their days juggling multiple tasks and strategic priorities. But there are times when dealing with critical issues that they will need to focus on a singular issue. This enables the brain to enter the flow state, reducing distractions and increasing productivity.

Leaders need tremendous energy to motivate their teams, set the direction and inspire others to think out-of-the-box. At the same time, leadership requires self-control. The most successful leaders will tame their natural inclination to micromanage and focus on the most important tasks. It’s essential to remain focused on the big picture and ignore minor distractions.

Leaders must sometimes make very hard, even life-and-death, choices. But they also know when to demonstrate compassion and employ empathy to motivate people. This can be a tricky balance to achieve, but it is an essential skill, particularly in times of crisis.

Leaders must make rapid decisions in a crisis without having all the necessary information available. Strong leaders also get ahead of changing circumstances and will seize the initiative rather than wait for the situation to deteriorate. At the same time, they know when it is best to wait and let a situation ripen, being ready to react decisively when it does.

Innovation is crucial to create competitive advantage, but successful imitation can also be a way to gain a strategic edge. The skill is knowing when to pursue a truly innovative approach and when imitation will suffice.

One key pillar of finding future leaders will be screening for qualities in the form of the ability to manage these sorts of polarities. We need better assessments to help us do this, focusing on evaluating polarity-management capabilities.

The second pillar is the development of specific leadership skills. There has been a long and continuing debate on the question of what leadership is. In his 1974 Handbook of Leadership, Ralph Stogdill, a Professor Emeritus of Management Science and Psychology at Ohio State University, noted that “there are almost as many different definitions of leadership as there are persons who have attempted to define the concept”.

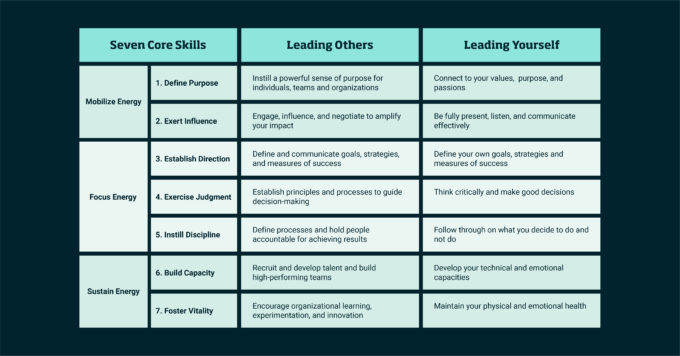

At the risk of adding to the confusion, I have developed “seven core leadership skills” and explored them during my work with senior executives with substantial success.

The starting point for developing leaders is recognizing that leadership is all about energy. The work of leadership is to mobilize and focus the potential energy of people, teams, and organizations to achieve desired goals on a sustainable basis

Mobilization means identifying and activating potential energy sources; for example, by articulating a compelling vision or fostering a sense of shared purpose that motivates.

Focus requires directing the energy that you mobilized to achieve the needed work; for example, by defining strategies, setting goals, and driving accountability.

Sustaining means replenishing existing energy sources and developing new capabilities that increase efficiency and impact. This can be the toughest dimension of leadership: supporting your people through challenging times. Returning to the example of Zelensky, he has done an incredible job in mobilizing his people and has developed a clear war strategy. The hard part will be sustaining the energy of his people.

Now leaders can’t hope to mobilize, focus, and sustain the energy of others if they can’t mobilize, focus, and maintain their own energy on a sustainable basis. Doing so requires helping those young leaders to build the right “inner leader” capabilities, develop the right practices, and foster personal resilience.

The table (above) should not be read as a definitive leadership model, but rather as a way to guide the work of developing the leaders we need.

In conclusion, we face times of unprecedented peril. Other than sound policies and technological progress, leadership is what will see us through. We must identify potential leaders drawn from all types of organizations with the inherent ability to manage polarities and help them to develop essential leadership capabilities that they need to mobilize, focus, and sustain energy. Given the accelerating crisis, this is work we must pursue with urgency and determination.

Professor of Leadership and Organizational Change at IMD

Michael D Watkins is Professor of Leadership and Organizational Change at IMD, and author of The First 90 Days, Master Your Next Move, Predictable Surprises, and 12 other books on leadership and negotiation. His book, The Six Disciplines of Strategic Thinking, explores how executives can learn to think strategically and lead their organizations into the future. A Thinkers 50-ranked management influencer and recognized expert in his field, his work features in HBR Guides and HBR’s 10 Must Reads on leadership, teams, strategic initiatives, and new managers. Over the past 20 years, he has used his First 90 Days® methodology to help leaders make successful transitions, both in his teaching at IMD, INSEAD, and Harvard Business School, where he gained his PhD in decision sciences, as well as through his private consultancy practice Genesis Advisers. At IMD, he directs the First 90 Days open program for leaders taking on challenging new roles and co-directs the Transition to Business Leadership (TBL) executive program for future enterprise leaders, as well as the Program for Executive Development.

12 hours ago • by Jennifer Jordan in Leadership

Effectively integrating ethics, values, and diversity is vital for responsible leadership. Here is a guide to decision-making in the 'gray-zone'. ...

5 December 2024 • by Jean-Claude Gallet in Leadership

How quick thinking, strategic choices, and trust in the team kept one of the world’s most iconic landmarks from destruction – lessons every leader can apply in times of crisis. ...

27 November 2024 • by John R. Weeks, Francesca Giulia Mereu in Leadership

Typically, negative experiences hit with about four times the force of positive experiences. Critical feedback hits most of us harder than reinforcing feedback. Here we consider three mysteries of negativity bias and...

22 November 2024 • by Ada Tsang in Leadership

Ada Tsang became the fastest woman to climb Mount Everest, beating the previous record. She shares her powerful learnings. ...

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience