How the digital highway code aims to curb internet violations

UNESCO guidelines for the governance of digital platforms offer lessons for more effective collaboration between companies, civil society, and governments....

Audio available

by Michael Yaziji Published 11 October 2023 in Governance • 5 min read

Business decisions are rarely easy, but it’s fair to say the trade-offs facing company executives today are extraordinary, particularly as they adopt and espouse missions that include the interests of a broad range of stakeholders. In so doing, they create internal and external expectations that may, at worst, be incompatible and, at best, be incommensurate.

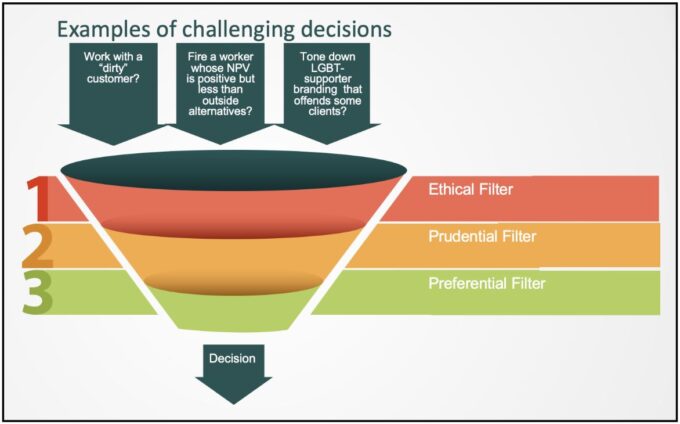

Consider three examples that companies I work with have recently faced.

A professional services firm, with stated organizational goals of improving the climate, that is asked to help an energy company (85% fossil fuel production) improve their competitive position. Should it engage?

An executive with a long-term team member aged 62 who is doing an OK job but, if replaced by an outsider, overall organizational performance would improve. Should she be replaced?

A global firm that espouses diversity and inclusion, including publicly supporting LGBTQ month, risks losing business from clients in countries with different values.

There are no easy answers to these cases. And sometimes details matter. But in many cases, the multi-dimensionality of the decision can make executives throw up their hands in exasperation.

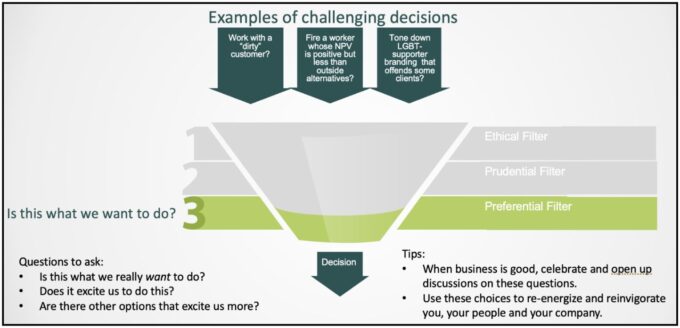

I have developed a simple framework to help crystallize your thinking around decisions that span financial, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues. The framework consists of three filters: ethical, prudential, and preferential, helping leaders to adhere to moral principles, as well as avoid risks and consider the best options as they make complex decisions. Executives can gain conceptual clarity by decomposing decisions through these three filters. If a choice successfully makes it through all three filters, they should pursue that option.

Ethics is a notoriously complicated issue. Different ethical approaches — virtue, rights-based, care, and consequentialist — give expression to different, and often conflicting, aspects of our moral intuitions.

Referencing the three cases above: how do we measure the long-term global consequences for engaging with a “dirty” client? Do we owe loyalty to the moderately productive long-term employee? When should we stand up for the rights of others, and at what cost to ourselves?

Nonetheless, executive teams should discuss these different ethical approaches and check their own moral intuition. They may find that there are “red lines” the company won’t cross. During the ethical filter phase, it is important to stay focused on the ethics, not on the bottom line. Asking these hard questions will, ultimately, ensure that ethical issues are embedded in your thinking.

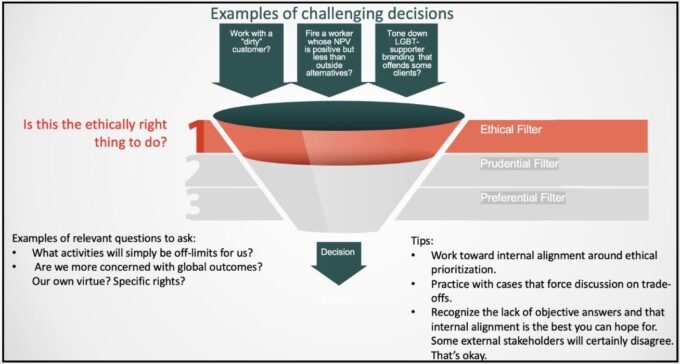

The prudential filter uncovers the short and long-term self-interest for firms weighing up difficult calls. In doing so, companies can determine if a particular course of action is in their interests.

Compared to ethical considerations, executives are used to evaluating options in terms of what is in the interests of the firm. Questions of direct and indirect financial impact, brand and strategic alignment, as well as risk profile, are all part of the familiar mix.

Though the dimensions of prudence are more familiar, as any experienced executive will attest, determining the answers to these questions is often a question of art, intuition, and experience, as much as data and objective assessment.

Returning to our exemplary cases, working with a fossil-fuel company will directly benefit our bottom line, but will we lose market credibility in our efforts at branding ourselves as a sustainable organization? Just how much damage will be done to remaining employees’ engagement if we replace a mediocre employee? And if we don’t tone down our LGBTQ-supporter position, just how much will it really impact our bottom line?

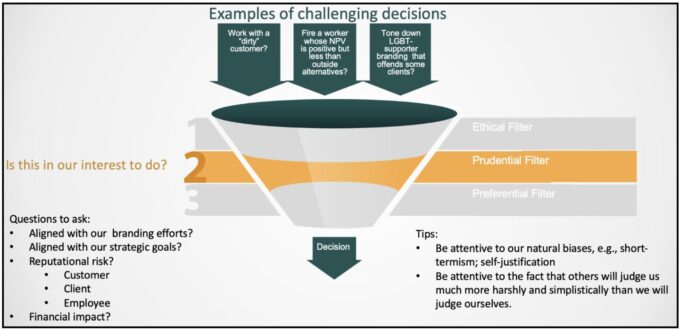

The first two filters might be understood as more negative or exclusionary because the intent is really to determine which options should be excluded for ethical or prudential reasons. By contrast, the final filter of preference is a bit more positive and inspirational.

Often, when times are tough, we rarely have much choice when making it through the first two filters. As a result, we might be left with choices that feel like an obligation and work.

If business is going well, we might have quite a few options that pass through the first two filters, more than we can actively pursue. In this happy state, we have room to ask ourselves questions such as: will this choice open up fulfilling new avenues and be truer to our mission? Is this client one that we really want to work with? Does it inspire and give meaning to our work? Are there other options that excite us more?

These filters are not a simple recipe or algorithm, where you stick in choices at one end and come out with clear decisions on the other. The filters do not eliminate gray areas, uncertainties, and trade-offs. Those are inherent to leading in the real world. Nonetheless, by consciously applying the three filters to the multidimensional choices that leaders regularly face, they can decompose different aspects of the choice and manage each with greater clarity. This, itself, is a gift.

Michael Yaziji is an award-winning author whose work spans leadership and strategy. He is recognized as a world-leading expert on non-market strategy and NGO-corporate relations and has a particular interest in ethical questions facing business leaders. His research includes the world’s largest survey on psychological drivers, psychological safety, and organizational performance and explores how human biases and self-deception can impact decision making and how they can be mitigated.

8 May 2024 • by Tawfik Jelassi in Governance

UNESCO guidelines for the governance of digital platforms offer lessons for more effective collaboration between companies, civil society, and governments....

Audio available

Audio available

9 April 2024 in Governance

When the going gets tough, the behavior and decisions of board members can heavily influence the fate of companies and have far-reaching repercussions. When the going gets tough, the behavior...

Audio available

Audio available

26 January 2024 • by Hischam El-Agamy in Governance

Though they may find it an invaluable tool, scenario planning isn’t just for business leaders. It has also been successfully used in brokering peace between conflicting sides. This is why it should...

25 January 2024 • by Siri Terjesen in Governance

As companies grapple with economic uncertainties, the progress towards more inclusive boards is slowing down. Broadening the talent search and investing in training programs are crucial for redressing the slide....

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience