“Who the hell are YTL?”

This was the headline in Britain’s Daily Telegraph newspaper after Malaysian infrastructure conglomerate YTL successfully won a bidding war to take control of Wessex Water for £1.2bn ($1.47bn) in 2002.

The headline – and the unfounded allegations of bribery in the bidding process – underscore how firms perceived as outsiders face significant stigma when trying to gain a foothold internationally. Lacking status in the eyes of a new audience, they may be viewed with suspicion, particularly if they are involved in something as economically and socially sensitive as an infrastructure project, where the cost of things going wrong is high.

Many scholars regard organizational status as an intangible asset. Yet what has become clear from previous studies is that firms often struggle to transfer their high domestic status across borders, and this is especially true for family firms from emerging markets trying to gain a foothold in a developed market where they are perceived as a “nobody from a faraway land”. This is because status often depends on how visible and familiar an organization is to the target audience.

So how can family businesses entering a new market accumulate status? And are there any ways they can overcome the liability of being labeled a low-class outsider? A prime example is Malaysian firm YTL, which has grown into a highly trusted multinational property and utility conglomerate.

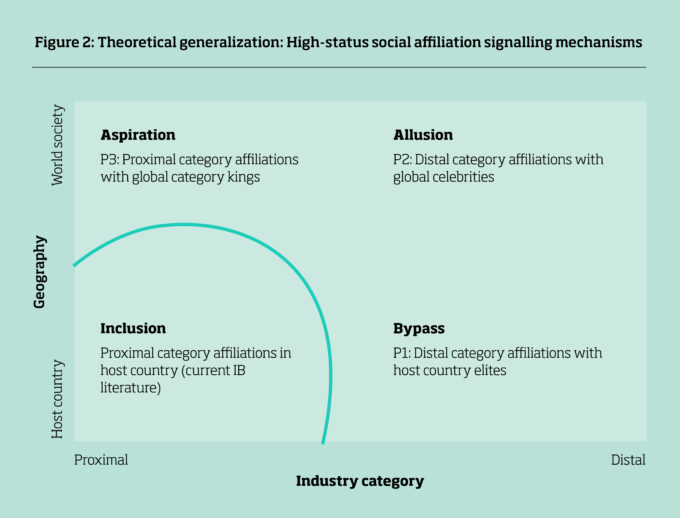

With my colleague Michael Carney from Concordia University, we explored how, when audiences have no information about a newcomer, they assign status based on with whom the newcomer affiliates. Could this also apply to family businesses from emerging markets, and, if so, could this insight be used by family businesses to facilitate their internationalization?We analyzed the firm’s annual reports from 1986 to 2019 to examine how the family conglomerate was representing itself. Specifically, we looked at the photos in these reports to analyze which people YTL leaders affiliated with over time. We suspected these choices might serve a purpose: signaling who your friends are to provide status clues to new audiences. After all, if people don’t know who you are, they look at who you know.

Founded in 1955 by Yeoh Tiong Lay, whose initials gave the firm its name, YTL started as a construction company before diversifying into real estate development, hotel operations, and utilities, becoming a well-known domestic player. From 1990, it started to expand internationally, first in emerging markets and later in developed countries.

During the 34 years of annual reports available for analysis, we found a total of 452 images depicting 520 unique non-YTL individuals and 56 YTL representatives. We analyzed the individuals’ names and positions depicted in the photos and distinguished them into three broad categories: business, government, and civil society. Second, we coded their nationality into three categories: home country, host country, and other countries. Third, we studied the photo’s intended narrative by considering details such as context, venue, dress code, and spatial clues.

Common wisdom is that the only way to become an insider in an overseas market is to create your business networks there, which takes a lot of time and effort. From our findings, however, we discovered that this is not the only approach. We outline three status-signaling mechanisms that are far less resource intensive.