How the digital highway code aims to curb internet violations

UNESCO guidelines for the governance of digital platforms offer lessons for more effective collaboration between companies, civil society, and governments....

Audio available

by Richard Baldwin, Simon J. Evenett, Fernando Martín Espejo Published 30 December 2023 in 2024 trends • 8 min read

What will 2024 bring for you and your business? IMD faculty and other experts offer their predictions for the year ahead.

What will 2024 bring for you and your business? IMD faculty and other experts offer their predictions for the year ahead.

It’s been a rocky year for global trade. The World Trade Organization now expects trade in world merchandise to have grown just 0.8% in 2023, less than half of the 1.7% growth it forecasted earlier in the year, buffeted by rising inflation, high interest rates, and simmering geopolitical tensions.

What’s in store for 2024? Can we expect more of the same? Or will the situation start to stabilize? Our experts share their insights on what to watch out for over the next 12 months.

Globalization is under fire in many nations, no doubt about it. International commerce – and indeed the whole idea of economic openness – has been challenged by a long series of massive shocks ranging from Brexit and President Trump’s tariffs to the pandemic, the Russo-Ukrainian war, battles in the Levant, and rising geoeconomic tensions.

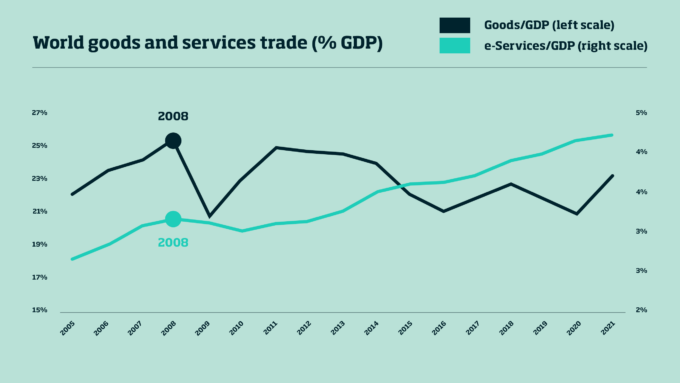

Newsfeeds are filled with headlines about de-globalization and the adoption of inward-oriented trade and industrial policies. But the headlines can be deceiving. The facts are that global trade in goods – as a share of global income – has recovered from COVID-19 lows, even if it has not reversed its downward trend (Figure 1). Digitally enabled trade in services, by contrast, never faltered, even in the depths of the pandemic, and continues to power ahead. As we head into 2024, my research suggests that trade in goods will continue to stagnate while trade in digitally enabled services (e-services) will continue to boom.

The US and China are now strategic rivals in the economic, political, cultural, and military spheres. But neither wants this intense competition to lead to WWIII. The US is actively trying to prevent China from acquiring technology that would counter the US’s military edge and promoting the diversification and de-risking of the American supply. This involves encouraging more production in the United States while hindering production in China of a narrow range of goods, most notably including the highest-end semiconductors, technology related to quantum computing, and advanced AI that has military and surveillance uses. Apart from these goods, the Biden administration is not pursuing policies aimed at hindering China’s economic prosperity.

China’s retaliation to date has been very measured – limited to requiring export licenses for a few inputs that are critical to semiconductor production (gallium, germanium, and graphite). These are best seen as a ‘shot across the bow’ of the US restrictions aimed at preventing China from developing the capacity to produce or purchase the very highest-end semiconductors.

Both sides are trying to cool down the conflict. As one White House official put it, “The United States and China are in an intense competition, and we believe the best way to manage that competition is through equally intense diplomacy.” Biden and Xi met for the first time in about a year on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit in November 2023, sending a signal that they are committed to working out how to cooperate where they can. I hedge my conjecture with a famous Lenin quote, “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” Great power rivalries are usually stable but beware that things can go south quickly.

Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and climate-related disruptions will increasingly impact international business and international trade globally. What’s more, the interconnectedness of global trade will only amplify the risks of climate-related disruption. Some extreme weather events disrupt production directly via droughts, floods, or overheating of workers. Others – such as low water levels in the Rhine, or hurricanes that damage ports – disrupt international transportation directly.

“With machine translation being so good, and getting better so fast, English speakers will soon find themselves in much more direct competition with the billions of service workers who don’t speak English.”

How do we know that extreme weather is becoming more common due to climate change? Nothing is certain in the business of climate change, but there are many hints that the unusual weather the world has seen in recent years is not a fluke. These clues include record-breaking heatwaves on land and sea and in most parts of the planet, severe floods and droughts, and extreme wildfires. To withstand the challenges of extreme weather events, policymakers, and business leaders will need to work together to build more resilient and adaptable systems.

Microsoft recently launched speech translation technology that allows participants in a Teams meeting to see live captions of the conversions that are translated into a language of their choice. This is a big deal. There is even a story in the Old Testament suggesting that language-linked divisiveness was divinely inspired. The book of Genesis discusses a building that humans were constructing to reach the heavens: “The Lord said, ‘If as one people speaking the same language, they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other.’” The structure came to be known as the Tower of Babel, where “babel” means a confused noise made by a number of voices.

Not to put too fine an edge on it, simultaneous speech translation is dismantling the Tower of Babel. English speakers – who have long had an edge when it comes to international commerce, especially trade in services – are in for some competition. With machine translation being so good, and getting better so fast, English speakers will soon find themselves in much more direct competition with the billions of service workers who don’t speak English. Machine translation won’t let them speak perfectly but perhaps well enough to participate in remote office work. The result will be a tsunami of global talent in the online service sectors. This will increase the choices facing employers or remote workers, generate more opportunities for high-skill low-wage workers in emerging markets, and create a lot more competition for advanced economy workers who have jobs that can be done remotely.

Nearly two billion people living in some of the most important economies on Earth will vote next year in elections. The run-up to polling day doesn’t normally make for enlightened trade policies because plenty of opportunistic politicians will try to blame foreigners for their own countries’ deficiencies. Already governments are maneuvering to deliver short-term political highs by whacking trading partners. The European Commission’s investigation into fast-growing imports of electric vehicles from China is cynically timed to deliver a verdict just before the elections to the European Parliament. Few US politicians will resist the siren call of being tough on Chinese trade and investment as November 2024’s American elections approach. Furthermore, so tight is that US election that the Biden Administration’s patience with the EU on steel will likely snap, leading to transatlantic trade tensions in 2024.

With geopolitical tension top of many executives’ minds, security of supply considerations will remain an important narrative for many governments and corporate buyers during 2024. Will Russia again tighten the screws on grain exports from Ukraine? Will China retaliate against harsher US trade and investment measures by curbing exports of the so-called ‘rare earth’ minerals, critical to the production of many IT products? Derisking pressures – a term used by many to signal reduced dependence on China and other geopolitical foes – won’t go away.

Furthermore, should events in Gaza spiral out of control, some petrol Arab states may find it impossible to resist national pressures to impose oil embargoes. These are unlikely to cause the same damage as witnessed during the 1970s. Even so, oil price hikes are the last thing most economies need as their central banks get inflation under control.

A number of slow-burn trade policy pressures will come to the fore during 2024. October 2023 saw the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) come into effect. This scheme will impose additional taxes on imports from outside the EU that cannot show they have paid enough charges for the carbon generated during a good’s production. Importers will start receiving their first CBAM bills early in 2024 and there will inevitably be harsh words about EU implementation practices. Some nations may take the EU to court at the World Trade Organization. Others may just retaliate straight away by jacking up trade barriers on EU exports and argue that it is better to negotiate with Brussels from a position of strength. Expect headline-grabbing standoffs over carbon taxes. Other sore points include the EU’s regulations on sourcing products from areas with extensive deforestation and plans in the works to impose extensive regulation on cross-border supply chains operating into and out of the European Union.

Despite these concerns, the much-feared split of the world economy into separate trading blocs is unlikely to happen during 2024. The most likely trigger would be an outrage perpetrated by either China or the United States. To many Western governments, any attempt by China to invade Taiwan would be a step too far and would likely result in harsh economic sanctions on Beijing. Yet those American military experts who claim to track this matter aren’t publicly warning that this outcome is likely in 2024. Schism isn’t impossible in 2024, just very, very unlikely.

Against this gloomy backdrop are some positive trends that will keep creating opportunities for forward-looking businesses. Africa is pushing ahead with implementing a massive continental free trade agreement, strengthening ties between nations likely to see the fastest population growth through to 2050. Plus, by and large, the sourness expressed across the Atlantic towards globalization and trade finds no counterpart across the Asia-Pacific region. The mistake here is to let zero-sum narratives in the West dominate senior executive decision-making. After a divisive election season in 2024, some may conclude that the derisking needed involves limiting exposure to slower-growth, surly Western economies.

Professor of International Economics at IMD

Richard Baldwin is Professor of International Economics at IMD and Editor-in-Chief of VoxEU.org since he founded it in June 2007. He was President/Director of CEPR (2014-2018), a visiting professor at many universities, including MIT, Oxford, and EPFL, and a long-time professor of international economics at the Graduate Institute in Geneva. Richard is an expert in global economic policy and theory, specializing in international trade.

Professor of International Trade and Economic Development at the University of St. Gallen

Simon J. Evenett is currently a Professor of Economics at the University of St. Gallen and on 1 August 2024 will join the Faculty at IMD. He is also Co-Chair of the WEF’s Global Council on Trade & Investment and the Founder of the St. Gallen Endowment for Prosperity Through Trade, home of two of the leading independent monitors of how governments shape international business.

Head of the the Analytics Unit at the Global Trade Alert

Fernando Martín leads the Analytics Unit at the Global Trade Alert. His work focuses on trade and industrial policy with a special focus on geopolitics and geoeconomics. He holds a PhD in business economics from KU Leuven and an MSc in political economy of Europe from the London School of Economics and Political Science.

8 May 2024 • by Tawfik Jelassi in Governance

UNESCO guidelines for the governance of digital platforms offer lessons for more effective collaboration between companies, civil society, and governments....

Audio available

Audio available

9 April 2024 in Governance

When the going gets tough, the behavior and decisions of board members can heavily influence the fate of companies and have far-reaching repercussions. When the going gets tough, the behavior...

Audio available

Audio available

26 January 2024 • by Hischam El-Agamy in Governance

Though they may find it an invaluable tool, scenario planning isn’t just for business leaders. It has also been successfully used in brokering peace between conflicting sides. This is why it should...

25 January 2024 • by Siri Terjesen in Governance

As companies grapple with economic uncertainties, the progress towards more inclusive boards is slowing down. Broadening the talent search and investing in training programs are crucial for redressing the slide....

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience