Digital sustainability: it pays to be a leader, not a laggard

Companies that excel in both digital and sustainable transformation attract a stock market premium, according to research. So, how do you tap into that value? ...

by Alfredo De Massis, Ivan Miroshnychenko Published 6 December 2022 in Sustainability • 7 min read

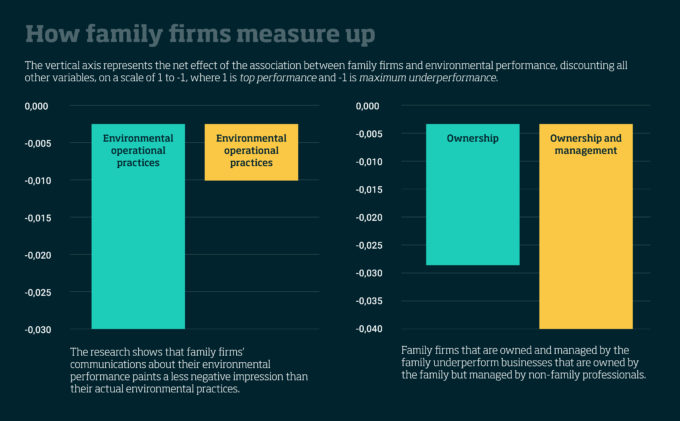

In a study that drew on data from firms for the 12-year period from 2009-20, we unearthed a striking finding: family businesses, on average, fare slightly worse than other types of firms when it comes to environmental performance.

In particular, our research showed that companies owned and run by the family tended to display the weakest environmental credentials, whereas companies that are owned by the family but run by non-family professionals leaned towards better environmental performance.

Our findings challenge the long-held perception that family businesses, because of their traditional focus on longevity and stewardship, tend to be more socially and environmentally responsible than non-family enterprises. Our research underlines the need for families to understand why this underperformance might be happening in order to establish greener business practices.

If such businesses weren’t important, the relatively small difference in environmental performance – the quality of their environmental operational practices and how they communicate them – compared with other types of business might not matter.

However, family-controlled entities account for at least two thirds of all businesses globally, and in the world’s biggest economies – Europe and the US – their share is even higher at 70%. Though many of these are so-called mom-and-pop firms, their ranks include giants such as Walmart and Cargill in the US, Volkswagen in Germany, Fiat in Italy, Tata in India, and all of Hong Kong’s property-based conglomerates.

No single factor explains the overall sub-par performance of family firms. Rather, it appears to stem from a congruence of factors, starting with the fact many of the classic features that define family businesses can affect companies both positively and negatively.

These features are often related to the availability of resources and talent, how the next generation is integrated, and how much control (and the nature of it) the family wields over the governance and day-to-day operations of the company.

One common factor is generational, with younger family members tending to want to take action on green issues more than older ones, who often hold the reins of power. This can lead to family tension and disagreements that can hamper the decisions, changes, and investments necessary to drive greener business practices. Conflicts within a family and the ineffective onboarding of young family talent often result in a firm being unable to move beyond its core competency to embrace new challenges.

Many family firms want to take action on the environment, but struggle to implement the necessary measures due to the complexities of family decision-making processes, constraints related to how resources are deployed, and how talent with the right expertise is sourced and used.

Family businesses, especially those with fewer non-family skilled professionals and an over-reliance on a few decision makers, may also struggle more than other types of businesses to cope with the increased complexity of environmental regulations and the way they differ across borders.

In addition to the challenges posed by these classic internal dynamics, we see two types of family business emerging from our research: agents and stewards.

Families that adopt a stewardship approach follow the archetype of family enterprises that favor longevity and stability over short-term profits to create a legacy for future generations. This can mean putting an emphasis on areas such as building good relationships with employees, communities, suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders, which in turn can lead to aspirations to be more environmentally responsible and so produce greener results.

On the other hand, families that take on an agency perspective – where the running of the business is an extension of the family’s internal dynamics, or perhaps seen as a cash cow that serves family rather than corporate goals – are less likely to take action that improves environmental performance.

If family members are more focused on their own individual needs, there can be a weaker impetus to invest in longer-term aims such as environmental transformation

If family members are more focused on their own individual needs, there can be a weaker impetus to invest in longer-term aims such as environmental transformation. Agency-driven firms may also be controlled by a diverse range of family members who have differing interests and goals, making it harder to form a consensus around topics such as sustainability.

Agency can also act as a blockage to greener practices if it opens the door to nepotism, favoritism, or family entrenchment; for example, when older generations give too much power to ill-qualified offspring.

This can create skills and experience gaps that leave firms worse off and less equipped to address critical and complex business challenges such as sustainability, as well as resulting in low motivation and productivity among non-family employees.

At the same time, if a family firm suffers from some of the agency-related problems listed above, it may struggle to attract adequate financial resources, in turn limiting the funds available for environmental activities. There can even be an additional condition – agency costs – attached to any financing arrangements, with lenders requiring the monitoring of borrowers and overseeing of collection systems.

While the picture is nuanced and complex, we see several ways in which families can implement more impactful environmental practices.

Family businesses tend to have impact investment at their core. Their owners are often ideals driven: not only do they want to run a successful business, but they wish to do so in ways that do good for all their stakeholders. Assuming their core business operates profitably, the question becomes how to organize available resources to incorporate green goals as part of their ethos.

Given the significant challenge that comes with realizing a high level of environmental performance, and the transformation necessary to do so, it makes sense to seek external, professional help. This can be a tough call for older family members who believe in their own managerial abilities, and also for younger members whose benefits might stem from their status as family insiders. However, successful sustainable transformations require competencies and perspectives that do not readily exist in most businesses.

Assuming a firm’s general willingness to improve environmental performance, its owners can then turn to using the traditional strengths of family firms to advantage.

One possible starting point is seeing whether environmental goals can be incorporated into the ideas of longevity and the legacy and traditions held dear by many family firms, perhaps through a revision or creation of the family’s values or constitution.

Firms could also encourage management and staff to think of the influence they have beyond financial performance, especially in terms of the personal emotional impact that comes with knowing the business is either damaging or protecting the environment.

Other non-financial forms of wealth that stem from doing business, such as purpose and pride, could also be emphasized to show how all stakeholders might gain from the pursuit of non-economic goals.

Many family firms also tend to foster stronger ties with their workforces and communities. Can these relationships and a sense of common purpose be harnessed to promote and improve the impact of environmental practices?

Our research showed that the way family firms communicate about their environmental performance does not often reflect reality: actual performance in terms of environmental operational practices falls short of the impression created by their communications.

Alongside putting in place plans to improve their environmental practices, firms should look at the role that communication has to play in allowing them to manage and meet the expectations of external stakeholders such as customers, suppliers, regulators, and communities, leading to an improvement in the firm’s legitimacy and reputation.

Our research challenges assumptions that give greater credit to family businesses for their environmental performance, due in part to the idea that such firms are run in a sustainable and responsible way to create value over generations.

While the picture is nuanced, some family firms clearly do better than others – especially those that do not both own and run the business, but rather have various governance or operational practices and structures in place involving non-family professionals.

At the same time, internal and external financial constraints, coupled with talent shortages and classic family business dynamics such as tensions between generations, diverse interests, non-corporate goals, and nepotism can make it harder for family firms to excel in sustainability, given the resources, decision-making agility and expertise required.

Nonetheless, family firms do tend to be long-term oriented – seeking to transfer the business or its value across generations – and this can be leveraged in different ways to boost environmental performance.

Incorporating more environmental values into a business’s culture or values and becoming the kind of actor other businesses, employees, and stakeholders want to work with should be a relatively straightforward task. Somewhat harder will be matching those aspirations with execution.

For family firms and their advisers, the priority should be to move from agency to stewardship, doubling down on their reputation for responsible longevity to put measures in place to improve their environmental performance.

Professor of Entrepreneurship and Family Business

Alfredo De Massis is ranked as the most influential and productive author in the family business research field in the last decade in a recent bibliometric study. De Massis is an IMD Professor of Entrepreneurship and Family Business at IMD where he holds the Wild Group Chair on Family Business and works with other universities worldwide.

Research Fellow and Term Research Professor at IMD Business School

Ivan Miroshnychenko is Research Fellow and Term Research Professor at IMD Business School, and Affiliate Research Fellow at Sant’Αnna School of Advanced Studies (Italy). He carries out research on economics and management of family business and sustainability that has been published in top academic journals.

17 July 2024 • by Michael R. Wade, Evangelos Syrigos in Sustainability

Companies that excel in both digital and sustainable transformation attract a stock market premium, according to research. So, how do you tap into that value? ...

11 July 2024 • by Stéphane J. G. Girod in Sustainability

A series of watershed events forced CHANEL out of its comfort zone, culminating in the launch of CHANEL Mission 1.5°. With this new strategy, the luxury fashion house embarked on a journey...

5 July 2024 • by Avni Shah in Sustainability

Creative industries have a key role to play in creating positive social change. Here are six key insights to help them achieve their goals. ...

3 July 2024 • by Richard Baldwin, Salvatore Cantale in Sustainability

The EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will impose comprehensive and standardized sustainability reporting responsibilities on firms, adding unprecedented complexity to mergers and acquisitions. ...

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience