Digital sustainability: it pays to be a leader, not a laggard

Companies that excel in both digital and sustainable transformation attract a stock market premium, according to research. So, how do you tap into that value? ...

by James E. Henderson, Ansgar Thiessen Published 27 April 2022 in Strategy • 12 min read •

What is the source of creating and delivering great business strategies? In today’s world of diversity and inclusion, the traditional strategy planning process, involving the top team working with a well-known strategy consulting firm to create thick PowerPoint decks of initiatives which are then cascaded throughout the company just doesn’t seem to cut it anymore.

Take the example of Tim Hortons, the leading quick service restaurant chain in Canada, which merged in 2014 with Burger King to form Restaurant Brands International. Armed with new leadership, Tim Hortons settled on a new strategy focused on product innovation, franchisee performance, and greater cost control. The strategy came from the top communicated mainly through PowerPoints and townhall presentations. A team of young, hardworking “analyst types” were hired to implement the new strategy. Many of the more experienced Tim Hortons employees were let go.

What happened? The franchisees were overwhelmed by new product introductions, angered by the new performance audits, and furious with the new owners’ desire to shift additional costs onto them. In the span of two years, trust in the brand across the country plummeted from its previous top spot. By late 2019 the company realized something had to be done to regain the lost trust with the franchisees and Canadian public.

Cases like Tim Hortons can be found across industries, in which well-intended strategies devised by the top team eventually fail, resulting in decreased profitability, unenamoured customers and devastated company cultures.

And yet it does not have to be this way. Many organizations including Roche Diagnostics, Swiss Re, Allianz, Barclays, ericsson, adidas, Voestalpine and Stora Enso, have approached strategy development in a very different way, by including their employees, suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders from the start. This article pulls together the lessons learned from major global companies on their more inclusive strategy journeys.

Academic research has shown that organizations whose employees, especially middle management and salaried workers, feel deeply connected to the purpose and are clear about the strategy outperform others.

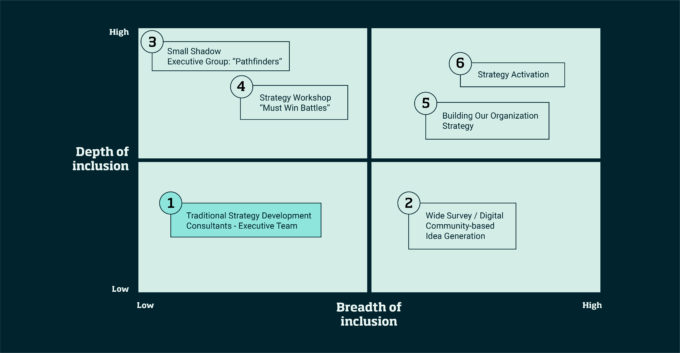

Inclusion in the strategy process is a great way to generate this connection to the purpose (or the “why” of strategy) and to create clarity on the “what” and “how” of strategy. Yet, leaders have often struggled with including more in the strategy process because of a breadth-depth trade-off.

Breadth of inclusion concerns the number of employees, and eventually external stakeholders outside of the core leadership team concerned in the strategy creation and activation process. This could range from a few, such as a task force, to the entire organization and beyond.

Depth of inclusion is seen along a commitment continuum. Participation is simply the request for information from others with the potential provision of recommendations (without the necessary request for providing recommendations). Involvement is the provision of data and enablement of discussion. Engagement includes involvement and being part of the decision making. Finally, commitment includes engagement and the emotional connection behind the decisions being made.

Traditionally, executive teams proceeded as broadly as possible through surveys, interviews and so on, but would expect little depth in commitment. Alternatively, they would call upon a coalition of leaders outside the executive team to focus on generating options or committing to a small number of initiatives which they would then cascade into the organization. The following examples show when breadth or depth of strategy inclusion can be best used.

The general manager of Roche Diagnostics Germany decided, when overhauling the drugmaker’s strategy in the country in 2015, to ask all 900 employees for their views on how it could play to win in the future. The tool used was a simple survey with a few questions which garnered a response rate of over 80%. The results were incorporated into its new strategy, leading to a significant increase in employee engagement. One year later, the general manager became the CEO of the leading division of the company.

Stora Enso’s CEO wanted to develop a new strategy for the Nordic pulp and paper company which employed around 25,000 people. Rather than rely on his top team which was made up entirely of Nordic men in their early 50s and who had spent the previous three years consolidating and re-focusing to stave off bankruptcy, he established a shadow board of 15 “pathfinders”. Their job was to report back on how other industries had completed successful transformations and provide growth options for the company going forward. A few years later, Stora Enso decided to broaden out their strategy understanding through a “Pathbuilders” leadership program. Over three years, they developed 600 leaders across the organization looking at how to accelerate Stora Enso’s strategy. It was assumed that in turn these leaders cascaded the insights to their own areas of responsibility. Employee engagement gradually improved over time.

Reeling from the impact of the financial crisis, the General Manager of NetApp Europe decided that a deeper level of inclusion was required to build out its strategy for the next few years and capitalize on the megatrend of cloud-based computing. Rather than huddle with his own team, he opened the process to a wider community of about 40 key opinion leaders in the organization who collectively decided and committed to a path forward known as their “Must-Win Battles”. They were so convinced by the process that they applied it to their strategic channel partners. The inspiration, choices and commitments were then filtered throughout the approximate 5,000-person top 10 “Great Places to Work” organization.

While the above programs all proved successful in their own ways, they still came up against a breadth-depth trade off. Based on our observations and today’s digital technologies we outline two examples below of how to incorporate both into your decision-making on strategy.

Inclusion through a BOOST journey: let us return to the newly promoted CEO of Roche Diagnostics Centralized and Point of Care Solutions. Drawing on his experience in Germany, he decided that he wasn’t going to just implement the proposed strategy handed down to him by the leadership team. Instead, he opened the process to the whole organization. Needless to say, the Head of Strategy at the time was not amused but agreed to play along. Over a six-month period, the strategy team achieved 50% engagement through voluntary means reaching 800 people. They conducted over 50 three-hour strategy workshops on where to play, how to win and the capabilities to get there. These workshops produced 11,300 ideas digitally, which were further collated, understood, synthesized and fed back to the organization.

As a result of their “Build Our Organization Strategy Together” or BOOST approach – the company decided to shutter a factory in Boston and re-prioritize some projects. Despite some difficult choices, employee engagement for the division increased sharply. One year later, the CEO was asked to take over the whole of the Roche Diagnostics division (36,000 employees). And guess what, he did it again.

Inclusion through a Strategy Activation journey: Swiss Re Corporate Solutions, the direct commercial insurance business unit of the global reinsurance company, employs 2,500 people and provides insurance cover and services to clients globally with annual premiums earned of $5.3 billion. For many years, the division had floundered under an unclear strategy, notching up large losses until 2019 when Swiss Re decided to prune unsuccessful businesses and introduce new products and services, which are close to the company’s core competences and offer future revenue streams. Yet internal surveys showed that most staff did not understand the elementary cornerstones of the new strategy and were unable to connect the dots to their personal contribution – despite communication efforts such as townhalls, newsletters, briefing calls, and articles on the intranet.

A cross-departmental group of young leaders, sponsored by the CEO, took up the challenge of activating rather than communicating the new strategy through an interactive digital platform, involving the entire company across the globe. First, the team created a comic-style Big Picture, which portrayed the business unit’s history, priorities, and initiatives as well as its future ambitions. The picture has been developed by the employees themselves and is deep in content, as it incorporates the many thought-through chapters of the wider Corporate Solutions strategy.

Employees were then asked to reflect on the “Big Picture” and explain the strategy story to fellow-employees, which resulted in the entire company telling its strategy multiple times. Corporate Solutions then run so-called “expeditions”, in which 350 employees taking the role of a moderator, run digital workshop-style sessions, in which, again, the entire workforce deepens on elements of the Big Picture in small groups of around eight. These group moderated sessions are accompanied by “single player mode” sessions, in which employees intensify their personal contributions towards the company’s strategy.

With a participation rate beyond 85% in certain expeditions with the highest category of statistical representation and an average rating of 4.5 out of 5, these sessions aim beyond rationalizing content but rather creating it. For example, co-developed business models for Digital & Data are now being implemented by the respective unit. This represents a cross-divisional and pan-global engagement never seen before in the history of the company. The Big Picture is meanwhile used for steering annual priorities for new business pitches, in client meetings, during offsites or townhalls – as a reference point to literally understand the bigger picture. Accompanied to date by two expeditions on average per year, on specific areas of the strategy and always with the entire workforce – aiming consistently at visible changes.

The evidence is clear: including more in the strategy process can result in a greater middle manager and salaried employee connection to the company’s purpose (the why of strategy) and strategy (the what and how) through higher employee engagement. And by resolving breadth-depth trade off through digital means, this connection becomes even stronger. Consequently, strategy implementation becomes much smoother.

Yet, when we polled around 200 senior executives on this topic, roughly two-thirds were reticent to address the breadth-depth trade-off wanting to stick to more traditional methods They were unwilling to engage their whole organization and cited seven main concerns:

Many executives were concerned that the strategy process would become too time-consuming if it tried to include everyone in more depth. After all, aren’t leaders paid to make decisions? Our response is that investing time upfront to ensure that staff are clear and behind the strategy will mean employees are more energized to come to work in the long run.

Others worried that once the inclusion genie was let out of the bottle, it would be hard to put back in, especially during a crisis when quick decisions often need to be made to ensure survival. We pointed to the example of Maersk Liner which was losing eight million euros ($8.8 million) a day following the 2008 financial crisis. Instead of establishing where to cut at the top they established a fully inclusive Back-In-Black program and successfully found pockets of savings.

Another concern was that asking for help from others would imply weakness and show vulnerability in the face of uncertainty. However, research has shown that leaders who show vulnerability come across as authentic and build trust among their followers.

Other leaders have told us that creating the broadest possible inclusion in strategy development is simply “pretend commitment”. People generally agree to everything that is stated but then when it comes to the real work, nothing changes. Cynics among the employees would argue that full inclusion is often a smokescreen of pretend listening, pandering to the masses, without any change based on the feedback provided. To make inclusive strategy work, the time between listening, incorporating, and synthesizing ideas, revising the strategic choices and feeding it back to the organization should be short. Otherwise, full commitment, full engagement of “my job has meaning” and “management’s expectations are clear” can turn into “we have been through this too many times”.

Many executives argue that inclusive strategy will create empowerment. No doubt about it. But with empowerment comes accountability and extra pressures for delivering. The more cynical executives would argue that most employees do not want the extra pressures. They want to be heard but they do not want necessarily the extra accountability. There may be some truth to this statement. But consider the opposite approach: no empowerment, no accountability versus lots of empowerment, concerns about the extra pressure. Enough said.

Others worry about creating the false expectation that all employee views are taken into consideration. And when they are not (due to choices having to be made), this may result in reduced engagement. Yet, research has shown that as long as the process is deemed fair and employees believe their interests and perspectives were taken into account, they will commit to the outcomes.

Another argument we hear is that full disclosure could jeopardize any competitive advantage and risk sensitive information on potential acquisition targets or trade secrets spilling into the public domain. One way to handle this is to acknowledge upfront that there are certain issues that simple cannot be discussed or disclosed. In addition, it is important to recognize that competitive advantage today is fleeting and can be rapidly copied. Improving your organization’s execution capability, for example through a more inclusive strategy, may be the real source of competitive advantage. Thus, even full disclosure may not be as detrimental as perceived.

These seven concerns against inclusive strategy: Process, Retreat, Openness, Commitment, Empowerment, Expectations and Disclosure also paint another picture for leaders. Take the first letter of each and spell the new word. What is our advice to those who are still sitting on the fence? PROCEED, just proceed. What is there to lose?

Rather than start small and testing it out, try going as broad and deep as possible, despite the uncertainties about what will be said or what the reactions will be. As the CEO of Roche Diagnostics stated after taking over the division and applying the same approach: “When you are in this position leading 36,000 employees, you may have 20% of the answers. The rest you must rely on from the whole organization. Indeed, I am not coaching others, I am being coached by them.”

Professor of Strategic Management at IMD

James E. Henderson is Professor of Strategic Management at IMD, Program Co-Director of the Leading Sustainable Business Transformation program, and Program Director of the Strategic Partnership course. He helps companies achieve and sustain their competitive advantage either at a business unit, corporate, or global level through directing custom specific executive programs, facilitating strategy workshops, or teaching MBAs and executives.

Member of the Operations Management Committee at Swiss Re Corporate Solutions

Dr. Ansgar Thiessen (Head COO Office), is member of the Operations Management Committee at Swiss Re Corporate Solutions. Before joining Swiss Re, he held leadership roles in Management Consulting. For over a decade he has been a thought leader on the question of how organizations foster acceptance and assertiveness towards strategies or during large-scale transformations. Thiessen is also the author of the book Playbook Strategy Activation and lecturer at Copenhagen Business School on the topic.

17 July 2024 • by Michael R. Wade, Evangelos Syrigos in Competitiveness

Companies that excel in both digital and sustainable transformation attract a stock market premium, according to research. So, how do you tap into that value? ...

8 July 2024 • by Richard Baldwin in Competitiveness

As the world’s largest democracy prepares to overtake China in terms of economic growth, it offers a huge investment opportunity, explains IMD’s Richard Baldwin....

26 June 2024 • by Arturo Bris in Competitiveness

Don’t be deterred by doom-laden narratives. To create societies that are prosperous and inclusive, it’s time for leaders to focus on facts and future readiness, says Arturo Bris...

14 June 2024 • by Howard H. Yu in Competitiveness

This weekend’s G7 summit will see renewed calls for protectionist measures against Chinese EV manufacturers. But tariffs would be misguided and universally damaging, warns IMD’s Howard Yu ...

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience