Digital sustainability: it pays to be a leader, not a laggard

Companies that excel in both digital and sustainable transformation attract a stock market premium, according to research. So, how do you tap into that value? ...

by Boris Thurm, Sophie Bürgin, Jordane Widmer Published 21 September 2022 in Sustainability • 9 min read

In 1921, American chemist Thomas Midgley discovered that a fuel additive, tetraethyl lead, made cars run better and more efficiently. Shortly after, leaded gasoline was commercialized by the Ethyl Corporation and widely adopted, contributing to economic growth and creating jobs. But the fuel had a major, and tragic, downside: widespread lead pollution, millions of deaths, and lower IQ levels.

While lead was already known to be toxic in the 1920s, it was only a century later, in 2021, that all countries finally banned leaded gasoline. This story illustrates how failing to consider the environmental and social impact of our economic activities can have severe, often unintended, consequences. Since what we measure affects government policy, investment decisions, and business strategies, flawed and incomplete measurements can only lead to distorted or bad decision making.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which measures the monetary value of all goods and services produced in a country within a given time period, was widely adopted as the global standard for measuring a country’s economy following the Bretton Woods conference in 1944. Since then, many economists and scientists have acknowledged its shortcomings, in particular its failure to account for the indirect costs and benefits that arise due to our economic activities – known as externalities. Still, it persists as the main way that governments worldwide gauge their economic output.

To remedy some of GDP’s shortcomings, and to contribute to better-informed policy and decision making globally, we propose a new indicator: Green Domestic Product (GrDP), which extends the scope of GDP to factor in the depletion of natural, social, and human capital. Simply put, this new measure is calculated by subtracting the external costs associated with producing goods and services from the standard measurement of GDP.

In its current form, our model for GrDP is only capable of measuring the environmental and social degradation caused by three groups of pollutants: greenhouse gases (GHGs), air pollutants, and heavy metals. These are currently the easiest to track on an international level and have the greatest influence on the urgent challenges facing governments and industry today.

Most economic activities, ranging from fossil fuel combustion to industrial and agricultural processes, produce GHGs. As we know, these are responsible for climate change, which negatively impacts society and ecosystems by warming the planet, altering precipitation patterns, and causing biodiversity loss.

Industrial and agricultural processes also emit various air and other pollutants that can be harmful to human health when directly inhaled and can contaminate water and soil, reducing the yield of crops and biomass production in forests.

The Impact Pathway Approach framework allows us to quantify and value externalities in five steps.

There are several methods to convert externalities into monetary terms:

Avoidance costs: The costs of preventing pollution by avoiding the release of an additional unit of pollutant.

Damage costs: The costs incurred by the pollution – for example, agricultural production loss due to a decrease in crop yields.

Abatement costs: The costs of reversing the damage caused by the pollution, such as healthcare spending to treat disease.

For our purposes, we value the externalities caused by air pollutants and heavy metals using the damage cost approach, while we use avoidance costs for GHGs. Quantifying the impact of climate change is prone to significant uncertainty and depends on future scenarios. As such, the calculated values for the social cost of carbon varies from a few euros – or could even be negative – to several thousand euros per ton of CO2e.

Valuing externalities sometimes requires pricing the priceless, e.g., excess mortality. Although this might raise ethical questions, the alternative – that is, not accounting for this impact – is arguably worse. One way to value mortality is the value of statistical life, which measures how much people are willing to pay for a reduction in their risk of dying from adverse health conditions.

Let’s illustrate the difference between GDP and GrDP by taking the example of a pharma company. The production of drugs has clear benefits to society and contributes positively to GDP and GrDP. However, chemical synthesis relies on energy-intensive processes, and the associated combustion of fossil fuels leads to the emission of GHGs and air pollutants. In some cases, we can compensate for some of the negative externalities – for example, by treating people for health problems, potentially using drugs whose production partly contributed to the issue – or repairing buildings where the stonework has been degraded by air pollutants. In this case, overall welfare hasn’t increased; at best it has stayed the same.

Nonetheless, the healthcare expenditure and other investment involved would translate into an increase in GDP or value added to the economy. By contrast, by using GrDP, these expenditures would, in theory, equalize the external costs, meaning GrDP would stay constant. Similarly, if no measures were taken to compensate for the negative impacts, GDP would stay the same but GrDP would decrease.

As well as offering vital context and data for industry, businesses, and investors, our GrDP framework provides potentially game-changing information for national policymakers as countries manage the transition towards greener economies in the fight against climate change. To illustrate this, let’s take a look at the GrDP per capita of European countries in 2019 and the share of external costs with respect to GDP.

As illustrated in our interactive GrDP tool below, Luxembourg, Switzerland, and Ireland have the highest GrDP per capita, while Bulgaria, Romania, and Croatia have the highest external costs per economic output. Overall, our analysis shows that countries with the highest GDP tend to have the lowest external costs, and thus the highest GrDP.

Why is this? It is because countries with high GrDP typically have an economy that relies on services – the economic sector that emits the least pollutants per unit of value added – and a higher share of renewables in their energy mix, in particular fewer coal power plants.

While external costs remain significant – accounting for more than 10% of GDP in 16 of the 31 countries studied – they have fallen since 1995 when all countries except Sweden had external costs above 10% of GDP.

Back then, Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, and Slovakia even had negative GrDP with the depletion of environmental, human, and social capital exceeding the economic production of the country. The situation was the same in the United Kingdom before 1992.

Since 2000, GDP in European countries has grown by about 74% while external costs have decreased by about 44%, raising the idea of a decoupling between economic growth and air pollution. Results for Switzerland indicate that this decoupling persists, especially when we consider imported GHG emissions and not only domestic emissions.

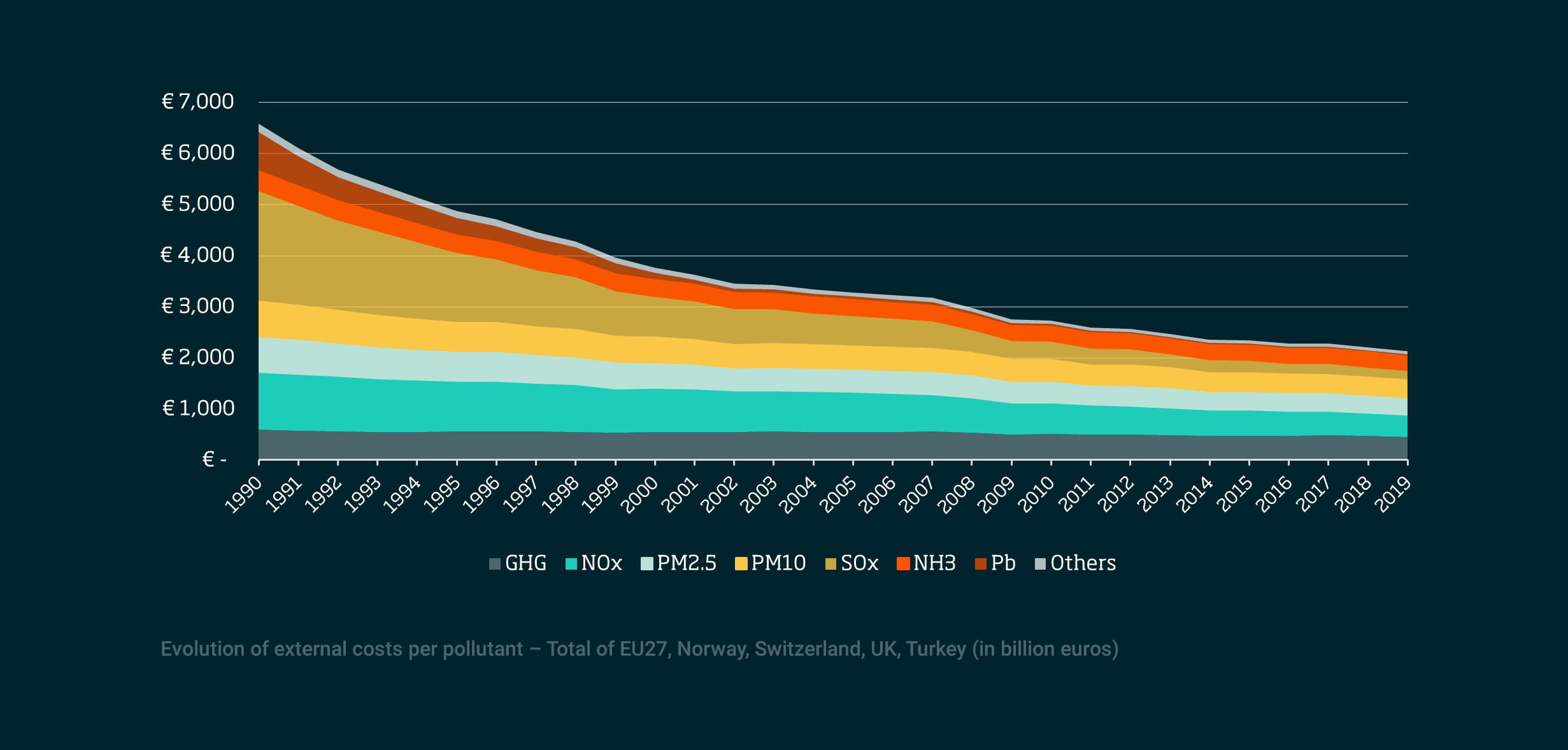

Nonetheless, both GHG and air pollutants remain critical issues, as illustrated in the figure below.

On the positive side, externalities due to heavy metal emissions have reduced to levels close to zero, thanks to the implementation of regulation in 2003 which targeted the reduction of emissions stemming mainly from waste incineration and industrial processes. The spread of unleaded gasoline during the 1990s also helped reduce these emissions.

However, air pollutants such as NOx and SOx are still responsible for large external costs – more than €1.5 thousand billion in 2019 – primarily due to their negative impact on health. As for GHGs, the externalities due to their emissions account for about €450 billion in 2019 – and this might even be an underestimation. More troublesome, GHG emissions are not decreasing as rapidly as air pollutants.

Adopting GrDP would enable policymakers to consider the impact of all pollutants when designing policies and give business decision makers and stakeholders a clearer way to understand the true cost of industrial activity. For example, electrifying transport systems by substituting fossil fuels for renewables would contribute to reducing both GHGs and air pollutants. However, adopting synthetic fuels manufactured using captured CO2 and hydrogen could play a crucial role in reaching net zero by closing the carbon loop, but would have little impact on air pollutants which are still generated in the combustion of synthetic fuels. Decarbonization, when properly designed, could lead to significant co-benefits, and enhanced GrDP growth.

GrDP can be downscaled to provide a more detailed picture of the value added of each industry, as illustrated in the forthcoming E4S white paper Going Beyond GDP: the Swiss Green Domestic Product (2022), where we assess the decoupling between growth and pollution at the sectoral level. This increased granularity can help investors and innovators to identify industries experiencing rapid (net) growth, and, on the contrary, slow-decarbonizing industries that will require heavy investment and innovative solutions to meet the net zero target.

For business leaders, faced with growing demand from stakeholders for clear information on ESG footprint, GrDP provides additional data and a powerful contextual tool to frame their approach to impact measurement and, by extension, decision making. GrDP is only a first step towards the adoption of environmental accounting – e.g., corporate earnings before interest and taxes could be adjusted following a similar methodology to account for environmental profit and loss. Measuring and valuing external costs would enhance awareness of the true cost of activities and increase the transparency of supply chains, facilitating the choice of suppliers and potentially leading to greater pressure for industry to adopt greener practices.

Nonetheless, a systemic view is crucial when dealing with global pollution such as GHGs. For instance, electrifying the vehicle park of a company would decrease the GHG emissions (scope 1) but would do little for overall emissions (scope 2 and 3) if the electricity is produced by fossil-fuels power plants. A coordinated transition between policymakers and businesses is thus necessary.

Although replacing GDP with GrDP would be a step in the right direction, pursuing GrDP growth alone will not be enough to achieve sustainable growth.

First, by aggregating all the economic activities and externalities in one indicator, GrDP hides the differences within countries and fails to reflect social inequalities. Second, since the scope of the externalities considered is limited in our current version of GrDP, the indicator does not fully factor in the evolution of environmental, social, and human capital. For example, it does not measure plastic pollution and tells us nothing about the exhaustion of materials and minerals. It would therefore be possible to pursue GrDP growth without respecting our planet’s limits, at least in the short term.

Understanding the shortcomings of economic indicators is a crucial step in using them properly in policy and other decision making.

If adopted, GrDP, although incomplete in its mission to capture and cost all externalities, represents a valuable and vital tool for policymakers, industry leaders, and other stakeholders as the world grapples with the threat of climate change and environmental degradation. By taking the negative effects of emissions of a wide variety of pollutants into account head-on, GrDP is a more appropriate measure for the time we live in than the outdated concept of GDP. At the very least, it will support better-informed decision making, helping to shape a more sustainable future for people and the planet.

If you are interested in finding out more about the GrDp indicator and methodology, E4S researchers have published a white paper on GrDP in Switzerland, which can be accessed here.

Scientific Collaborator at Enterprise for Society (E4S)

Boris Thurm is a Scientific Collaborator at Enterprise for Society (E4S), a joint venture of UNIL-IMD-EPFL. His research focuses on the impacts of human activities on environmental resources and on the drivers behind individuals’ decision-making. During his spare time, he enjoys mountain activities such as hiking and ski-touring.

Scientific Collaborator at Enterprise for Society (E4S)

Sophie Bürgin is a Scientific Collaborator at Enterprise for Society (E4S) a joint venture of UNIL-IMD-EPFL. Her research includes topics in macroeconomics, finance and sustainability. She also is an active member of Rare Voices in Economics, and enjoys cooking and the outdoors.

Scientific Collaborator at Enterprise for Society

Jordane Widmer is a Scientific Collaborator at Enterprise for Society (E4S), a joint venture of UNIL-IMD-EPFL. His research interests include political economy, public policies and the mechanism of corruption in our economic system. As a passionate reader of literature from an early age, he no longer counts the hours spent in the company of Stefan Zweig or Alexandre Dumas.

17 July 2024 • by Michael R. Wade, Evangelos Syrigos in Sustainability

Companies that excel in both digital and sustainable transformation attract a stock market premium, according to research. So, how do you tap into that value? ...

11 July 2024 • by Stéphane J. G. Girod in Sustainability

A series of watershed events forced CHANEL out of its comfort zone, culminating in the launch of CHANEL Mission 1.5°. With this new strategy, the luxury fashion house embarked on a journey...

5 July 2024 • by Avni Shah in Sustainability

Creative industries have a key role to play in creating positive social change. Here are six key insights to help them achieve their goals. ...

3 July 2024 • by Richard Baldwin, Salvatore Cantale in Sustainability

The EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will impose comprehensive and standardized sustainability reporting responsibilities on firms, adding unprecedented complexity to mergers and acquisitions. ...

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience