Swiss banking: In search of a secure future

In light of the Swiss Federal government’s report following the Credit Suisse debacle, how can the Swiss banking sector regain its reputation for stability and resilience? ...

by Patrick Reichert Published 18 October 2021 in Sustainability • 6 min read

In 2007 came one of the most significant events for microfinance: one of Latin America’s largest microfinance organizations, Banco Compartamos, listed on the Mexican stock exchange. Microfinance is a type of banking that provides financial services to poor individuals and the ‘unbanked’.

Like other social enterprises seeking to solve social and environmental challenges alongside generating financial returns, microfinance firms face headwinds to becoming financially sustainable and independent from donors. Banco Compartamos proved it was possible.

The company has gone through the full social enterprise lifecycle: from experimental non-profit to publicly listed company, and it used subsidies from donors to do it. These financial instruments helped the company attract private capital, and shift from an early emphasis on grants to debt and equity later on, and eventually an initial public offering.

The case illustrates how subsidies, which are ubiquitous in developed economies but are often seen negatively as market distorting devices, can scale the impact of social enterprises. Indeed, the type of microfinance provided by Banco Compartamos has emerged as a key tool in the fight against global poverty in recent decades. The company helps to alleviate household financial constraints and provides the capital for borrowers to generate income.

There remains a historical and implicit bias that social enterprise is more of a charitable cause than a business activity — one major barrier is overcoming these misguided stereotypes. And although there has been an explosion of interest in environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing, large institutional investors such as pension funds typically eschew allocations to funds that invest in social enterprises until they reach a sufficient scale to justify the high transaction costs from due diligence that ultimately eat into investor returns.

Social enterprises often struggle to reach sufficient scale to cover their fixed costs in part because they lack experience and proven competencies just like all startups, while the ‘triple bottom line’ of people, planet and profit makes them appear more opaque and risky to investors. The measurement of non-financial impact is, indeed, notoriously challenging.

Philanthropists searching for social value creation alongside financial returns have stepped in to fill this gap in funding between the seed and growth stage of social entrepreneurship, through a range of subsidies such as grants, debt and equity instruments.

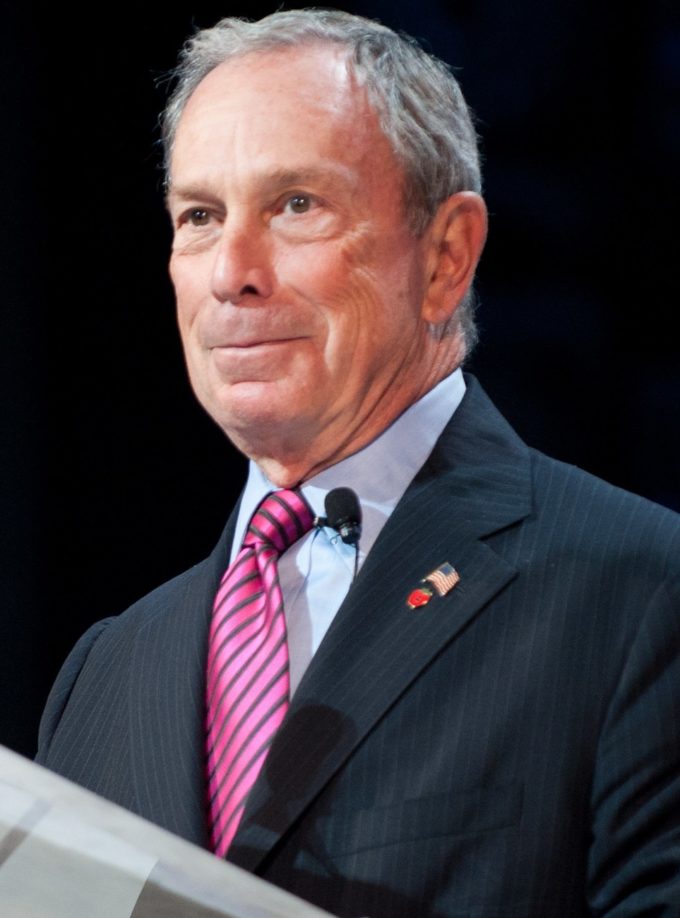

These wealthy individuals have shown an increased willingness to write large cheques in the hope of contributing to society, with the most famous examples being Microsoft founder Bill Gates, investment legend Warren Buffet, and media mogul Michael Bloomberg.

My research, co-authored with Ariane Szafarz, Marek Hudon and Rob Christensen, indicates that subsidies can help social enterprises scale up and attract commercial backers with pockets deep enough to maximize social impact. But while some subsidies open access to mainstream investors, others close the doors to Wall Street.

Some social entrepreneurs are uneasy with the idea of commercialization, fearing that it detracts from their social mission. The Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus views microfinance IPOs as a threat to the sector’s moral integrity. While there are tensions and trade-offs in balancing financial and social goals, commercialization is necessary to achieve financial sustainability and independence. Without that, altruism is merely an ideal.

To make the connection between subsidy funding and financial stability, we applied the economic concept of ‘signaling theory’ to social enterprises. It works by donors sending ‘signals’ to commercial investors through the types of subsidies they issue to social enterprises, which can both attract and deter other investors.

A crowding-in effect, when donations lead to greater private sector investment, can be achieved through subsidies that are rule bound, time limited and transparent. In contrast, crowding-out occurs when subsidies are untargeted, sticky and opaque.

In the early stages of the social enterprise life cycle, grants can be effective at attracting further financial backers because they help the beneficiaries to experiment, build prototypes and find a business model that works. In 1990, Banco Compartamos obtained a $50,000 grant from USAID, the international development agency, and from this humble origin the company began its 17-year journey to becoming a microfinance behemoth.

But once any social enterprise reaches the break-even point, relying on unconditional grants to cover all operating expenses is likely to deter investors, because it suggests the venture cannot generate enough revenue to demonstrate credit-worthiness. After all, grants imply a negative 100% rate of return for donors.

Unconditional grants, those that come with no strings attached, carry the greatest stigma. In contrast, conditional cash grants, which come with restrictions to their disbursement (such as hitting financial milestones), or limit expenditure to particular activities, send stronger positive signals to commercial funders. This is because they demonstrate a greater expectation of recoverability of credit.

The early grants obtained by Banco Compartamos came with strict reporting requirements and specific instructions on disbursement. By 1995, the company achieved operational self-sufficiency and, at this stage, its donors shifted from grants to the use of preferential debt, which refers to concessions on interest rate or grace period.

Preferential debt supports the transition from a loss-making organization to a profitable enterprise, which can attract big-ticket investors because it demonstrates commercial viability. Indeed, taking on debt means that the company has to generate revenue to strengthen its balance sheet.

In 1996, Banco Compartamos received a $2 million conditional grant in tranches dependent on performance benchmarks including a low arrears rate and high annual client growth. These conditions imposed budget constraints on the company, which sent positive signals to private investors.

However, this is not always the case. In particular, the use of grace periods, or a temporary delay in debt repayment, can deter commercial investors because it allows social enterprises to forgo their financial discipline.

On the other hand, subsidized interest rates and loan guarantees send stronger signals to funders. Credit guarantees are particularly attractive for governments wanting to support social enterprises without taking full equity stakes in companies, which is a politically sensitive subject because the taxpayer is on the hook for losses.

With that said, preferential debt, much like grants, is a time-sensitive instrument because its continued use suggests poor efficiency or the inability to scale on the part of the social enterprise, which are both likely to crowd-out financial backers.

Another option is preferential equity, or equity that comes with helpful concessions such as a dividend cap or restrictive voting rights for investors, so the social enterprise does not have to constrain its cash flow, or give away control of ownership, respectively.

Non-profits often restructure to gain access to equity funding, for example by using legal structures such as common interest companies (CICs) in the UK and low-profit limited liability companies (L3Cs) in the US. This opens up access to a bigger investment universe.

Typically, concessional investors will play an active role in the development of the social enterprise, often taking a seat on the board. This oversight and non-financial support sends strong signals to other commercial investors seeking outsized returns.

It certainly helped Banco Compartamos tremendously. Its backers brought considerable banking expertise, advising it to strengthen its loan supervision procedures and raise its monthly interest rate to boost growth from retained earnings. This signaled to investors that the company was becoming more professionalized and disciplined — both factors that strengthened its credibility.

But, dividend caps or restricted voting rights are less attractive to investors, so they send out weaker signals. Preferential equity must be designed in a way that does not limit the upside potential of commercial investors, or exit opportunities.

By 2006, Banco Compartamos obtained its full banking license and began to accept customer deposits. The final step for donors was to wind down their equity positions.

The IPO was thirteen times oversubscribed, a massive success by financial market standards, essentially translating into a return of 100 percent per year for early backers. New investors were primarily mainstream fund managers, underscoring the power for signaling to alleviate information and funding gaps while advancing social progress. Armed with an expansive toolbox of financial instruments, these findings can help public and private sector donors to optimize subsidy design.

Research Fellow at the elea Chair for Social Innovation

Patrick conducts research at the intersection of entrepreneurship, finance, and social impact, with a particular focus on the mechanisms and logics that investors use to seed investment in social organizations. He is a research fellow at the elea Chair for Social Innovation.

19 July 2024 • by Peter Nathanial, Ludo Van der Heyden, Salvatore Cantale in Finance

In light of the Swiss Federal government’s report following the Credit Suisse debacle, how can the Swiss banking sector regain its reputation for stability and resilience? ...

17 July 2024 • by Michael R. Wade, Evangelos Syrigos in Finance

Companies that excel in both digital and sustainable transformation attract a stock market premium, according to research. So, how do you tap into that value? ...

10 July 2024 • by Michael Skapinker in Finance

A rise in climate change protests against leading arts institutions spells trouble for the future of corporate sponsorship. Companies and cultural organizations must learn to manage the risks....

8 July 2024 • by Richard Baldwin in Finance

As the world’s largest democracy prepares to overtake China in terms of economic growth, it offers a huge investment opportunity, explains IMD’s Richard Baldwin....

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience