The two things that everyone values

If you look at all that has been written and studied about human motivation and human nature, you find oceans of great thinking and research, from philosophers to neuroscientists, from biologists to psychologists and sociologists. Building on this rich body of knowledge, we have distilled some of the commonalities we observe.

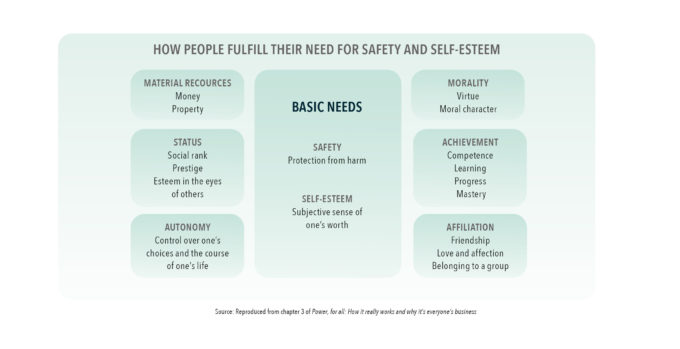

Our analysis reveals that there are two basic needs that animate every one of us. One is intuitive, the need for safety. We all need to feel protected from harm. The other is self-esteem. We want to feel we are worth something, and that we’re not just one of billions of humans roaming the earth; that our existence means something, matters to someone, that it has value.

These two drivers of human behavior, the need for safety and the need for self-esteem, are always at play when you lead. They are your anchors. The people you lead will certainly be animated by those two needs. The complication is that how people satisfy those needs changes depending on the situation, and people won’t necessarily reveal how they wish to fulfill these needs—and sometimes they might not know themselves.

But there are regularities in what people respond to in pursuing safety and self-esteem.

The six resources people seek to feel safe and worthy

People certainly value material resources — money and property — because those can buy you safety. Money can also make you feel deserving of esteem because it signals that you’ve done well for yourself. It can make you feel superior to those with less, giving you social status, another resource people value deeply. The appeal of material resources and status is universal. That’s why job security and compensation are important motivators. And that’s why fancy job titles, corner offices, and even purely symbolic recognition, like a “mentor of the year” designation, matter to people: they make them feel special, and therefore worthy.

But people value more than just money and prestige. Other, more psychological resources also allow people to fulfill two basic needs for safety and self-esteem.

One of them is a sense of competence and achievement, a feeling that you are doing something well, that you are succeeding, that you’re improving and learning. When you give the people you lead a sense that they’re becoming better at something and that they’re growing in their professional prowess, then you will have influence over them. You will control a resource they value: a feeling of increased mastery, the sense that they’re are accomplishing something. Research shows that this feeling of progress is an important source of motivation for people at work. The manager who can create an environment in which people experience progress will have influence on their behavior.

Audio available

Audio available