Bridging the Capability Gap to Go Global

Participants from around the world gathered at an IMD Discovery Event in September 2016 to learn how companies can bridge the capability gaps that prevent them from benefitting fully from an increasingly globalized world. They explored why these gaps occur and shared their experiences in overcoming them. They also learned why balancing exploitation and exploration matters for organizations and about the importance of using a flexible international operating model to optimize the local–global trade-off.

People act as if globalization were a new phenomenon. In fact, it started around five centuries ago when the first navigator to sail around the globe returned laden with valuable exotic spices but with a drastically diminished fleet and crew. The huge losses, which in this case were borne by just one investor, highlighted the risks associated with such journeys and led to an innovation in the ocean exploration business model: the use of a joint stock company to spread both the risks and the rewards across a pool of investors.

Organizations can and must globalize

Organizations create shareholder value by innovating, developing and selling goods and services. Increasingly, international and global companies must also globalize by seeking out new markets and developing products outside their local markets. Evidence suggests that globalization is continuing to increase. Foreign direct investment has gone up 9% since 1996, and more global companies are now originating in emerging markets. Fortune’s Global 500 companies list highlights important changes. In 2005, 7% of the companies were based in China but by 2014 that number had more than tripled to 26%. During the same period, the number of North American companies on the list had fallen from 38% to 28%.

Aspirations outweigh ability to execute

The road to globalization can be bumpy for any company. One of the main hurdles is bridging the capability gap. IMD and the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) surveyed more than 350 executives from 55 countries about their organization’s aspiration to globalize and their capability to do so. The results revealed that across all regions and industries 72% of the organizations aspired to globalize but only 49% evaluated themselves as strong in execution. The capability gaps identified can be clustered as follows:

- Learning & agility: Willingness to understand/adapt to local markets via new products and business model changes.

- Leadership & governance: Strong commitment from the top to push a global agenda, establish global priorities and align incentives.

- Business capabilities: Core business skills needed to compete in complex markets, such as global supply chain and local go-to-market capabilities.

- Organizational & executional alignment: Ability to design and adapt processes and systems and manage the HQ–Region relationship.

The world has come a long way from the traditional model whereby MNCs based in the US and Europe knew who their competitors were and fully understood industry dynamics. Today, global organizations are more likely to compete against local players in regional markets. All global firms – in both established and emerging markets – must navigate these new realities by building up their organizations’ capabilities and bridging the gaps.

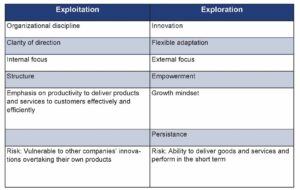

Ambidexterity: Balancing exploitation and exploration

Today’s global companies need to balance the exploitation of their existing knowledge base in the short term against the need for longer-term exploration, or innovation, of new products, services or business models. Both capabilities are needed to ensure durable survival. This calls for ambidexterity! Yet, only 2%-4% of companies successfully achieve the optimal balance. Those that do, such as Lego, outperform others in terms of sales growth and total shareholder returns.

However, ambidexterity requires two opposing mindsets as shown in Table 1, yet companies must excel at both. If they neglect exploitation, they risk bad performance and eventual decline. If they fail to innovate, they risk exploiting themselves straight to the graveyard. The technology industry is rife with examples of companies that failed to get this balance right: Nokia, Blackberry, Kodak are just a few.

Alphabet, the holding company that owns Google, has so far achieved that balance. Its structure allows Google’s exploitation expertise in selling targeted advertisements to thrive while also allowing space for the exploration of new products, services and business models. If, or rather when, Google’s exploitation advantage erodes, one of its other entities can hopefully provide the next revenue stream to exploit.

Successful, organizationally ambidextrous organizations “think differently:”

- They focus more on transformation, innovation, experimentation, agility, collaboration and platforms versus exploiters

- They project a more positive outlook and focus on long-term metrics

- Their top management teams demonstrate strong commitment to their strategies, including accelerating change and trying new things; scanning early adopters and competition for new opportunities; and driving collaboration within their industry to build an ecosystem that supports innovation.

The pharmaceutical industry built such an ecosystem to foster collaboration across companies and academia. It is an essential aspect of the industry’s new medication pipeline.

Optimizing the local– global trade-off

The more companies internationalize and add diversity to their geographic footprint, the more they create a globalization aspiration–readiness gap. One of the key ways to close this gap is to learn how to get the local–global trade-off right. Too much focus on global execution can lead to bureaucracy and slow decision making, resulting in lost opportunities and alienated managers when those managers could in fact contribute valuable local knowledge. Conversely, using a largely local model can prevent organizations from exploiting their scale and reaping the rewards of learning from and spreading best practices.

As a first guideline, companies need to carefully craft the optimal local–global balance based on their overall strategy. Which markets require local know-how? In which industries and geographic markets should companies leverage their global scale? Valuable new opportunities increasingly originate in diverse, non- Western local markets where customers face very different day-to-day realities and expectations. Organizations that simply duplicate their home-market model risk missing out on potential innovations originating in those markets and/or misunderstanding customers’ needs. For example, US-based electronics store Best Buy imported its model into China, organizing its electronic goods by families of products (washing machines, telephones, etc.), for which it negotiated low common price-points. However, Chinese customers expected stores to be organized by brand with dedicated sales representatives with whom customers could negotiate prices directly. After five years it gave up.

However, an “all-in” local model is equally risky. In Germany, Walmart tried to compete with local discounters Aldi and Lidl but it never succeeded in beating them; it lacked the local contacts needed to negotiate the lowest prices in Germany. In new markets, companies must exploit their global scale to gain a competitive advantage against local incumbents. Although Walmart failed to do this in Germany, it did so when it entered other European countries, China and South America. Now it has the second-largest cross-border retail presence.

The need for organizations to more seriously consider a local–global framework has stemmed from the rise of emerging-market firms that use different models. Just 15 years ago the oil & gas industry was dominated by International Oil Companies (IOCs), which simply

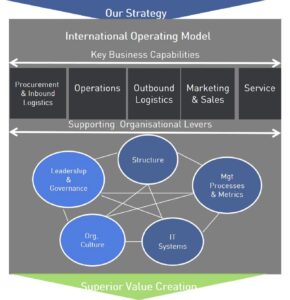

replicated their business model into each new market they entered. That ended when National Oil Companies (NOCs) from emerging markets, especially China, used their vast reserves to offer other emerging markets local development opportunities such as building infrastructure. Their model was much more responsive to local markets than that of the IOCs, which have since been forced to adopt a more local– global model. The second guideline is to design the company’s international operating model (IOM) to achieve the right local–global balance (see Figure 1). The IOM is a tool that helps companies make choices related to coordinating cross-border activities by allowing them to articulate how they will operate and get things done in each country and, in particular, how they will coordinate the relationship between HQ and local operating units. Every company defines its unique IOM taking into account the different external contexts in which it operates, its industries and its specific capabilities. Research shows that those with a flexible IOM perform better than others. When implementing its IOM, a company must:

- Design an IOM that is aligned with and that supports its strategic objective

- Decide which core activities are needed to deliver its value proposition to customers

- Optimize and align the levers – organizational structure, management processes and metrics, IT systems, structure, leadership and governance, and organizational culture – to support its strategy.

Furthermore, the IOM and the levers must all work together systemically. If the organizational structure requires employees to communicate with each other and share information and knowledge, it should promote this behavior through structures such as performance assessments that reward cooperation. Companies also have to identify which elements block the successful implementation of the strategy and find solutions to those bottlenecks. In other words, companies have to deliberately think about the local–global trade-off for each business activity and lever.

Practically speaking, that involves adapting and addressing the four types of capability gaps identified above. Consider what that means for business capabilities (core business skills needed to compete in complex markets) such as procurement and inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and services. When French aerospace company Safran changed its business model from selling aircraft engines to selling aircraft engine hours its capability requirements also changed because the skills needed to manage and maintain engines that remained on its own balance sheet were totally different to those needed to simply sell engines.

Because global companies all have their own complex mix of strategies, capabilities and levers, each organization must identify its own unique, optimal combination depending on the context in which it operates. Those that get it right – i.e. aligning their key capabilities with strategic objectives, deciding on the local–global trade-offs and ensuring the hardware and software supports them – deliver superior value, customer experience and profits.

Conclusion

The adage “think global, act local” is outdated. The rise of emerging markets challenges the “think global” mindset, which suggests an overly limiting home- centric perspective. Rather, organizations must adopt a multi-focal and inclusive mindset.

Globalization is constantly changing, which means organizations will need to regularly revisit the way they address the exploitation-exploration and the local- global trade offs.

Discovery Events are exclusively available to members of IMD’s Corporate Learning Network. To find out more, go to www.imd.org/cln

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

In that article I explained that modern safety leaders need more than just technical skills to survive in a VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex & Am...

The case study delves into strategic transformation and leadership transitions at Unilever since 2009. Unilever has been an industry leader of busi...

The parenthood wage gap – different wage levels for employees with versus without children – is one of the key factors contributing to gender wage ...

The case study examines recent aviation safety concerns at Boeing, focusing on manufacturing issues, leadership decisions and regulatory oversight....

The case is seen through the eyes of the newly appointed supply chain director at a cosmetics company based in Berlin. The general manager has task...

Few Business to Business (B2B) marketplaces have succeeded. Metalshub has successfully combined a software platform as a service, with a marketplac...

The case focuses on Contabilizei, a Brazilian startup providing online accounting services for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The case ...

in Safety and Health Practitioner 29 January 2019

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

in I by IMD 24 June 2024

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Case reference: IMD-7-2457 ©2024

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Case reference: IMD-7-2546 ©2024

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications