A decade after the Paris Agreement, the consensus on climate action is showing signs of strain. The energy transition is underway – investments in renewables are rising, net-zero pledges abound, and sustainability is on the agenda in boardrooms – but the context has changed dramatically. A sharp rise in energy prices due to COVID-19 and war in Ukraine has jolted markets. For many governments, climate ambitions have been tempered by the need for energy security and energy affordability. Corporate leaders need to understand how energy impacts their businesses at the macro (energy markets) and micro levels (energy consumption and usage).

Energy security in Europe was taken for granted for years. Underinvestment in domestic capacity and overreliance on imported fossil fuels, particularly Russian gas, left the region vulnerable. Soaring energy bills made headlines, fueling populist narratives and prompting costly government interventions.

The energy trilemma, an old but powerful concept, encompasses the interlocking goals that must be balanced: environmental sustainability, energy security, and energy affordability. In recent years, the emphasis has tilted toward sustainability, but the center of gravity is shifting. It’s a strategic challenge for business leaders with direct implications for competitiveness, supply chain resilience, and long-term value creation. Navigating the energy trilemma is becoming basic strategic foresight.

More than just an academic framework, the energy trilemma is a reality for governments, industries, and citizens. It describes the competing and often conflicting demands placed on energy systems: achieving environmental goals (sustainability), ensuring uninterrupted access to energy (security), and keeping energy costs manageable (affordability). While aligned in principle, these goals frequently pull in different directions during crises or when technologies underperform. Ideally, all three dimensions should balance, but progress on one front often comes at the expense of another: a rapid decarbonization drive may create volatility or raise prices; efforts to subsidize fossil fuel consumption may keep prices low but delay clean energy investment; overreliance on a single energy source, even a clean one, can make countries dependent on external suppliers.

Tackling one dimension on its own is impossible. Political cycles, technological breakthroughs, climate disasters, and market disruptions can all shift the balance. Companies that commit to sustainability goals, electrify operations, and invest in clean energy are becoming active participants in the trilemma. Their choices can tilt the balance, and their success depends on recognizing the trade-offs.

From global consensus to strategic fragmentation

The 2015 Paris Agreement marked a rare moment of global alignment. Nearly all nations pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and transition toward a more sustainable energy future. Business responded enthusiastically: ESG investing surged, climate risk disclosures became mainstream, and “Net zero by 2050” entered the corporate lexicon.

That momentum has now faltered. In the US, a political backlash against ESG and climate regulation has gained traction. In Europe, the war in Ukraine forced a temporary return to coal and triggered massive subsidies to cushion energy inflation. In developing economies, climate finance pledges remain unmet, leaving governments torn between clean energy ambitions and immediate development needs.

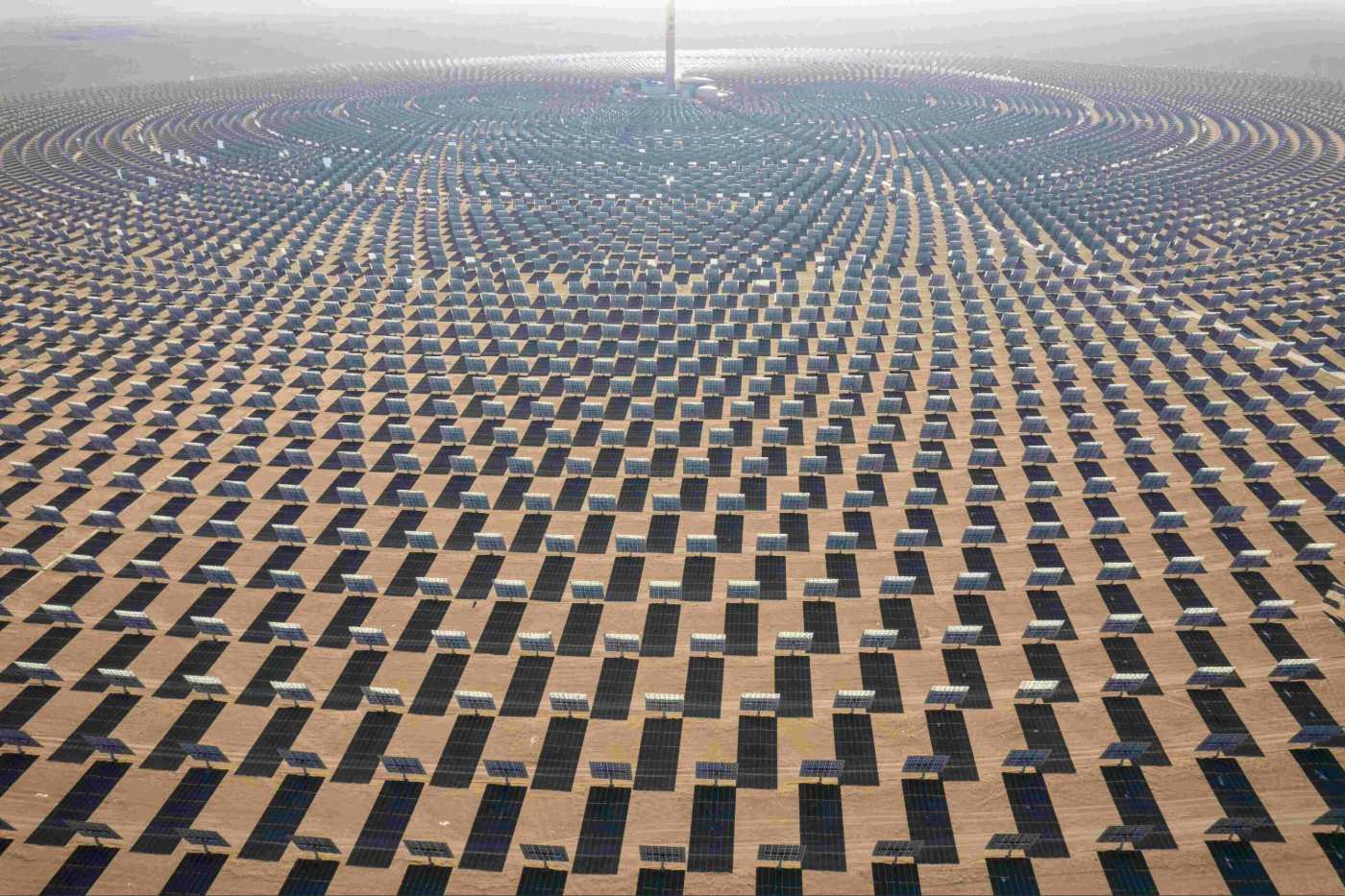

Geopolitically, the shift has been even more dramatic. Energy has emerged once more as a strategic asset. The US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) channeled hundreds of billions of dollars into domestic clean energy, triggering concerns over green protectionism. China dominates global solar and battery supply chains, even as it continues to produce coal-fired power to ensure economic stability. In the EU, the REPowerEU strategy seeks to accelerate renewables and end dependence on Russian fuels. In practice, it has reinforced national-level energy strategies, notably through bilateral gas deals, domestic subsidies, and fast-tracked local infrastructure.

The result is strategic fragmentation. Where once there was a sense of global coordination, today we see overlapping national priorities and competing industrial strategies. Supply chains are being redrawn, and energy alliances are shifting. These geopolitical shifts make the trilemma more localized and unpredictable for firms with international operations.

In this fractured landscape, companies can no longer assume energy will flow smoothly across borders, nor can they take policy stability for granted. Energy resilience and geopolitical literacy are fast becoming core business capabilities.

Electricity is harder than oil

For all the optimism around renewables, the energy transition comes with physical constraints, especially in infrastructure. Unlike fossil fuels, which can be stored in tanks, shipped globally, and priced through global markets, electricity is more like a local product. Electrons must travel through wires, and due to limitations in storage, electricity is produced, sold, and transported on demand.

Solar and wind production is intermittent, making the renewable energy system more complex and creating extra volatility if not carefully managed. Grid bottlenecks are a further obstacle to decarbonization. In many regions, connecting new solar or wind projects to the grid takes years, with permit delays, local opposition, and outdated infrastructure slowing progress.

This mismatch between ambition and physical capability creates new risks for businesses. A firm may want to decarbonize operations but discovers that the local energy system cannot reliably support electrification. Alternatively, it may invest in on-site renewables, only to face curtailment or regulatory barriers. These are not theoretical issues; they’re already happening in parts of Europe, the US, and Asia.

The contrast with fossil fuels is stark. Molecules like coal, oil, and gas can be traded, stored, and rerouted. They offer flexibility in a crisis, whereas electrons do not. Companies must prepare for a new kind of exposure as they lean in to electrification: how dependent they are on the energy system.

Audio available

Audio available

Audio available

Audio available