Why leaders should learn to value the boundary spanners

Entrepreneurial talent who work with other teams often run into trouble with their managers. Here are ways to get the most out of your ‘boundary spanners’...

Audio available

by Cyril Bouquet, Jean-Louis Barsoux, Michael R. Wade Published January 26, 2022 in Innovation • 10 min read •

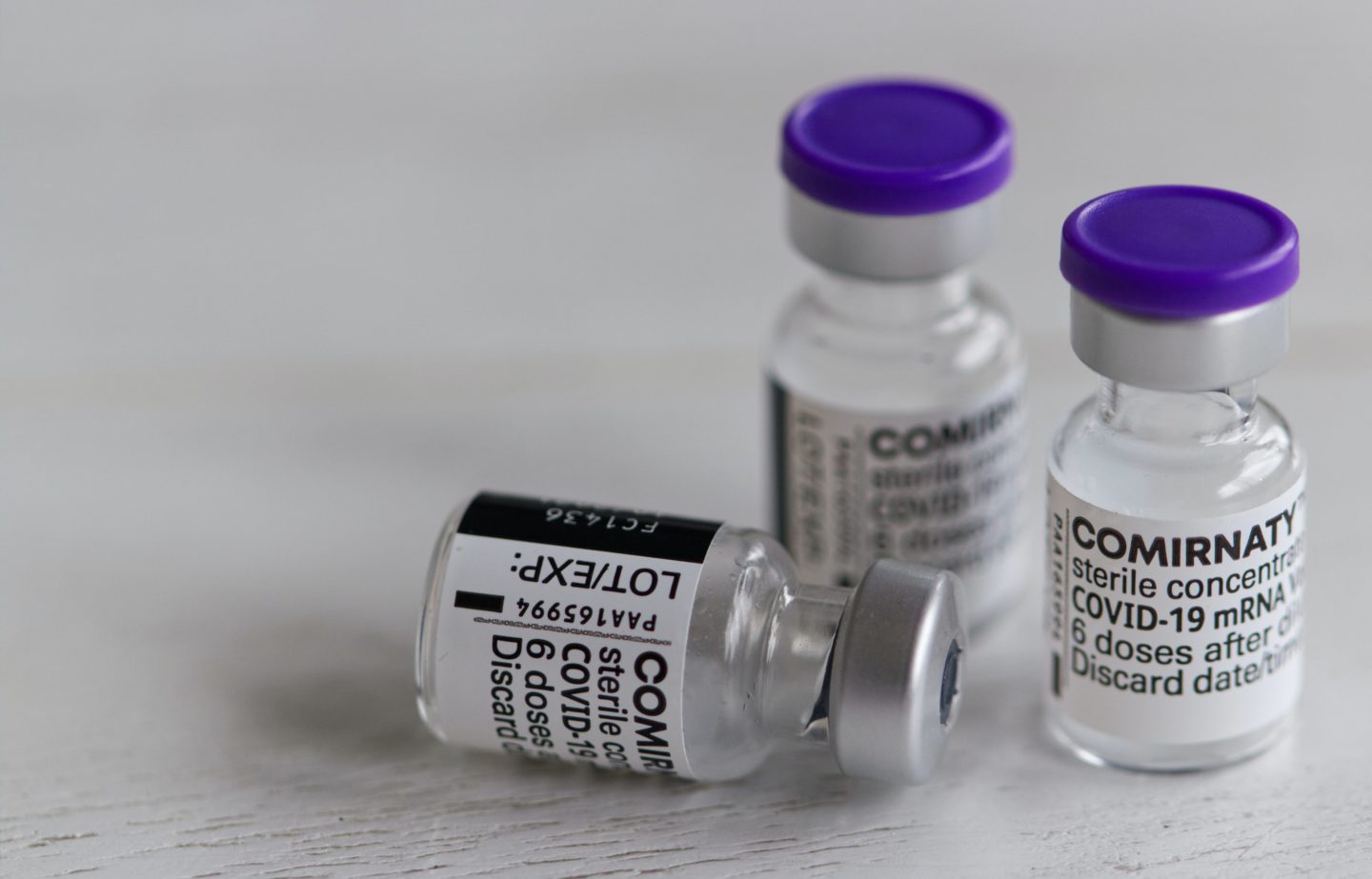

The story of BioNTech, the small biotech company that delivered the first US-approved coronavirus vaccine, is already the stuff of lore. Maintaining the pace, the pioneering German group has since revealed it has harnessed artificial intelligence to fast-track new vaccines to deal with Omicron and future COVID-19 variants; it has also announced a further partnership with pharma giant Pfizer to develop a new treatment for shingles.

BioNTech’s success is a tale of relentless innovation based on radically unorthodox thinking. Cancer researcher Özlem Türeci and her husband Uğur Şahin began by trying to find ways of harnessing the body’s immune system to attack tumors instead of fighting them with aggressive chemotherapy and radiation.

They set up their first venture, Ganymed, in 2001 to develop therapeutic antibodies, with Türeci as chief executive and Şahin heading research. The couple sold Ganymed 15 years later to a Japanese pharmaceuticals group and used the proceeds to turbocharge BioNTech, their second start-up.

At BioNTech, the pair investigated using messenger RNA (mRNA) – a molecule that tells cells what proteins to make – to create a harmless replica of part of the pathogen that trains the immune system to defend itself. This time Türeci was chief medical officer, while Şahin took on the role of CEO.

Mainz, Germany where BioNTech is based, is hardly a hub for groundbreaking biotech research, let alone a rival to Boston or Silicon Valley. Nor was BioNTech an obvious candidate to win the race for the first US-approved coronavirus vaccine. And yet the couple’s agile thinking and end-to-end approach to innovation delivered a vaccine in record time.

Their success highlighted three critical shifts to boost the chances of radical innovation.

“We saw this as a duty. We [had] technologies and capabilities and skills in the company... which [made] us think that we [could] contribute. ”- Özlem Türeci (pictured with her husband Uğur Şahin)

The first shift requires snapping out of a default perspective and looking in new ways or from a fresh vantage point to notice what other people are missing and to make sense of it.

This is what the couple did over breakfast one weekend in January 2020, while discussing an article in The Lancet, the respected medical journal. The piece had nothing to do with cancer; it was about an outbreak of a mysterious respiratory disease sweeping through China’s Hubei province.

The study, which focused on the case of a family of six, indicated an alarming rate of transmission, but it was another detail that caught Şahin’s eye. “What was most concerning is that one of the family members had the virus and was virus-positive, but did not have symptoms,” he said in a Wall Street Journal podcast. Şahin was convinced that the surreptitious nature of the disease, allied to the intensity of global travel, meant the virus had probably already escaped China. And it was set to spread even faster than the study’s authors suspected. This was two months before the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic.

Discussing the problem, the couple saw a connection to their work on cancer. The same mRNA technology they had developed to train the body to attack cancer cells could, in theory, be used to get the immune system to produce antibodies against a virus.

Their experience in providing individualized treatments for cancer meant that they could probably develop a vaccine quickly. But there was no guarantee that the virus might be susceptible to a vaccine. And while the pair had a handful of cancer vaccines in clinical trials, no mRNA vaccine had ever been approved.

As the company’s chief medical officer, Türeci would need to interrupt two decades of cancer research to pursue a cure in another field. “We saw this as a duty,” Türeci told USA Today. “We [had] technologies and capabilities and skills in the company… which [made] us think that we [could] contribute.”

They agreed to divert their research efforts into finding a vaccine to fight coronavirus.

Having a bold idea is one thing; acting on it is another. A frequent blocker of radical innovation is the inability or unwillingness to adapt one’s approach to the challenge. For Türeci and Şahin, the big readjustment was the extraordinary change of pace.

Scientific research is typically a slow, deliberative process, where failures are expected and progress is often measured in years, sometimes decades. But the entrepreneurial duo had already evolved their practices away from that, in large part because of the applied nature of their research.

Türeci told the Financial Times: “We were forced when we started with personalized cancer trials to develop testing and manufacturing processes which were very fast, very agile, and very adaptable.”

Developing a COVID-19 vaccine raised that time pressure to a whole new level. In this race, each day gained could result in thousands of lives saved. Within hours of agreeing to switch their strategic focus, CEO Şahin secured the backing of Helmut Jeggle, Chair of BioNTech’s supervisory board, to combat a virus which was as yet undiagnosed in Germany.

Just two weeks earlier, Chinese researchers had released a genome of the virus. A key advantage of mRNA is that it enables researchers to produce multiple versions of the molecule within days, bypassing the lengthier process of having to create cell cultures. Şahin spent the rest of the weekend on his home computer designing the template for 10 possible coronavirus vaccines.

Returning to work on Monday, Şahin announced to the top team – and to BioNTech’s 1,000 employees – the decision to pivot. It was not an easy sell. First, he had to ask staff to stop using public transport. Then he asked key workers to cancel holidays and teams to organize their own coverage of 24/7 shifts. He impressed on everyone the importance of their mission, citing the impact of the Hong Kong flu that claimed an estimated four million lives in 1968–69. This was their chance to make a real difference.

To underline the shift in strategic focus and the sense of urgency, the top team named the effort Project Lightspeed – signaling the clear intention to develop a vaccine in months, not years.

We relentlessly pursued the principle of minimizing development times without skipping development steps or taking shortcuts- Uğur Şahin

Building on Şahin’s initial work, by early February BioNTech’s scientists had proposed 20 vaccine candidates. Many of them were designed to configure proteins resembling a piece of the distinctive spike of the coronavirus to elicit an immune response.

To press home this initial advantage, BioNTech reconfigured its processes. “We relentlessly pursued the principle of minimizing development times without skipping development steps or taking shortcuts,” Şahin told Business Insider. “The tasks that are normally approached sequentially in vaccine development were done in parallel.”

Türeci and Şahin adopted an approach to experimentation that optimized two seemingly contradictory qualities. It combined high focus and high flexibility – keeping their options open for as long as possible. By mid-April, BioNTech scientists had eliminated 16 of the vaccine candidates, leaving the four most promising ones.

The company had contacted the German regulators from the start to prepare them for the new type of vaccine and to try to ensure fast-track approval for Phase 1 and 2 clinical trials. A process that normally took the authorities three months was completed in just three days.

BioNTech decided to test all four remaining vaccine candidates concurrently. The company also took the risk of organizing itself for success. In a New York Times podcast, Türeci explained: “We basically prepared the more advanced trials in parallel to conducting the Phase 1 trial, at risk of not having a candidate, which would then go into Phase 3.”

By now BioNTech had expanded its production facilities, with assistance from the German government, but Şahin knew his company would need help not just to produce a vaccine, but also to conduct large-scale clinical trials and navigate international regulatory hurdles.

He had taken the precaution of contacting Pfizer’s head of vaccine research, Kathrin Jansen, as early as February. By mid-March, the two companies had agreed to collaborate, meaning their joint venture was able to launch simultaneous clinical trials in Germany and the United States.

A third barrier to breakthrough innovation is underestimating the gap between a working solution and a breakthrough solution. In innovation models, this final phase is often labeled execution, implementation, or launch; however, these labels don’t do justice to the agility and unorthodox thinking required to transform the ecosystem and adapt one’s message to the needs of different stakeholders.

As dedicated researchers, Türeci and Şahin could easily have neglected the challenges of getting the product to market, preferring to focus on the science instead, but they were all too conscious of that risk. Asked whether logistical, purchasing, and supply chain concerns felt like an unwelcome distraction from the research, Türeci told Der Spiegel: “That’s just part of the deal when you are trying to bring something brand new from the laboratory to the patient. You have to be humble and take care of all those things that you always thought other people should handle.

“You learn to see things like production, storage, cooling, and transportation as an extension of scientific innovation. Here, too, new solutions are required for problems that have never been encountered before.”

Distribution was a case in point. While mRNA vaccines benefit from accelerated design, they have one critical disadvantage: they need to be stored at −70°C (−94°F). This posed a huge storage and transportation challenge.

Again, Türeci and Şahin did not wait for the vaccines to be ready to line up an array of partners, this time with expertise in cold chain management. For example, within weeks of switching direction, BioNTech alerted the specialist glass manufacturer Schott that it would need to ramp up production of vials capable of resisting temperatures as low as −80°C (−112°F).

By March 2020, BioNTech had contacted other key players in Germany: Binder, a manufacturer of “super freezers” to chill coronaviruses used in lab research; and Va-Q-Tec, a producer of shipping containers and boxes with an ultra-cool function. BioNTech also urged freight services at Frankfurt airport to invest in hi-tech refrigerated “dollies” to transport the vaccines from hangars to planes.

Alongside clinical development, BioNTech had to mobilize a new network of collaborators. Ultimately, it was this smart alignment of multiple partners ahead of time that made the difference.

On 18 November, 2020, less than10 months after first noticing the problem, BioNTech and its partner, Pfizer, were able to announce a successful result with a 95% efficacy against the virus.

Having achieved their coronavirus target, Türeci and Şahin now intend to resume their original goal of developing a new tool against cancer.

But their COVID-19 breakthrough has been a game-changer. As the first mRNA vaccine to be approved, their achievement holds an even bigger promise. It opens the door to a new, disruptive technology that could revolutionize medical research. Şahin told the Financial Times: “Dozens of mRNA cancer therapies, immunizations for rare diseases, and treatments for HIV and tuberculosis could now be fast-tracked.”

A scientific couple has probably not been so celebrated worldwide since Pierre and Marie Curie, who won the Nobel prize. Although Özlem Türeci and Uğur Şahin have not yet won theirs, their breakthroughs may yet be recognized when mRNA technology reveals its full impact.

Professor of Innovation and Strategy at IMD

Cyril Bouquet is Director of the Innovation in Action program, co-Director of the TransformTECH program and the Business Creativity and Innovation Sprint. As an IMD professor, his research has gained significant recognition in the field. He helps organizations reinvent themselves by letting their top executives explore the future they want to create together.

Research Professor at IMD

Jean-Louis Barsoux helps organizations, teams, and individuals change and reinvent themselves. He was educated in France and the UK, and holds a PhD in comparative management from Loughborough University in England. His doctorate provided the foundation for the book French Management: Elitism in Action (with Peter Lawrence) and a Harvard Business Review article entitled The Making of French Managers.

TONOMUS Professor of Strategy and Digital

Michael R Wade is TONOMUS Professor of Strategy and Digital at IMD and Director of the TONOMUS Global Center for Digital and AI Transformation. He directs a number of open programs such as Leading Digital and AI Transformation, Digital Transformation for Boards, Leading Digital Execution, Digital Transformation Sprint, Digital Transformation in Practice, Business Creativity and Innovation Sprint. He has written 10 books, hundreds of articles, and hosted popular management podcasts including Mike & Amit Talk Tech. In 2021, he was inducted into the Swiss Digital Shapers Hall of Fame.

July 3, 2025 • by Eric Quintane in Audio articles

Entrepreneurial talent who work with other teams often run into trouble with their managers. Here are ways to get the most out of your ‘boundary spanners’...

Audio available

Audio available

June 24, 2025 • by Jerry Davis in Audio articles

The tech broligarchs have invested heavily in Donald Trump but are not getting the payback they bargained for. Do big business and the markets still shape US government policy, or is the...

Audio available

Audio available

June 19, 2025 • by David Bach, Richard Baldwin, Simon J. Evenett in Audio articles

As governments lock horns in our increasingly multipolar world, long-held assumptions are being upended. Forward-looking executives realize the next phase of globalization necessitates novel approaches....

Audio available

Audio available

June 2, 2025 • by George Kohlrieser in Audio articles

Leadership Honesty and courage: building on the cornerstones of trust by George Kohlrieser Published 17 April 2025 in Leadership • 5 min read DownloadSave Trust is the bedrock of effective leadership. It...

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience