The twin pillars of strategic climate response

Against this backdrop, climate leadership is a challenge on two fronts: reducing emissions at scale and building resilience to the disruptions already underway. Yet, too many companies treat these as separate conversations. The ones that will define their industries over the next decade are integrating both, designing mitigation and adaptation strategies to reshape their business models from the inside out.

Mitigation: rebuilding the business core

For a growing number of industrial leaders, mitigation is no longer about marginal improvements but strategic reinvention, retooling the core business for a low-carbon economy.

Two companies stand out as examples: Siemens and Schneider Electric. Longtime rivals in electrification and industrial automation, they are now in what one author of this article calls “the Coca-Cola wars of sustainability”. Each is pushing the other to go further and faster in decarbonizing not only their operations, but those of their customers.

Siemens has embedded an internal carbon price for investment decisions and rolled out digital twin technology to help manufacturers simulate energy impacts before making changes on the shop floor. Schneider has built a $40bn business helping clients reduce their emissions, turning sustainability into a top-line driver rather than a compliance cost. Their competition is raising the bar across sectors: from smart buildings and low-voltage grids to factory automation and energy-as-a-service models. This is what true mitigation leadership looks like, not offsetting emissions, but reengineering value creation for a net-zero future.

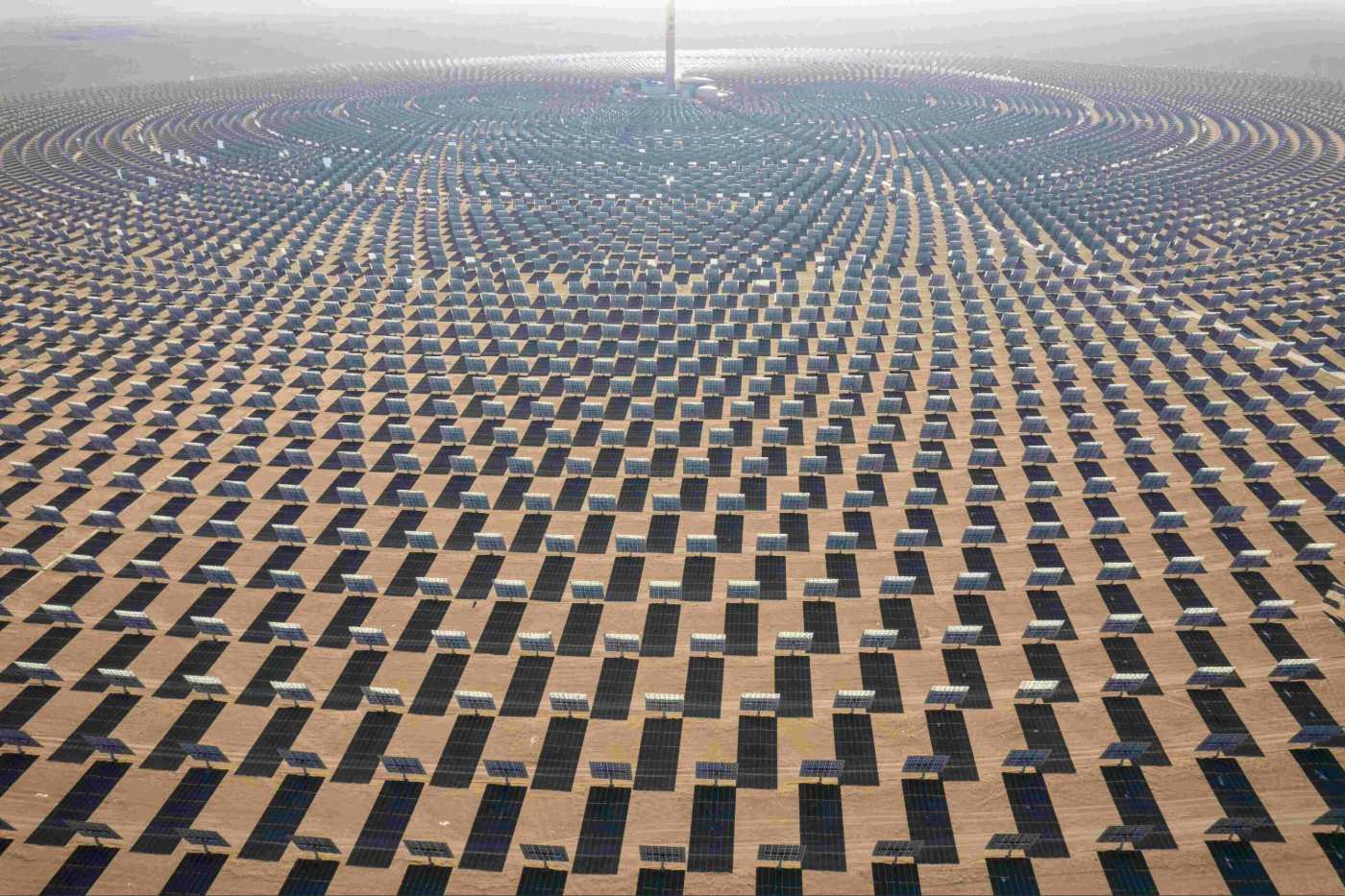

In the energy sector, European utility RWE is making a comparable shift. Once one of Europe’s largest coal generators, RWE is now among the continent’s fastest-growing renewable energy developers. It plans to invest €55bn ($64bn) in green energy by 2030 – doubling down on the reality that future profitability hinges on decarbonized capacity. Ørsted’s pivot from fossil fuels to offshore wind is well documented, but it is worth including here. The point is to recognize the pattern: mitigation leaders aren’t tweaking, they’re transforming.

Also often overlooked is the vast and rapidly expanding landscape of transition opportunities between climate-tech pioneers and traditional corporates. Across industries, opportunities are emerging to retrofit existing infrastructure, electrify fleets, decarbonize heat, embed circular design into product lifecycles, and use AI to drive operational efficiency and resource optimization.

In real estate, developers are integrating low-carbon concrete and smart grid connectivity. In agriculture, startups are leveraging biochar and precision fermentation to reduce methane emissions and regenerate soil. In logistics, companies are using AI to optimize shipping routes and electrify last-mile delivery. Industrial firms are investing in hydrogen-powered heat processes, while retailers are reimagining packaging, logistics, and customer engagement with carbon and material footprints in mind.

The next wave of mitigation leaders will emerge not only from clean tech but from every sector willing to reimagine how it operates.

Adaptation: the innovation imperative (and its limits)

In contrast, adaptation is about survival and preparing for climate shocks that no amount of mitigation can avoid. We’re already suffering from the consequences of our inaction.

Take Climeworks, the Swiss startup leading the charge in direct air capture (DAC), the process of removing CO₂ directly from the atmosphere. The technology is promising, potentially essential. It’s also expensive, energy-intensive, and struggling to move from lab-scale to economic viability.

This reflects a broader truth: we cannot offset our way out of this crisis. Adaptation technologies are crucial, but they are not a substitute for emissions cuts. They’re a hedge; a safety net. In sectors such as insurance, food, and infrastructure, they are rapidly becoming a lifeline. Yet adaptation extends far beyond carbon removal. It includes physical infrastructure that can withstand extreme weather, supply chains that can reroute in real time, and cities that can cool, drain, and protect faster than nature disrupts.

From urban flood defenses in Bangkok to predictive crop management in sub-Saharan Africa, adaptation is becoming a core operating requirement. It’s also a space ripe for innovation, but one that demands realism. The financial returns may be longer, the payoff harder to measure, but the risk of neglecting it is existential.

Opportunities are emerging rapidly. Businesses are investing in climate-resilient agriculture, including drought-tolerant crops, sensor-based irrigation, and AI-driven yield prediction. Utilities are exploring distributed energy networks to preserve continuity during grid disruptions caused by storms or heatwaves. Apparel and food producers are localizing and diversifying sourcing to insulate themselves from climate-related supply volatility. Cities and developers are embedding adaptation into planning codes, with green roofs, permeable pavements, and heat-resilient design becoming standard practice in leading markets.

Even financial services are innovating: banks and insurers are offering new climate-linked products and rethinking asset valuations based on long-term exposure to climate risk. Human capital strategies are shifting, too. Companies are asking: how do we keep workers safe in high-heat environments? How do we address mental health and migration stress caused by extreme climate events? These are no longer peripheral questions; they are business continuity issues.

Adaptation is not an act of surrender. It is a strategic investment in operational integrity, community stability, and long-term viability. The businesses that thrive will be those that see resilience not as a cost, but as a core competency.

The most mature companies aren’t choosing mitigation over adaptation, or vice versa. They’re building dual-track strategies that do both, often within the same capex cycle or innovation budget. Mitigation without adaptation is a delayed failure, and adaptation without mitigation is a slow surrender.

The defining leadership question of our time

As the energy transition accelerates, so does the temptation to retreat. Faced with inflation, geopolitical instability, shifting subsidies, and political backlash, you might be tempted to quietly soften targets, delay investments, or deprioritize sustainability in favor of near-term stability. You may be hoping to coast until clarity returns, or you may be simply overwhelmed. In reality, this kind of inaction is a decision to let others define the rules of the game. What feels like caution today will be seen as complacency tomorrow. Those who step back will find themselves locked out of markets, talent, capital, and influence.

One question towers above the noise: are you preparing your business to thrive in a world remade by energy, technology, and climate risk, or are you optimizing for a version of the economy that no longer exists? As you face up to that question, consider these critical trade-offs:

- Do we commit early, or wait for certainty? Leaders who act early are already capturing scarce materials, influencing standards, and earning reputational trust. Those who delay risk higher costs, shrinking influence, and fading relevance.

- Do we shape the transition, or adapt to it? Leaders like Schneider Electric and Siemens are not just adjusting; they’re setting expectations across industries. Whether through product design, ecosystem-building, or market-making, shaping the transition creates the conditions others must follow.

- Do we go it alone, or build coalitions? No single company can deliver net zero alone. Forward-looking firms are forming cross-sector alliances to build new infrastructure, unlock financing, and scale innovation. In a fragmented world, the winners will align interests, not just assets.

- Do we optimize for now, or invest in what’s next? absorbing short-term noise to secure long-term strategic control.

In the coming decade, climate performance will become indistinguishable from financial performance. Leadership won’t be measured by how well you comply but by how clearly you chart direction, how bravely you invest ahead of the curve, and how quickly your organization can adapt to shocks without losing sight of its long-term mission.

As you face your next board meeting, quarterly review, or investor Q&A, don’t just ask yourself, “What are we doing about sustainability, energy, or climate?” Ask, “Are we shaping the future, or will we be shaped by those who do?”

Audio available

Audio available

Audio available

Audio available