Empowerment and purpose: How UK fintech Wise ensures its staff want to stay

Freedom to operate and inspiring purpose are critical factors in the attraction and retention of talent, argues Wise CPO Isabel Naidoo....

by Tania Lennon Published February 2, 2024 in Talent • 9 min read

Despite a concerted focus on talent management over the past 25 years, the gap between what talent organizations need and what they can find, mobilize, and engage appears to be widening – with alarm bells sounding loudly about a lack of skills and capabilities to support sustained organizational success.

A significant contributor to this is the disconnect between traditional forms of job analysis and the dynamic context. Deconstructing roles carefully into component parts of knowledge, skills, and abilities, and then carefully matching individuals to role requirements – either for selection or succession – is a robust process. Yet this process has been stretched to breaking point by three key shifts in the world of work.

Rapid changes in technology, the digitalization of work, an ever-changing commercial context, and the confluence of social, environmental, and political factors – the world of work has become a rollercoaster of twists and turns that require high levels of adaptability and rapid shifts in the skills and capabilities that individuals bring to their roles.

Complexity in the work environment necessitates higher rates of cross-functional collaboration. Networks for co-creation and cooperation increasingly span organizations, providing a holistic and coherent approach to solving challenging and multi-faceted problems. The driver of performance in this context is unlikely to be a lone heroic.

The discipline of the well-constructed job description is designed to provide a consistent basis for talent matching to ensure fairness, efficiency, and equity. In practice, the same job in different contexts can have very different requirements, even within the same organization. For example, the GM of a pharmaceutical company in Brazil is likely to require significantly different skills and capabilities to the GM in South Korea or Canada. Jobs are shaped by the systems, stakeholders, and regulatory environments in which they operate.

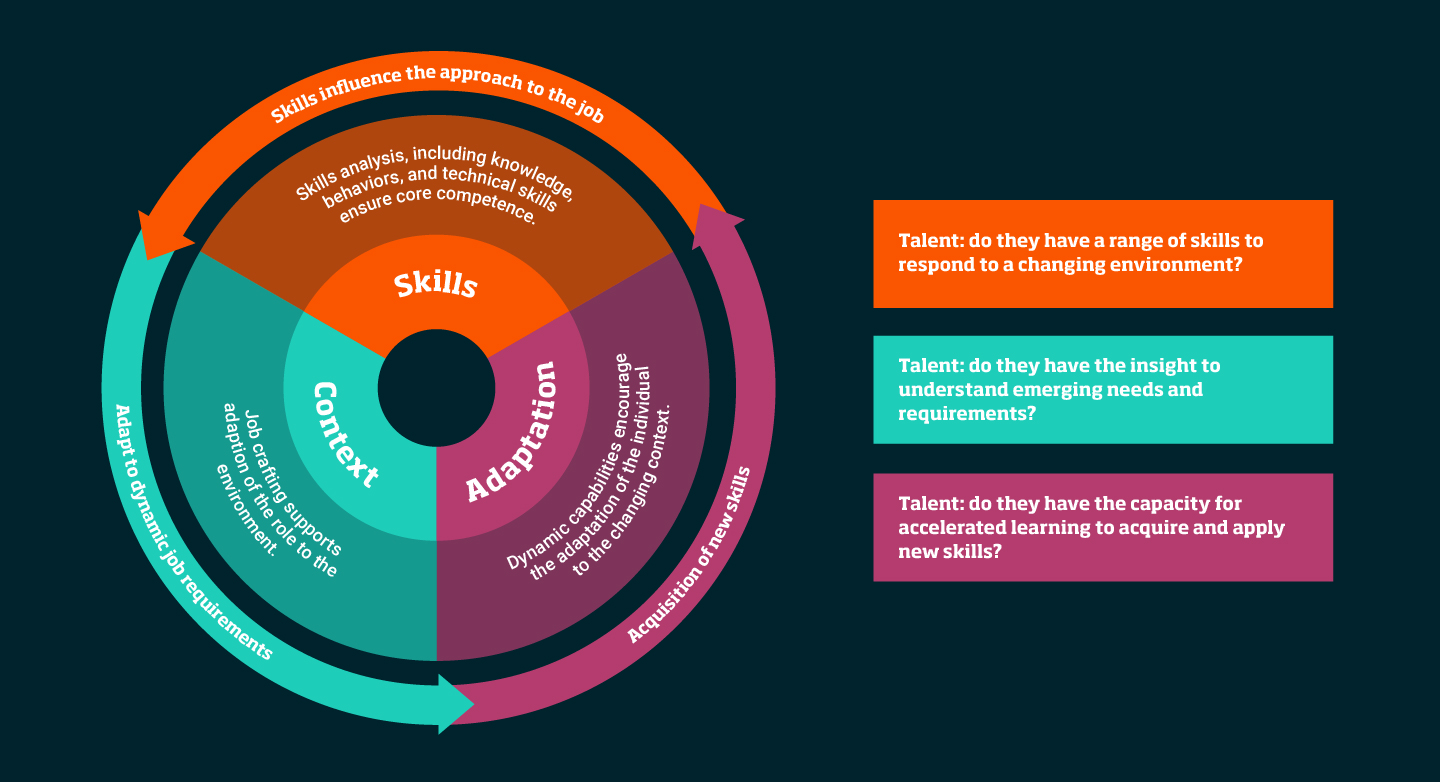

So, in this dynamic, interconnected, and heterogeneous context, how do you define jobs to better select, identify, and develop the talent needed to support performance? Three approaches to consider are skills-based organizations, job crafting, and dynamic capabilities.

The idea underpinning the skills-based approach to looking at jobs is to break them down into their component parts and map the observable and measurable skills necessary for a job, including behavioral characteristics, technical skills, and knowledge (Peregrin, 2014). This has two advantages. Firstly, it encourages organizations and managers to look beyond education alone to consider other sources of evidence of acquired skills. This chimes with recent headlines about organizations no longer requiring tertiary education as part of their talent selection process. Education remains a tangible and robust source of evidence of some key skills that should not be readily discarded, but it is not the only source of information that should be considered. Secondly, the skills-based approach supports greater mobility of talent between roles as it provides a lens through which to view the relevant skills that span functional or expertise areas.

However, a skills-based approach to job and talent matching comes with challenges. Firstly, it requires sophisticated job- and person-analysis skills. Secondly, it requires a high level of coordination and administration to map, capture, update, and apply relevant skills to facilitate the vision of an organizational talent marketplace and fluidity of resources across projects and roles. Thirdly, while it offers more agility in leveraging talent across organizations by moving talent where it is needed more quickly, it may overlook the important role that work plays in contributing to an individual’s identity through a sense of purpose and competence and through the social connections that they forge.

Job crafting occurs when individuals shape the characteristics of their jobs. This can be driven by the context, where individuals adapt to the specific demands of their work environment, and by the individual, as they adapt the role to make it more enjoyable, more challenging, and a better fit with other aspects of their life. As defined by Wrzesniewski and Dutton (2001), job crafting can take three forms, with job incumbents changing the number or type of activities (task), the people and stakeholders they engage with at work (relational) and the way they think about the job and how it provides meaning (cognitive).

“Reports of the death of the job may not have been greatly exaggerated – but fresh thinking can support organizations to be better equipped to get the talent they need to sustain success.”

Job crafting has a positive impact on performance in two ways. Directly, it facilitates adaptation of the job to the local context, resulting in better work outcomes. Indirectly, job crafting enhances job satisfaction and well-being, supporting each individual to manage the rigors of their role.

The challenge with job crafting lies in its application. Organizations can find it difficult to maintain equity in compensation as the level of divergence between roles increases. They also report that individuals can find it difficult to fully harness the promise of job crafting without support and training to help them think differently about their role. Training is also vital to ensure that job crafting activities are aligned with the broader strategic purpose, priorities, and culture of the organization which provide essential ‘glue’ to enable alignment around the most important outcomes from the job.

Dynamic capabilities are the result of organizations cultivating and strengthening the ability of employees to recognize, acquire, and apply new skills. Unlike skills-based organizations, which focus on acquired skills, dynamic capabilities focus on the acquisition and application of skills. According to researchers such as Rosing, Frese, and Bausch (2011), individuals who succeed in acquiring, applying, and adapting their approach to different work challenges possess three key attributes.

First, they have the cognitive flexibility to accurately discern the requirements for success, including the skills required. Second, they demonstrate strategic process flexibility, choosing from a broad toolkit of knowledge, expertise, and capabilities to choose the one that is most likely to deliver results rather than always relying on tried and tested methodologies that have driven success in the past. Third, they have the behavioral flexibility to try out new approaches and adapt their behaviors and skills to address the new and emergent demands of the situation.

Accelerate your career with strategic business capabilities and transformative leadership skills.

Embedding dynamic capabilities to enable faster acquisition and deployment of skills is not easy. At an organizational level, it requires the company to be adaptable and externally facing. There must be a clear sense of purpose and identity that provides an enduring sense of connection, but not a culture that is so strong it acts as a force for stability and continuity rather than change. Practically, dynamic capabilities necessitate space to practice. Most organizations have embedded a rich seam of opportunities for learning, whether attending a program or engaging with learning content. Yet many struggle to provide the conditions to enable individuals to move from conscious incompetence to conscious competence as they start to apply their learning in practice. This requires a carefully constructed ecosystem around individuals to cultivate what is known as the ‘transfer environment’, which is a key driver of the ROI that organizations derive from learning investments.

Each of these three approaches has a valuable contribution to make to enable leaders to start thinking differently about jobs and talent. A talent-centric approach to supporting organizational performance can look at jobs through three lenses:

Taking a robust approach to defining the skills required in jobs and the skills that individuals bring to roles while ensuring new skills are recognized and integrated.

Actively encouraging and supporting individuals to craft roles to address the needs of the specific context and create the conditions to optimize their performance and well-being while ensuring alignment around common goals.

enabling accelerated learning for the acquisition of new skills and cultivating an organizational environment that supports the activation of new skills in practice while maintaining an external orientation focusing on ‘what’s next.’

Drawing on all three approaches acknowledges that shaping jobs is a connected, dynamic, and continuous process with people as the architects of the process – not the recipients. This combination offers a potent recipe for enhancing performance through people by thinking about jobs in a way that is congruent with the challenges of the dynamic environment. Reports of the death of the job may not have been greatly exaggerated – but fresh thinking can support organizations to be better equipped to get the talent they need to sustain success.

Executive Director of the Strategic Talent Development initiative

Tania Lennon leads the Strategic Talent team for IMD. She is an expert on future-ready talent development, including innovative assessment methods to maximize the impact of talent development on individual and organizational performance. Lennon is a “pracademic”, blending a strong research orientation with evidence-based practice in talent development and assessment.

March 4, 2026 in Talent

Freedom to operate and inspiring purpose are critical factors in the attraction and retention of talent, argues Wise CPO Isabel Naidoo....

February 19, 2026 • by Robert Hooijberg in Talent

Cutting entry-level roles may save costs today, but it endangers the development of future leaders and the skills organizations will urgently need....

February 16, 2026 • by Zhike Lei in Talent

Some of China’s most profitable companies have thrived by piling pressure on workers – sometimes with tragic results. Zhike Lei outlines how multinationals can design work that avoids burnout and exploitation. ...

February 5, 2026 • by Katharina Lange in Talent

Entry-level roles give new recruits an opportunity to develop intuition and judgment. But a lack of humility could be stunting the development of future leaders, argues IMD’s Katharina Lange. ...

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience