The field study did not explain why such behavior occurs, so to address this, we designed a second study involving 410 managers who participated in a scenario-based online experiment. Each was randomly assigned to read a vignette describing a fictional employee. The scenarios varied in two dimensions: whether the employee engaged in boundary spanning and whether they sought advice from their supervisor. Managers were asked to respond to statements measuring their perceptions and intended behaviors. We assessed whether managers felt they had lost control of their team’s image and decision-making, whether they attributed political or malicious motives to the employee’s behavior, or whether they intended to respond with undermining behavior.

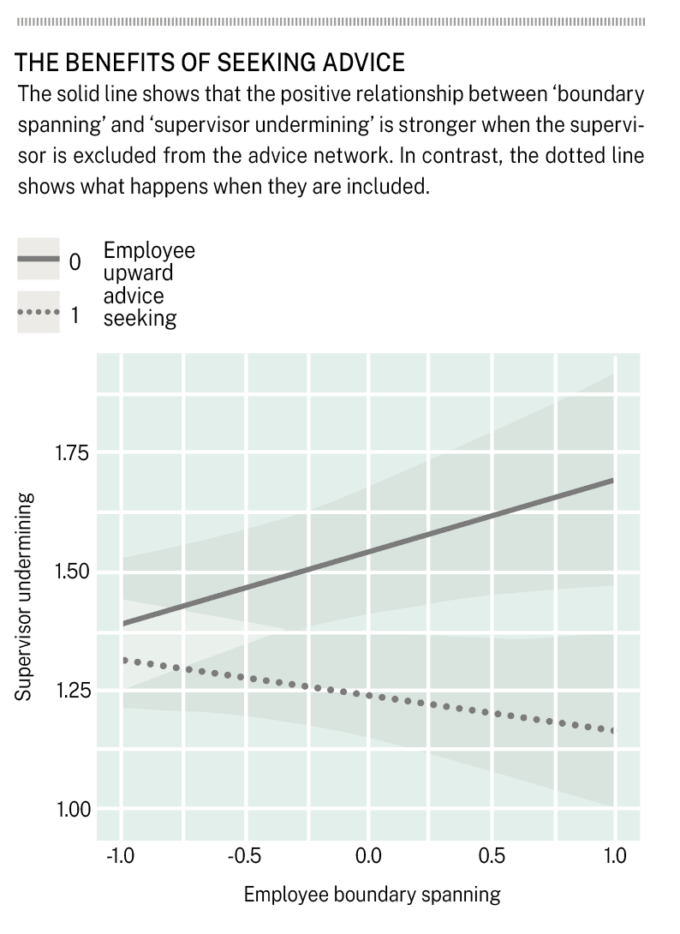

The data revealed that managers who read about an employee engaging in boundary spanning without seeking their advice reported a greater sense of losing control over their team. They were likelier to attribute harmful intent, such as political maneuvering or disloyalty, to the employee. Managers were especially likely to consider undermining their employees when they felt both a loss of control and believed the employee had acted with questionable intent.

These results suggest that managers’ reactions are not purely emotional or impulsive but are shaped by a structured psychological process. When managers are excluded from collaborative decisions or cross-team interactions, they often interpret these actions through the lens of territoriality. They feel they are losing influence over how their team is represented and how decisions are made. If they believe the employee’s motives are self-serving, they retreat into defense mode and take steps to reassert their authority, draw boundaries, and punish perceived disloyalty.

Together, the studies reveal a consistent pattern: when employees reach outside their team for advice without involving their manager, some supervisors respond with defensiveness and even retaliation. But these reactions aren’t arbitrary. They follow a recognizable psychological logic rooted in how managers interpret threats to their authority, identity, and control.

Why managers react defensively

It may seem puzzling that a leader would resist behavior that benefits their teams and organization. Cross-silo collaboration often leads to new ideas, better decisions, and increased learning. Yet our findings show that boundary-spanning behavior can trigger specific psychological responses in managers, particularly when they feel left out. These reactions reflect concerns about authority, alignment, and loyalty. Boundary spanning can be ambiguous for a manager: it can be seen as proactive and prosocial or political and disloyal. The way it is perceived determines how a manager responds. Three mechanisms help explain this dynamic:

1. Perceived loss of control

Many managers view themselves as responsible for their team’s strategic direction and external image. When employees bypass them to collaborate across teams, managers may feel that their influence over key decisions and narratives is slipping away. This perceived loss of control over team boundaries, especially in hierarchies where managerial oversight is emphasized, can trigger defensive behaviors intended to assert authority.

2. Attribution of harmful intent

Managers don’t just respond to what employees do; they respond to what they think it means. If an employee’s boundary-spanning behavior is interpreted as genuine curiosity or collaborative effort, managers may welcome it. But if the same behavior is seen as self-serving, politically motivated, or designed to bypass authority, it becomes a perceived threat. Our study shows that this attribution of harmful intent is a key trigger of undermining responses.

3. Absence of affirmation through upward advice-seeking

When employees seek advice from their supervisor, it signals deference, inclusion, and alignment. This simple act reassures the manager that they remain valued and consulted. In our study, this behavior significantly reduced the likelihood of defensive responses. When that advice element was absent, supervisors were more likely to feel bypassed and react negatively. It’s not just what employees do outside the team; it’s whether they maintain the symbolic link inside it.

These dynamics don’t just affect a single interaction. Over time, they can influence how employees approach collaboration, especially when similar signals repeat across different teams or contexts. Let’s look at what can happen when such reactions become a pattern.

Audio available

Audio available