Specialists and generalists both must handle this uncertainty and these biases. The specialist approach seeks to structure the haystack by building sub-investment universes in which each piece of straw is familiar to the specialist VC. Specialists hypothesize that you can master investment chaos and uncertainty if you focus.

But what does it mean to specialize in focused universes? We begin with a naïve categorization of the investment universe into geographies and industries. A specialist approach might be to focus on early-stage startups of the Swiss ecosystem that are active in the life-science sector. A VC may have developed a track record in detecting promising startups from these categories and leading them to a successful exit. This involves experience in recognizing early-stage potential – a process that is less numbers-driven and more about pattern recognition – and foreseeing team dynamics in novel roles as well as environments. The VC will have a local network with the best universities, research institutes, startup hubs, investment banks, lawyers, or corporates in that specific industry and region. The industry specialist will have acquired a proficient understanding of decision-makers, regulation, and market structures. He or she understands product life cycles and common obstacles in go-to-market campaigns in that field.

While these characteristics are convincing and – beyond a doubt – valuable assets for every venture capitalist, empirical evidence is rather against specialization. Instead, it reveals that diversification outperforms specialist funds.

The case for diversification

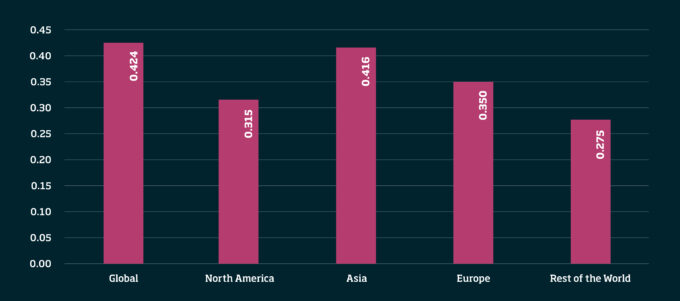

One of this article’s authors (Oender Boyman), analyzed data from the CEPRES database for the period 1980-2023 covering 1,840 funds and 28,452 deals that are analyzed for the effects of diversification regarding industry and geography.

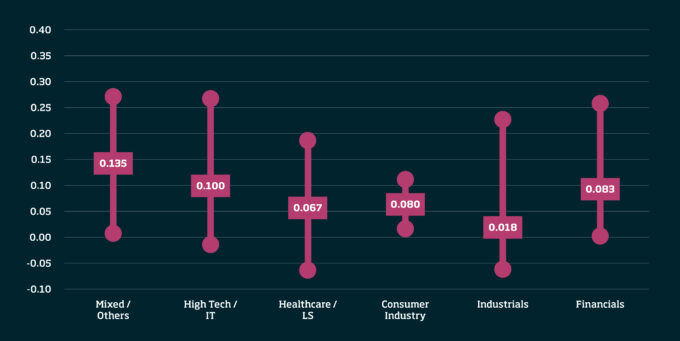

The results for industry diversification revealed that the internal rates of return (IRRs), serving as a measure of profitability, are highest for mixed funds with a median IRR of 13.5%. This gave a premium of 3.5% relative to the focused high-tech/IT industry funds.