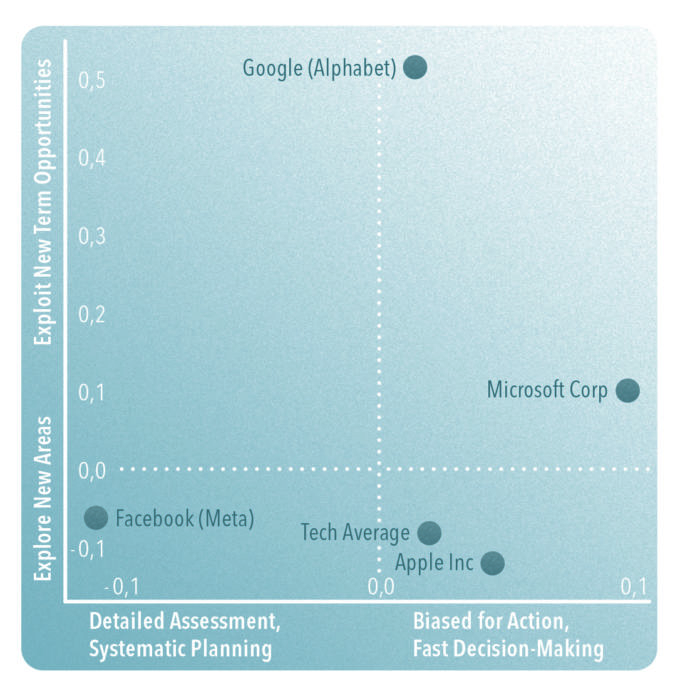

The implication here is when the usage requirement becomes exceedingly complicated, a company needs to partner with many others to deliver useful solutions. To do so, it needs to behave like a trusted partner or at least a benign giant. Apple’s notoriously closed approach could mean that it might miss out on a broad-based adoption in the enterprise sector. But this way of working can also be a strength, especially when the product remains novel and user experience remains unstable.

Remember that when Google Glass was released in 2013, Google touted the benefits of augmented reality to the masses. Priced at a premium of $1,500, the product was pitted against other top-end smartphones. Consumers naturally thought they would see information of all kinds with their gaze fixed upon anything and be able to pull that information from sources like Twitter, Facebook, and Wikipedia. When futurist Robert Scoble brought home the prized item, his wife asked eagerly: “Can I look at someone and see something about them?”

Predictably, Google Glass fell short of all expectations. The technology wasn’t ready yet, not even for Google. What this early example illustrates is for a new technology to take off, market demand is driven by its relative performance in relation to existing alternatives. Unless the immersive experience delivered by a headset becomes compelling enough, the metaverse has no use case. This doesn’t mean the next version of the internet is not arriving. It doesn’t mean tomorrow’s cyberspace can’t be immersive, 3D, and all folded together. It doesn’t mean that disparate websites and online services and NFTs and cryptos can’t come under one roof. It just means that won’t come in the current form of a headset that straps around your skull.

The late Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen, who coined the term “disruptive innovation,” once explained the imperative of such vertical integration. When the product was still “not good enough”, which is the current state of metaverse, performance is driven by integrated architecture. Like that of Tesla, which also packs batteries, writes firmware, and builds charging stations, in addition to developing its own electric vehicle. Like that of the smartphone in its nascent stage some 15 years ago, when it was pioneered by Apple. Only when a product becomes “good enough” does modular architecture become more effective. This is when companies can specialize in a smaller scope of activities. Some make software, some makes hardware, and still others make third-party applications. This parallel effort delivers greater speed of innovation with lower cost. But it requires a standard that’s already proven to work.

So if you want to predict the winner, you can bet on the one that integrates firm activities to solve difficult problems. For a product that is novel and new, problem solving cannot be outsourced yet. It requires the leaders and employees of an organization to wrap their heads around all the nuances. To do it right, they need to do it themselves.

Audio available

Audio available