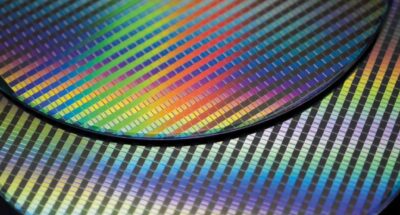

Europe needs Chips Act 2.0 to compete in digital race

Former French finance minister Bruno Le Maire says Europe needs to act urgently to secure its supply of semiconductors or face relegation to the global slow lane. ...

Audio available

by Cyril Bouquet, Alexis Georgacopoulos Published June 21, 2024 in Creativity • 9 min read

The Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama created 'The Spirits of the Pumpkins Descended from the Heavens', a typically dotty work. Image: Alamy

When Steven Sasson proposed a digital – filmless – camera to Kodak, the company’s leaders failed to see how valuable and disruptive it would become because their business model relied on selling film. They also did not see that concerns about image quality in early iterations would evaporate as the technology evolved. Then again, they didn’t see the mobile phone – and its in-built camera – coming either. When James Dyson proposed a bagless vacuum cleaner, the vacuum cleaner industry rejected him because of its dependency on revenue from replacement bags.

It might be unfair to look back with hindsight and find fault with those who missed out on a big break. Why would anyone ever want to cannibalize their existing business? Aside from change being the only constant, great innovators – and leaders – see things coming that most of their peers don’t. Their creativity and understanding of different perspectives, trends, and experiences generate a vision that rewrites the rules. We could say that innovators like Sasson, Dyson, or Steve Jobs are the artists of industry, joining the dots to reframe reality in a way that no one else can imagine.

Why don’t more companies imbibe more of this artistic spirit? Why do we often stifle – or just pay lip service to – creative thinking and design-led approaches? Shouldn’t every company take the hint from Apple’s runaway success and become a design-first company, too? Shouldn’t everyone have a chief design officer or a chief creative officer?

We’re probably all tired of hearing that today’s world is fiendishly uncertain and complex and becoming ever more so; that unprecedented disruption means hard-earned skills and expensively developed technologies are vital one day but irrelevant the next; that digital evolution and climate change demand a wholesale rethink of business models and society; and that our businesses and leaders have to adapt, like hyperactive chameleons, at increasing rates of acceleration just to survive, let alone compete or win.

The advice in response from management experts is that these treacherous, complex environments require “creative” solutions, co-creation with a greater diversity of partners, orchestrated by leaders and teams with highly refined soft skills who are “agile”, “authentic”, “entrepreneurial” – and, well, more creative. But what does this mean in practice? And how can we turn it into meaningful action that makes a difference? There are countless models, exercises, and frameworks to help executives adjust to these demands, but these can feel piecemeal. We believe something more radical is needed – a reframing of organizations and leadership through the lens of creativity and design thinking.

For many of us, perhaps, when we think of creatives, we imagine some alternative lifestyle in a post-industrial neighborhood, or perhaps, closer to home, safely managed in small office silos far from where the real decisions are made. This image needs to change as a first step. Organizations and leaders would do far better to bring creatives and people with a creative design mindset in from the cold right into the heart of decision-making, strategy, and business models. Indeed, creative thinking and leadership will likely be at the core of the answer to the challenges we face, as it has always been – both in the ability to think differently around problems and embrace new perspectives and in fostering a culture of innovation. For many leaders and organizations to reap the full benefits of creative thinking as a response to complexity, therefore, our approaches to leadership and doing business need to change.

This partly involves reimagining how we perceive creativity, design, and art – and joining the dots with the business world. That means integrating design and creative thinking, approaches, and processes deeper into our organizations, much in the same way as the most effective sustainable and digital transformations have seen organizations redefine and redraw their business models rather than just tick some compliance boxes or create a new department.

Let’s pause for a moment to think about the artist and artistic process and why there is so much to learn from – and relate to – in the world they inhabit for business leaders aspiring to be more innovative and creative. We might find, contrary to our inner fears, that we have more in common than we thought possible with the artist: that by reframing the role of the artist and the leader, we can recognize and foster our creativity, entrepreneurialism, and powers of innovation – and those of our teams.

On one level, artists are in the business of thinking about what is and what could be. They are curious explorers, painting a new reality from an old reality to provoke reflection and emotions from their audiences, just as an innovator envisions new possibilities to elicit a reaction from an audience of customers and investors. Both take risks – they fail and try again and again.

Artists start from a blank canvas, just as an entrepreneur or executive trying to come up with a new product. Works of art start out as thoughts, ideas, sketches, and experiments; over time, they take form and grow in detail and depth through play and iteration until reaching some form of completion. All we see is a finished work, but the process behind it is often long, arduous, and full of challenges. Is this really any different from the effort and processes behind developing great businesses?

The artist and the business leader must find inspiration from somewhere, from within or without. Where do game-changing ideas come from? Picasso was attributed with the now infamous phrase: “Good artists copy, great artists steal.” Great innovators and leaders are no different. They steal with pride in smart ways. The best innovators see connections between other ideas and innovations already out there to create something new. Executives inside organizations, similarly, must look outside to learn other practices and join the dots to find new solutions.

Artists have a vision, a sense of conviction, and perseverance. Leaders and entrepreneurs, too, need this power of intention and self-belief – a conviction around what they want to achieve, why it is meaningful, and how to stitch together the threads to make it happen.

Artists have a vision, a sense of conviction, and perseverance. Leaders and entrepreneurs, too, need this power of intention and self-belief.

Just as businesses prototype and present new products, artists also engage with their audience and test the waters – they want to understand the response to their works, perhaps to inform their future work. With innovation in all industries, it is vital to understand how customers engage with our products and services and what we can learn from that for the future.

Artists place great importance on the way their work is presented, from the lighting to the storytelling, experience, and ambiance – it’s a kind of theater. Can we say, in business, that we all put as much effort into presenting our ideas, especially internally, as the artist? We have all seen Apple’s carefully curated fanfare for every minor update to its existing product range, but more of us are probably guilty of spending hours on innovating and far less time on thinking about presentation.

On balance, there is more in common between the artists, the innovator, and the leader than first meets the eye – and many lessons we can take from the creative world into the business world. A good place to start is to consider our work environment and how we work.

An artist’s studio is a place of work, but also a space of creativity. How can we rethink our workplaces to make them creative spaces, too? It is easy to fall into the trap of thinking that an environment for creativity means more ping-pong tables and breakfast bars. There is, after all, a balance between what a workplace needs and what creativity requires. What kind of environments – and ways of working – help us produce our best work?

It is unlikely that a video game machine is the answer, but we need to be able to step away from our work to find the mental space for creativity and to take a break if we get stuck on an idea. Creativity needs different kinds of space, including quiet space. When artists run aground on an idea or get frustrated, they often stop and do something else or change their surroundings. Some organizations are good at replicating this through different kinds of space and flexibility around ways of working – what is acceptable and what is not. When we talk about environments, this also means aligning your corporate values and vision with creativity – not just creating the space for creativity but also embodying the spirit of creativity.

If we accept that there is a kind of artist’s code behind creativity, we can decode it, add structure, reduce the chaos, and create a meaningful impact in business. This is one of the foundational thoughts behind design thinking. Design thinking is, in many ways, a version of disciplined artistry at work – a winning combination of art and structure.

How can leaders and organizations leverage this mindset and approach to transform the way they function? Well, there is not one single “way” of design: there are as many ways to design something as there are designers – and that is the point. A designer, simply put, is someone who looks at a need or problem and makes connections between different – perhaps seemingly unrelated – fields and perspectives in productive, intelligent, relevant ways to provide holistic solutions that, at their best, reframe the question and create unexpected value. Design thinking can be applied to any situation and looks above, around, and below the problem to give surprising answers that others struggle to find.

If put at the heart of business, this kind of design thinking has the power to redefine how companies work as well as the products and services they offer. This is why more companies have hired Chief Design Officers (CDOs). CDOs bring design and creative thinking into the heart of decision-making – they can be the catalyst in the room for different views to create a positive impact and make connections that might have been invisible before.

We don’t suggest that everyone in your company needs to become a designer. Instead, a design-led approach would begin with more leaders being open to understanding how designers work and what value they can bring to the table in addressing the big challenges we face. Companies and leaders might claim to be open-minded and future-oriented, but how do they actually put that into practice? Should all companies hire a CDO, not just the furniture makers of this world? Should they all adopt design thinking as a modus operandi for everything they do, from supply chain to communications? There are many inspiring and unusual examples of brands that have embraced design at the heart of what they do and how that has delivered incredible, unforeseen value.

Trusting and working with designers as a leader involves a shift in mindset. It’s about having a brave vision of the future to foster trust between creative thinkers and more traditionally-minded executives – building successively year after year, iteration after iteration, in search of perfection: using design to improve the whole company, not just its products.

If Kodak had listened to Sasson all those years ago, they might have become the next Apple. This is a sobering thought and a cautionary tale for organizations still weighing up how to integrate creativity appropriately into their businesses while others take the leap of faith and race ahead.

Professor of Innovation and Strategy at IMD

Cyril Bouquet is Director of the Innovation in Action program, co-Director of the TransformTECH program and the Business Creativity and Innovation Sprint. As an IMD professor, his research has gained significant recognition in the field. He helps organizations reinvent themselves by letting their top executives explore the future they want to create together.

Director of ECAL/University of Art and Design in Lausanne

Trained as a product designer, Alexis Georgacopoulos took up his current post as Director of ECAL/University of Art and Design in Lausanne in 2011 after running the school’s product design department. Wallpaper* magazine named him among the “100 most influential people in the world of design”.

July 10, 2025 • by Bruno Le Maire in Magazine

Former French finance minister Bruno Le Maire says Europe needs to act urgently to secure its supply of semiconductors or face relegation to the global slow lane. ...

Audio available

Audio available

July 8, 2025 • by Mike Rosenberg in Magazine

A new framework encourages leaders to see the world as PLUTO – polarized, liquid, unilateral, tense, and omnirelational. It’s time to think differently and embrace stakeholder capitalism....

Audio available

Audio available

July 3, 2025 • by Eric Quintane in Magazine

Entrepreneurial talent who work with other teams often run into trouble with their managers. Here are ways to get the most out of your ‘boundary spanners’...

Audio available

Audio available

June 26, 2025 • by Michael Yaziji in Magazine

Forward-thinking leaders proactively shape their external environment, turn uncertainty into certainty, and create substantial value in the process....

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience