At best, this defensive dynamic serves to make us feel better by letting off steam, and we might feel somewhat righteous. But those feelings probably won’t improve performance, and they most certainly won’t leverage the potential of our relationships. The dynamic has created or reinforced boundaries between Mark and Lisa. Instead of closing gaps and building trust and psychological safety, the conversation may have increased the distance between them. This is the risk at the heart of the dance of trust.

Lisa and Mark are high-performing executives. So, why would they self-sabotage and not look for the underlying problems and solutions? The answer is the absence of trust: this discourages them from doing what they need to do – sharing, contributing, questioning, and challenging because self-protection becomes more important.

Letting things out and in

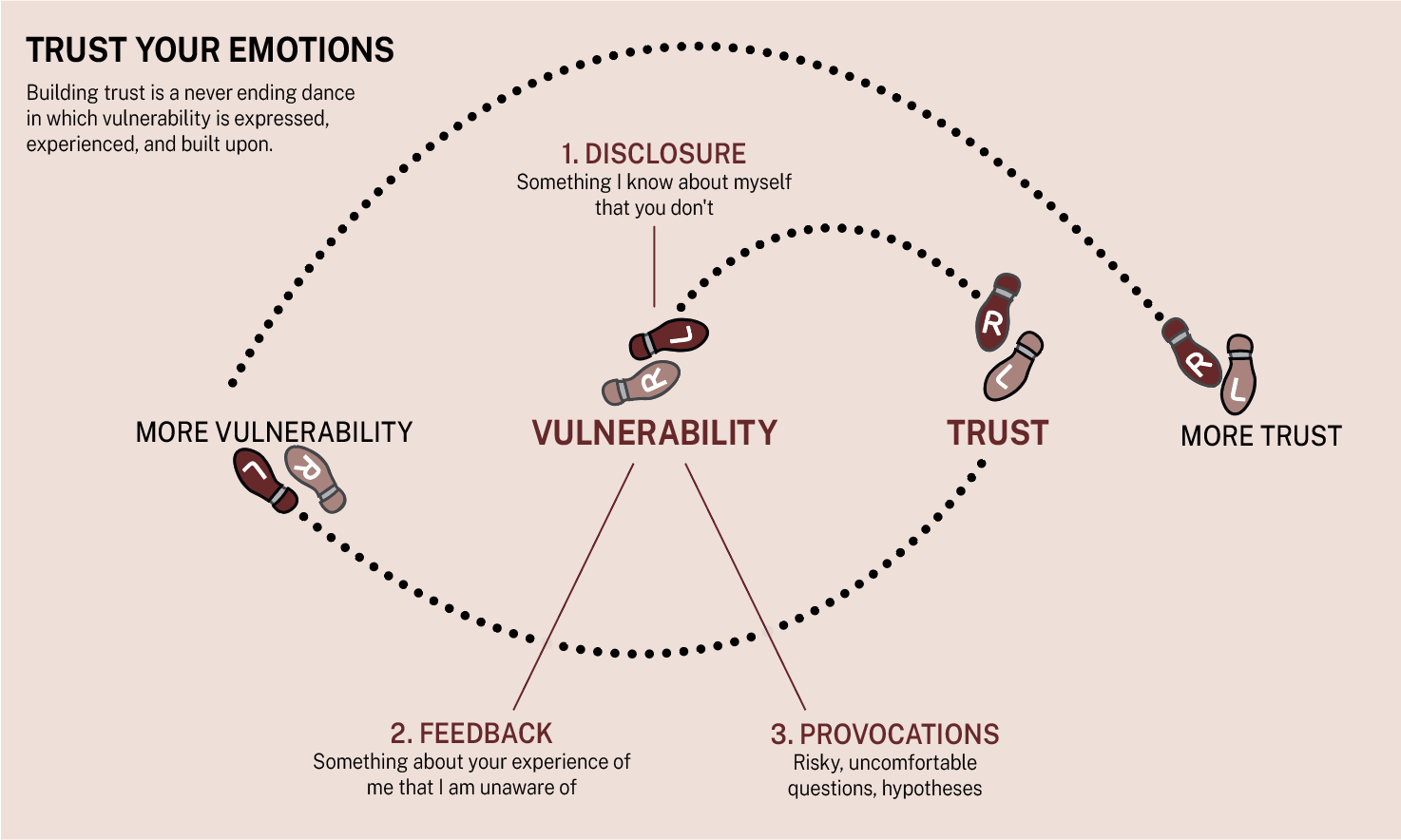

Trust is built on an expression of vulnerability with another person. The word “vulnerability” has been used a lot over the past decade, often referring to the act of self-disclosure. But it is much more than that. Vulnerability means we take a risk of being hurt or wounded. Each time we make ourselves vulnerable, we risk being rejected, mocked, or scorned. We need to be vulnerable and take risks to expose the potential of trust. After this, there is a moment of reaction or reciprocation, where the other person might also be vulnerable.

We can think of vulnerability in three actions:

1. Disclosure – something about yourself that others don’t know.

2. Feedback – something about your experience of others.

3. Provocation – something more impulsive, that will almost certainly invoke defences.

With these three actions, we not only test the nature of the trust we have with others, but we can also grow that trust. Let’s break it down.

1. Disclosure

When we reveal something about ourselves that others don’t know, it requires vulnerability: putting ourselves at risk and waiting for the reaction. This can feel uncomfortable. It’s not by chance that most of us remain pretty buttoned up when we join a new group, team, or organization. It’s only through disclosure and revealing our vulnerabilities that we move beyond seeing each other as roles or figures of greater or lesser authority, representations, or stereotypes. By sharing something honest about ourselves – something about our childhood, for example, or how we truthfully feel in the moment – we invite others to see us as humans with the same hopes and hang-ups as everybody else.

As we disclose, if we are not ignored or mocked, we nudge past our fear of scrutiny, judgment, attack, or rejection toward greater trust in our relationships – and greater faith that those relationships will endure. However, for trust to grow, there is usually a need for a reciprocal disclosure from the other person. Trust isn’t unidirectional, but we can never guarantee what another person might do.

Indeed, there is often that moment between an act of vulnerability and a response, like when you reach out to shake someone’s hand and must wait for them to do the same. That pregnant pause is where the trust is tested. The longer the wait, the more we question the trust. This is the vulnerability we experience in disclosure.

2. Feedback

Honest feedback can be painful to give and receive, and our fear of rejection or reprisal moderates it. Often, we soften or edit feedback because we don’t want to hurt someone’s feelings, provoke anger, or risk their disappointment. How many times have you watered down your assessment of a colleague’s performance? How often have you told a white lie to spare them pain? “Thanks, Lisa, good job” instead of “Lisa, this was OK, but it feels a little incomplete in these places.” Or instead of “Mark, I understand your concerns,” how about “Mark, I understand your concerns. However, your tone is making me nervous and uncomfortable.”

Few of us enjoy giving or receiving critical feedback, but reciprocal feedback in real time is a lynchpin of building trust.

3. Provocation

If feedback is painful, provocation can be downright grueling, requiring reserves of vulnerability and courage. This is where trust-building can so easily go wrong. As we have just seen, asking hard or challenging questions doesn’t come easily to most of us and can trigger all kinds of defensive mechanisms and behaviors. Provocation entails entering other people’s personal space and boundaries. They may be unwilling to disclose because they feel invaded or attacked, and their initial reactions might be highly defensive.

Yet, if we want to leverage the potential of our relationships, we must continuously test, interrogate, and challenge each other. Moving forward means constantly questioning assumptions and beliefs. Of course, there is a difference between provoking for the sake of it, needling a colleague or a power play, and asking hard questions to advance the collaboration toward shared goals and purpose. This may require time to allow people to digest the provocation. This is what Lisa and Mark failed to do, as Lisa handed in her resignation.

Audio available

Audio available

Audio available