The AI productivity illusion

Confusing efficiency with productivity is to mistake speed for direction, and execution for value. Hamilton Mann explains how to avoid the pitfalls in your AI transformation...

Audio available

Published November 24, 2025 in Artificial Intelligence • 5 min read

Not unexpectedly, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang is an AI super fan. “I use it (AI) every day, and it’s improved my learning, my thinking,” he said during a recent visit to the UK. “It’s helped me access information and knowledge a lot more efficiently. It helps me write, helps me think, it helps me formulate ideas.”

He’s not alone. An IBM study released in May 2025 found that 61% of CEOs are adopting AI agents.

Amar Bhidé, Professor of Health Policy and Management at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, is skeptical. “CEOs fib about their use of AI because they want to be perceived as forward-thinking or are trying to sell AI products,” he says. “Anyone who has tried to use LLMs to do anything useful would stop fairly quickly. If I knew of a CEO who was using AI in a meaningful way, I’d be tempted to short their stock.”

Bhidé is no technophobe. He obtained his first degree in chemical engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai, purchased his first PC in 1980, and coded his personal website. “I try every new technology,” he says. “I’m a sucker for it.”

But a series of underwhelming personal and professional experiences undermined Bhidé’s faith in artificial intelligence. For example, one of his students submitted an AI-assisted assignment that falsely claimed that Russian-American Nobel Prize-winning economist Simon Kuznets had helped make the discovery that ulcers could be treated with antibiotics. More generally, he found that AI-generated summaries of his academic papers completely missed the main point of the thesis. He’s well aware that large language model (LLM)-generated code can be riddled with bugs or simply fail to work.

“I see two issues with LLMs,” he says. “One is that many of them are rubbish. But even the ones that work well are not cost-effective. The current AI mania means investors and CEOs are subsidizing investments in AI.”

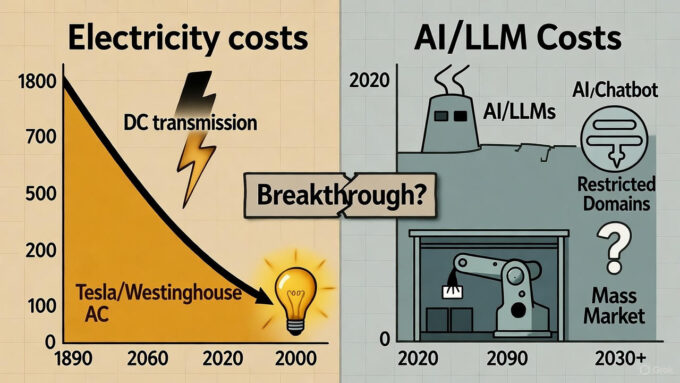

Bhidé disagrees with predictions that the cost of LLMs will plunge as the technology matures. Such a reduction would require a breakthrough, for example, Tesla’s discoveries around alternating current, which drastically reduced the cost of electricity transmission. Many assume that AI will inevitably experience something similar. The case of nuclear fusion shows that it is not a given. If there is no dramatic cost breakthrough, many promising AI use cases will be unviable because they cannot be marketed at an affordable price.

Bhidé believes that, ultimately, the cost and adoption trajectory of AI could be similar to that of robots. “We’ve been told for decades that robots will take over everything,” he says. “They didn’t. There are valuable use cases like managing warehouses. Like this, there could be useful applications for LLMs without dramatic cost breakthroughs, in restricted domains.”

LLMs seem to have been designed to flatter the user, thereby encouraging their continued use.

Meanwhile, psychological manipulation can get users dangerously hooked. “LLMs are programmed to project authority while preying on the insecurities of users,” says Bhidé. “Their responses are at once utterly confident and aim to affirm users’ opinions or desires.”

If a CEO asked an LLM a series of questions about business strategy, the replies would more than likely align with the CEO’s existing views, assuring them that their thinking is sound and that they are on the right course.

“They play courtier, not devil’s advocate,” continues Bhidé. “LLMs seem to have been designed to flatter the user, thereby encouraging their continued use. ’Oh, what a brilliant idea!’ they will effectively say, convincing the user that they are really smart.”

“Continuously changing circumstances, from regulation and geopolitics to technological advancements and customer preferences, require executives to make decisions in a state of uncertainty.”

To grasp the genuine potential of both LLMs and a broader set of AI technologies, we must understand the difference between statistical risk and contextual uncertainty. This distinction is central to Bhidé’s most recent book, Uncertainty and Enterprise: Venturing Beyond the Known. In the book, he points to the self-evident truth that statistical risk is quantifiable. Based on the assumption that the future will be similar to the past, risk can then be assessed using numerical, probabilistic measures.

A player sitting at the roulette wheel plays a game of risk, deciding how much money to bet on a certain probability of winning. A doctor explaining the life expectancy of a newly diagnosed lung cancer patient turns to data about similar cancer patients.

Uncertainty arises in events that are to a meaningful degree without precedent. It cannot, therefore, be accurately measured because past events no longer inform future possibilities.

“Risk is predicated on stationary phenomena, like a game of chess with fixed rules or the motion of planets, where what is going to happen tomorrow is exactly or very like what happened in the past,” says Bhidé. “In these cases, AI could, if programmed correctly, help determine the most likely outcome and the best choice to make. But outside of chess and the natural world, we invariably face uncertainty. In human affairs, we should expect the future to diverge from the past and therefore be skeptical about statistical extrapolation.”

This is especially true in business. Continuously changing circumstances, from regulation and geopolitics to technological advancements and customer preferences, require executives to make decisions in a state of uncertainty, rather than based on defined risk. They have to imagine what will happen – and imaginatively persuade others that their imagined future is desirable and attainable.

Faced with uncertainty, neither old-fashioned statistics nor oracular LLM offer much assistance. For executives, the challenge is to distinguish between what AI can reliably compute and what the human imagination can create.

Professor of Health Policy at Columbia University Medical Center

Amar Bhidé is Professor of Health Policy at Columbia University Medical Center (Mailman School of Public Health) and Professor of Business Emeritus at Tufts University (Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy). He has researched and taught about innovation, entrepreneurship, and finance since 1985.

A member of the Council on Foreign Relations, and a founding editor of Capitalism and Society, Bhidé is the author of Uncertainty and Enterprise: Venturing Beyond the Known (Oxford 2025).

Bhidé earned a DBA and MBA from Harvard Business School and a B. Tech from the Indian Institute of Technology (Bombay).

January 26, 2026 • by Hamilton Mann in Artificial Intelligence

Confusing efficiency with productivity is to mistake speed for direction, and execution for value. Hamilton Mann explains how to avoid the pitfalls in your AI transformation...

Audio available

Audio available

January 23, 2026 • by Michael R. Wade, Konstantinos Trantopoulos in Artificial Intelligence

To create the best customer experience, CXOs should leverage AI to build dynamic systems that adapt in real time to customer needs. We explore how leading companies are using this approach today....

January 20, 2026 • by Faisal Hoque, Paul Scade , Pranay Sanklecha in Artificial Intelligence

For multinationals, especially in strategically sensitive sectors such as energy, finance, and technology, traditional defense policies offer inspiration as they develop robust AI strategies. ...

January 8, 2026 • by Mark Seall in Artificial Intelligence

To truly transform, organizations must overcome strategic and conceptual pitfalls. Here is why so many leaders continue to get it wrong. ...

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience