How to harness the power of nonmarket strategy

Forward-thinking leaders proactively shape their external environment, turn uncertainty into certainty, and create substantial value in the process....

Audio available

by David Bach, Richard Baldwin, Simon J. Evenett Published January 20, 2025 in Strategy • 9 min read

Donald Trump brings a distinct mode of governance to the US Presidency. Central to his leadership style is unpredictability – including bold promises and threats that grab the headlines, thrill his base, and destabilize others. Deporting millions, dismantling wind farms, indicting Democrats, buying Greenland, and banning vaccines are just some of the pledges Trump or his allies have made. These pronouncements appear almost daily, creating what can best be described as a “policy fog.” The ability to see through it will be critical for global business leaders in the weeks and months ahead.

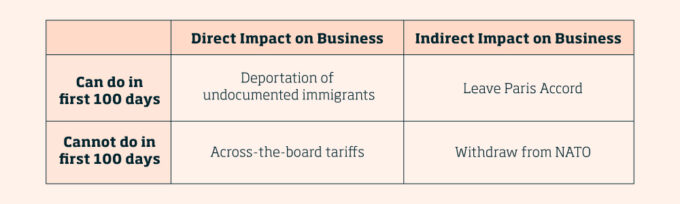

Classic enterprise risk management tools won’t be enough. Executives would do well to separate policies along two dimensions. The first dimension distinguishes actions that the new president can execute in the near term and those that – for legal or constitutional reasons – take time or require the cooperation of other independent actors, such as Congress.

The second dimension distinguishes actions that would have a direct impact on business and those that would affect business more indirectly. This analysis naturally suggests a 2×2 matrix for piercing the policy fog – the Clarity Compass. Let’s bring this alive with four hot topics.

If President Trump’s first term was anything to go by, shock and awe can be expected.

Steps to restrict migration are in the power of a US president. Joe Biden used executive orders to reverse many of Donald Trump’s prior policies. Given what he said during the election campaign and since – and echoed by his so-called “border tzar” and other senior White House appointments – tough restrictive measures are on the cards in the first days of a second Trump term.

If President Trump’s first term was anything to go by, shock and awe can be expected. The recall he introduced via an Executive Order on 27 January 2017 – labeled the “Muslim travel ban” – prevented entry to the US for nationals from seven countries for 90 days. Two further bans were promulgated that year, partly in response to successful legal challenges. This example serves to make two points relevant today: US presidents can make high-profile changes in immigration policy overnight but those changes can be challenged, delayed, and even overturned.

Fast forward to 2025, it is President Trump’s pledge to deport millions of undocumented immigrants that will generate waves. Two questions immediately arise: Can he do it? And would it impact business?

The answer to the second question is almost certainly yes. The number of undocumented immigrants in the US is estimated to be 11 million – though some believe it is even higher. Crucially, these citizens don’t live in hiding – they hold jobs, pay taxes, and often have children or spouses who are US citizens. Roughly 400,000 undocumented students attend US colleges. The economic costs of mass arrests would be severe, and worker shortages – from hospitality to domestic services, transportation to manufacturing – would immediately ensue. Moreover, millions of legal immigrants might stay at home for fear of getting swept up in mass arrests. This would not only affect US-based employers but also dent domestic consumption, thus hurting some foreign firms as well.

But would Trump do it given the costs? Again, the answer is almost certainly yes. Deportation pledges have been the 2024 equivalent of ‘Build the wall!’ in the 2016 campaign and several Republican-led states, such as Texas, have already prepared for mass detentions. Indeed, the US federal government does not have the infrastructure and personnel to round up millions of migrants, legal or illegal. It is also true that such a dramatic step would require the collaboration of local police forces, and many states have made it clear they don’t support mass deportations. However, snatching several thousand migrants off the street, out of schools, and from their workplaces, documented by both sides with gut-wrenching social media footage, could prove enough to wreak economic havoc. Critically, it’s not only the actual policy actions that matter, or the scale of those actions. Business impact may instead be driven by how stakeholders react.

There is precedent for an American president proclaiming across-the-board tariff increases, but that was over 50 years ago.

Sourcing from abroad is another bugbear of America’s incoming president. In recent months Trump threatened to impose 60% tariffs on goods from China, 25% on goods from Canada and Mexico, and 10-20% import taxes on products from everywhere else. How should executives assess these threats?

There is precedent for an American president proclaiming across-the-board tariff increases, but that was over 50 years ago. President Nixon took this drastic step in 1971, increasing tariffs by 10% for six months under a law that has since been scrapped. Whether President Trump has the legal authority to impose tariff increases across the board is debated by legal experts (most think it unlikely, but still.)

Formally, trade policy is a Congressional prerogative under the US Constitution – presidents can only take steps under authority granted by Congress. Here, differentiating between what a president can do from what they cannot do matters. Trump was only able to hike tariffs on imports from China during his first term after conducting lengthy investigations. He is very unlikely to lay similar groundwork for across-the-board tariff increases in the first 100 days.

However, because those investigations against China were conducted and concluded in the past, a US president can take further measures against imports from that country. That is exactly what President Biden did last year in May. A newly installed President Trump could hike import tariffs on China on Day One – or set a date to do so. These considerations mean targeted tariffs against China are much more likely than across-the-board tariffs.

Anticipating these targeted tariffs, many businesses have sought to lower their commercial exposure by sourcing more from China in the second half of last year, contributing to a record Chinese trade surplus.

Executives are well placed to trace through the direct effects of higher import duties on goods sourced from China. They should know whether they can induce their Chinese suppliers to effectively pay some – or all – of the duty increase, how much their overall cost base will rise, and how much of the latter can be realistically passed on to customers. No doubt many executives have dusted off their playbooks from the US-China Trade War in President Trump’s first term.

But this is not enough. There are also second-order effects. Shut out of US markets, Chinese exporters will seek opportunities elsewhere. So-called ‘trade deflection’ could thus affect business everywhere even if Trump tariffs remained targeted. Moreover, US tariffs, particularly when combined with tax cuts, could fuel US inflation, and increase the value of the dollar as interest rates remain high. Expect volatility in currency – and bond markets, even without across-the-board tariffs.

Under President Obama, the US signed the Paris Accord on Climate Change only for President Trump to withdraw – a decision that, for procedural reasons, only took effect the day after Joe Biden denied Trump a second term and that Biden, once in office, swiftly reversed. Now Trump returns to the Oval Office determined to withdraw again. Experts agree that he can do so by executive order, just as he did the first time. The withdrawal would become effective one year later.

Danish wind farm operator Orsted lost 14% of its value the day after Trump won reelection and another 7% last week when the President-elect renewed his pledge to stop all new wind projects. However, even though a Paris withdrawal by the world’s largest economy in the year that the 1.5C threshold was first breached would be a slap in the face of global climate efforts, the impact on business – US and global alike – would likely be minor. The Biden Administration invested over $300bn in green tech over the past two years, much of it in Republican-controlled ‘red’ states. That money isn’t coming back and it has irrevocably changed the US energy landscape. Orsted is particularly vulnerable because of the big bet it has placed on offshore wind, and here the US federal government plays a key role. Other green tech companies have fared far better. Paris or no Paris, Tesla’s stock is up 75% since Trump’s victory.

Withdrawing from NATO is far more complicated because the Senate ratified the treaty with a vote of 82 to 13 back in 1949.

If President Trump can withdraw from Paris with the stroke of a pen, can he do the same with NATO? The answer is no, at least not without cooperation from Congress or the courts. Foreign treaties require ratification by the US Senate with a two-thirds majority. Knowing that Obama would never secure such a vote for Paris, the agreement was written such that the US president could commit the country via executive order. That makes the Paris Accord vulnerable.

Withdrawing from NATO is far more complicated because the Senate ratified the treaty with a vote of 82 to 13 back in 1949. Trump could attempt to withdraw unilaterally, but the legal challenges that would almost certainly follow could take years. The US Supreme Court has never definitely ruled on unilateral treaty withdrawal.

While a formal NATO withdrawal is thus highly unlikely during the new administration’s first 100 days, there is no question that the effort alone could undermine Article 5, which enshrines the alliance’s commitment to collective defense. That alone could have a dramatic impact on global business as Europe, Canada, Japan, South Korea, and other traditional US allies would need to ramp up defense spending quickly, crowding out private investment and shaking confidence in key markets.

At its core is a recognition that, no matter the strongman tactics, the US Constitution was designed to limit independent action from each arm of government.

No doubt some corporate executives eagerly await the deregulation they expect from the new US Administration. Whatever benefits arise must be seen alongside the calculated creation of policy uncertainty that is President Trump’s leitmotif. The resulting policy fog will put a premium on being able to parse the associated governance chaos.

For sure, we could conclude with the standard recommendations about tracking policy moves, scenario planning, stakeholder management, etc. But that doesn’t get to the heart of the matter: the brain scaffold that we reckon corporate executives need to peer through four years of policy fog.

At its core is a recognition that, no matter the strongman tactics, the US Constitution was designed to limit independent action from each arm of government. No matter how much he may chafe over these limitations, President Trump is bound by certain rules and must accept court judgments he may not like (such as the recent Supreme Court decision on the TikTok ban.) Differentiating between what the new President directly controls in the near term and what he cannot is vital.

The timetable cannot be defied either. The 2017 tax cuts expire this year. The Congressional elections of 2026 are baked into the calendar and will have important implications for getting controversial reforms enacted. That governance processes take time, and can be challenged and slowed down, gives executives time to prepare considered responses. Remember the cautionary advice: marry in haste, repent at leisure.

A third aspect is the recognition that even seemingly non-business policy decisions can have indirect consequences for corporate performance, as we’ve argued earlier. It is not just a matter of how your firm navigates Trump’s political fog – if, how, and when others react, including foreign governments, matters too.

President of IMD and Nestlé Professor of Strategy and Political Economy

David Bach is President of IMD and Nestlé Professor of Strategy and Political Economy. He assumed the Presidency of IMD on 1 September 2024. He is working to broaden and deepen IMD’s global impact through learning innovation, excellence in degree- and executive programs, and applied thought leadership. Recognized globally as an innovator in management education, Bach previously served as IMD’s Dean of Innovation and Programs.

Professor of International Economics at IMD

Richard Baldwin is Professor of International Economics at IMD and Editor-in-Chief of VoxEU.org since he founded it in June 2007. He was President/Director of CEPR (2014-2018), a visiting professor at many universities, including MIT, Oxford, and EPFL, and a long-time professor of international economics at the Graduate Institute in Geneva. Richard is an expert in global economic policy and theory, specializing in international trade.

Professor of Geopolitics and Strategy at IMD

Simon J. Evenett is Professor of Geopolitics and Strategy at IMD and a leading expert on trade, investment, and global business dynamics. With nearly 30 years of experience, he has advised executives and guided students in navigating significant shifts in the global economy. In 2023, he was appointed Co-Chair of the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on Trade and Investment.

Evenett founded the St Gallen Endowment for Prosperity Through Trade, which oversees key initiatives like the Global Trade Alert and Digital Policy Alert. His research focuses on trade policy, geopolitical rivalry, and industrial policy, with over 250 publications. He has held academic positions at the University of St. Gallen, Oxford University, and Johns Hopkins University.

June 26, 2025 • by Michael Yaziji in Strategy

Forward-thinking leaders proactively shape their external environment, turn uncertainty into certainty, and create substantial value in the process....

Audio available

Audio available

June 4, 2025 • by Stéphane J. G. Girod, David Branch in Strategy

The traditional e-commerce model is on its last legs. In a disrupted luxury landscape, brand leaders are shifting focus to unified commerce, hyper-personalization, and deeper digital storytelling to completely reinvent the customer...

June 3, 2025 • by Anna Cajot in Strategy

Donald Trump’s tariff tactics offer a bold case study in game theory in negotiations. By setting the rules early, limiting options, and projecting power through credible threats, his approach shows how negotiations...

May 27, 2025 • by Robert Earle, Karl Schmedders in Strategy

With solar power flooding grids, the duck curve creates both challenges and opportunities for businesses. Learn how smart companies can harness this shift to cut costs and boost efficiency....

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience