The end of corporate passivity: Why business leaders must shape geopolitics, not just react to it

To thrive in a fragmented world, business leaders must stop being passive spectators and start actively shaping geopolitics, urges IMD’s Arturo Bris...

by Frederic Barge, Karl Schmedders Published April 27, 2023 in Governance • 6 min read

As executive compensation soars back to pre-COVID-19 levels, and the gulf in pay between chief executives and employees expands, business leaders are under increasing pressure to design financial incentives in ways that reflect companies’ broader societal responsibilities while also creating long-term value for investors and other stakeholders.

All too often, compensation plans have tended to encourage executives to pursue short-term profit maximization, often at the expense of environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations. That is now changing: the proportion of S&P 500 companies embedding ESG goals into their executive bonus plans rose from 57% in 2021 to 70% last year, according to consultants SemlerBrossy.

The challenge for such businesses is the need to balance sustainability with profitability. Cutting greenhouse gas emissions, for example, is likely to inflate costs and lower growth in the short term, even if that’s dwarfed by the price of inaction.

Companies have a fiduciary duty to their shareholders and other stakeholders. How many bad quarters can a CEO have before investors and the board call for their head? The tragic case of Danone’s former boss Emmanuel Faber underlines the pitfalls. Faber changed the company’s legal status to enshrine its social purpose, declaring he had “toppled the statue” of Milton Friedman, the late free-market economist. Nine months later, Faber was ousted after Danone’s investors hit out at the company’s weak share performance compared with its rivals.

Top executives may wish to avoid a similar fate and keeping investors happy often prevents them from making the investments necessary to tackle longer-term societal problems. They’re being pulled in multiple directions, however. Many businesses also face pressure from other stakeholders (customers, employees, regulators) to look beyond profit.

Executive pay powerfully shapes how executives behave, so a more balanced mix of targets, incentives and accountability structures would help companies achieve better outcomes for both investors and society. Reward Value, a non-profit, has developed three principles for responsible remuneration, presented at the World Economic Forum earlier this year.

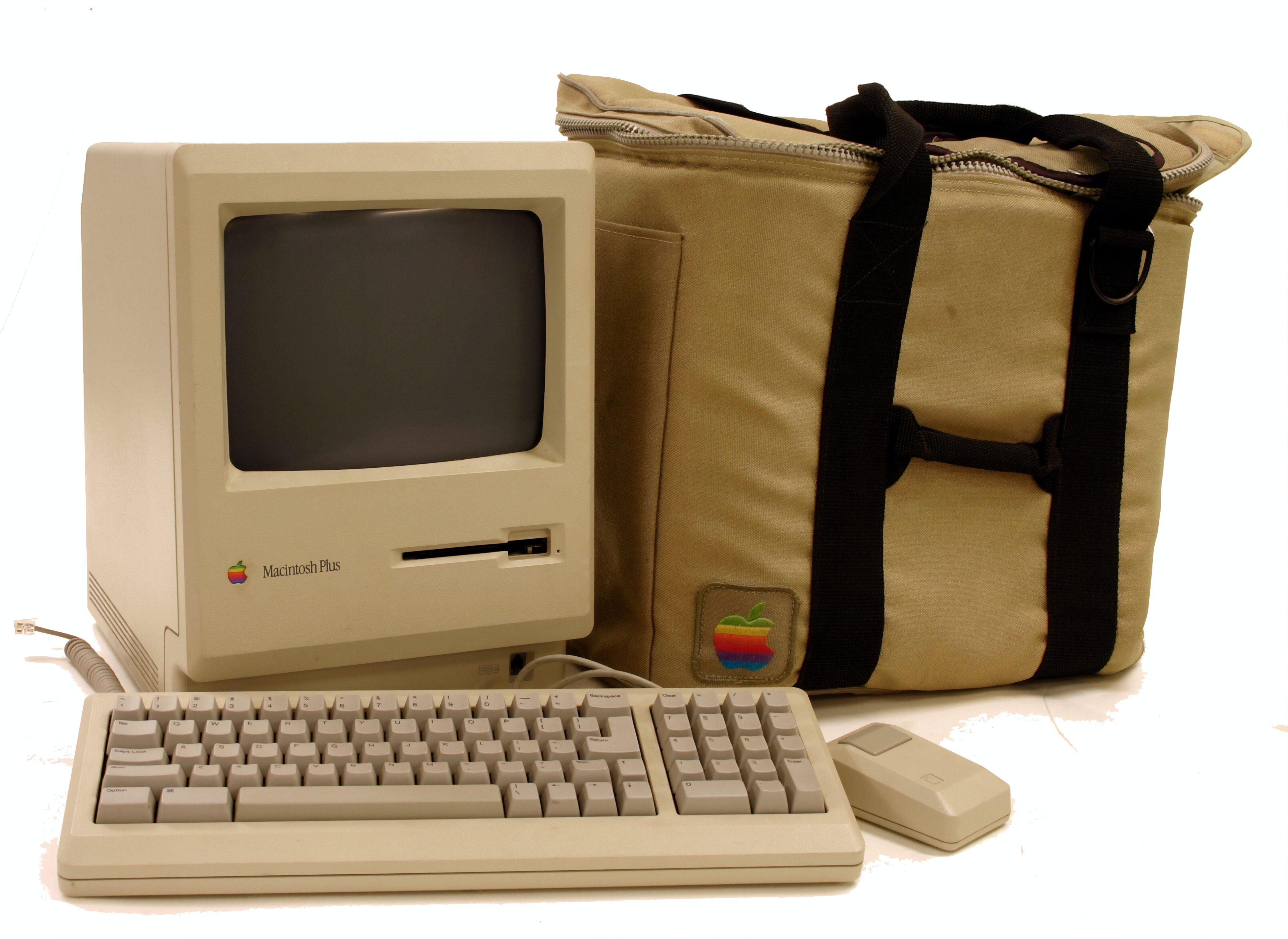

“If you bought $10,000 worth of Apple shares in 1984 when it launched its first Mac computer, you would be $3.8 million richer today. Therefore, Apple’s LIVA over this period is $3.8 million”

Financial performance measures play a key role in determining executive pay. We think companies should broaden those performance targets to include the long-term value generated for all stakeholders, not just short-term operational goals.

On the financial performance side, one yardstick is the Long-Term Investor Value Appropriation(LIVA) framework, which uses share price data to calculate long-term value creation, or destruction, for shareholders.

LIVA reflects actual cash returns over time from share price appreciation, share buybacks and dividend payouts from holding shares in a company, minus the opportunity cost of investing in that company. For example, if you bought $10,000 worth of Apple shares in 1984 when it launched its first Mac computer, you would be $3.8 million richer today. Therefore, Apple’s LIVA over this period is $3.8 million.

While it’s possible to measure non-financial performance, the lack of reliable data makes it harder. One option is to use the Impact Weighted Accounts (IWA) framework, which puts a monetary value on a company’s societal impact, such as its carbon emissions. This allows for a more direct comparison between financial and non-financial performance. Taken together, the IWA and LIVA frameworks can be used to gauge long-term stakeholder value creation.

When it comes to embedding such performance data into executive pay plans, it can help to set KPIs that are specific to the organization – such as the environmental footprint of an airline, or worker health-and-safety for a mining company. This ensures the C-suite has a financial incentive to protect its stakeholders.

But it’s important that the compensation model includes both fixed annual pay and a longer-term incentive. Most compensation packages come with “absolute goals”, meaning the executives need to hit a specific number to get their bonus. But these targets usually have a one-year horizon. Even when bonuses are paid based on relative performance, say compared to peer companies, the average time horizon is just three years.

All too often, the prevalence of short-term bonus plans leads to manipulation by executives who try to “game” their remuneration, often to the detriment of shareholders. For example, executives may delay certain payments or investments in research and development (R&D) to keep cash flow targets alive until after they get their bonus.

“Executive pay has soared in the past year, partly thanks to bonuses for lower targets set during the pandemic. But that can seem at odds with the idea that companies should be creating a fairer and more just society”

Moreover, short-term targets may conflict with long-term goals to tackle urgent societal challenges such as the climate crisis —an issue that Mark Carney, the former governor of the Bank of England, calls a “tragedy of the horizon”. This means the effects of global warming lie beyond the time horizons of most leaders.

One way to counter short-termism is to extend the vesting period for bonuses to even beyond the tenure of the executive. Post-crisis regulation made this practice common for senior bankers, but not in other sectors. Changing that would liberate executives from focusing on annual performance targets and reward them based on value creation that lasts.

When it comes to rolling out these new targets, you’ll need strong corporate governance.One thing to consider is the extent to which wider stakeholders should be involved. A broader representation on remuneration committees would help ensure that ESG issues are not only incorporated into pay plans, but that these new structures are upheld – and, if necessary, defended.That may also stop executives from attempting to use their influence within the company to get their preferred candidates on remuneration committees.

Another potentially contentious issue to consider is whether it is necessary to include a “clawback” provision, which can be used to recover pay or stop future payments in the event of a major social or environmental problem. At a time when greenwashing is rife, we believe that such a provision is important.

Finally, while climate concerns are front and center of ESG considerations, companies should also be thinking about how executive pay can be used to further progress on equality goals.

Executive pay has soared in the past year, partly thanks to bonuses for lower targets set during the pandemic. But that can seem at odds with the idea that companies should be creating a fairer and more just society. One thing to keep in mind is the pay ratio between bosses and workers. Research from Deloitte found the ratio has been increasing in the FTSE 100, reaching 1:81 last year compared with 1:59 in 2020.Companies that want to align compensation with equality will need to ensure the gap doesn’t widen further.

Founder of Reward Value

Frederic Barge is the founder and managing director of Reward Value, a non-profit foundation focused on modernizing executive remuneration in support of sustainable long-term value creation. He is a former KPMG partner and HR executive at large organizations. Frederic is a published author and recognized thought leader with particular expertise in executive remuneration, private equity compensation programs, equity plans, corporate governance, HR aspects in M&A transactions, and performance assessment.

Professor of Finance at IMD

Karl Schmedders is a Professor of Finance, with research and teaching centered on sustainability and the economics of climate change. He is Director of IMD’s online certification course for structured investment and also teaches in the Executive MBA programs and serves as an advisor for International Consulting Projects within the MBA program. Passionate about sustainable finance, Schmedders believes that more attention needs to be paid to on the social (S) and governance (G) aspects of ESG to ensure a fair transition and tackle inequality.

June 23, 2025 • by Arturo Bris in Governance

To thrive in a fragmented world, business leaders must stop being passive spectators and start actively shaping geopolitics, urges IMD’s Arturo Bris...

May 19, 2025 • by Peter Voser in Governance

Board members have a central role to play in helping organizations steer a safe path in a polarized and skeptical world....

Audio available

Audio available

April 28, 2025 • by Jordi Gual in Governance

Companies pursuing ESG goals increasingly face a backlash from shareholders who fear a drop in financial performance. Changes to corporate governance may be needed to restore trust on both sides of the...

Audio available

Audio available

March 27, 2025 • by Jennifer Jordan, Alexander Fleischmann in Governance

Take our quiz to see if you're well-placed to implement new European rules on boardroom equality....

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience