Silicon Valley executives often claim that they want to ‘make the world a better place’ by solving the biggest challenges of our time. In pursuit of this goal, they invest millions in research and development (R&D). “Astro” Teller, the entrepreneur and scientist who ran Google X – “The Moonshot Factory” – once famously compared his innovation lab to “Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory, [where] the goal is to have an impact on the world and then worry later about making money on it.” But how can the true value creator track record of a firm be established?

Judging the underlying ability of firms to create value with accounting profit measures, such as EBIT, can be misleading. The latter ignores the opportunity costs of capital and penalizes firms that choose to make R&D outlays. Instead, we drew inspiration from Economic Value Added measures. Our economic profit measure adjusts a firm’s EBIT by (1) adding back voluntary firm expenditures such as R&D and advertising outlays, (2) deducting taxes paid, and (3) subtracting the weighted average cost of capital times the total capital invested in the business (minus excess cash.)

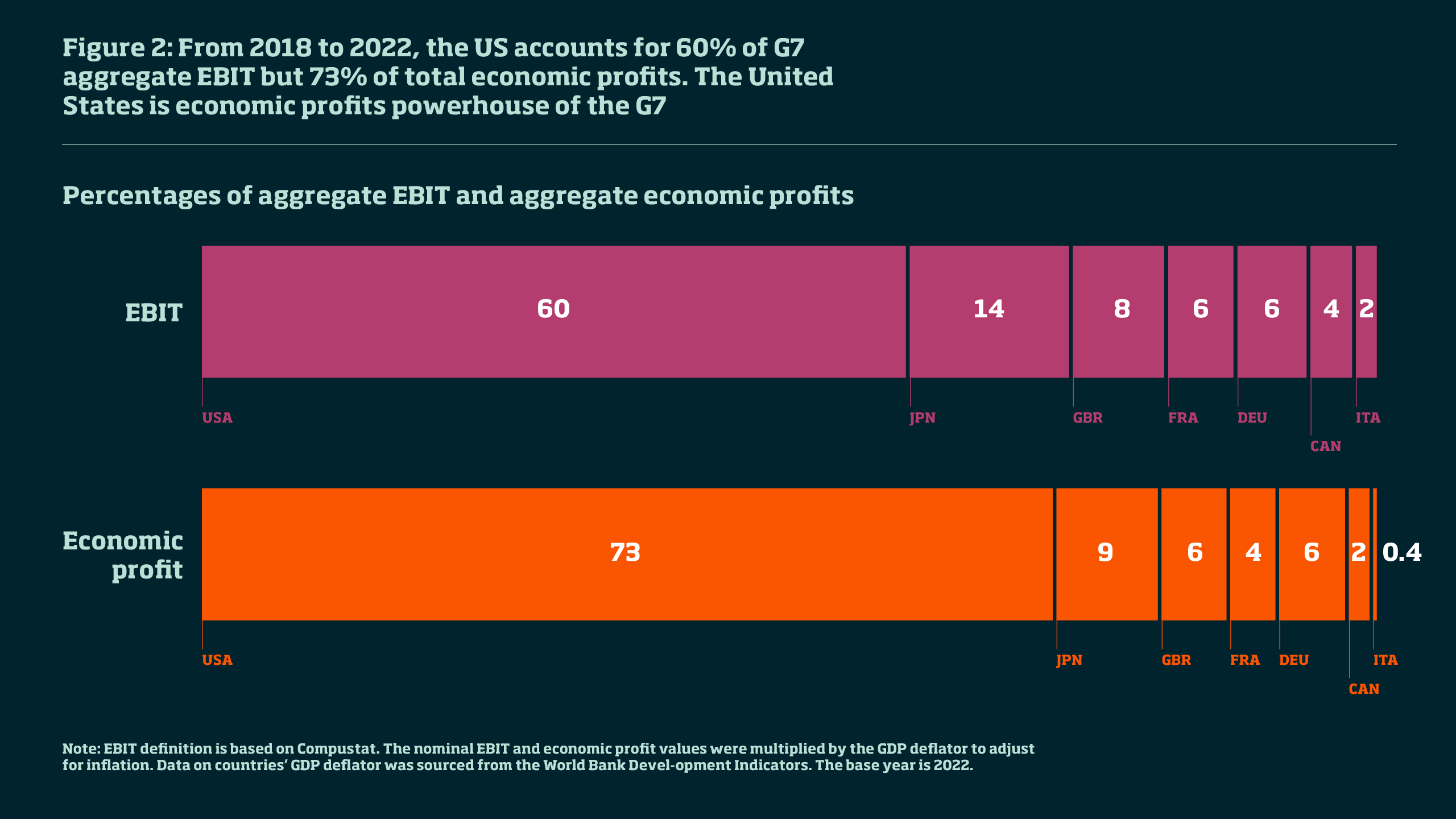

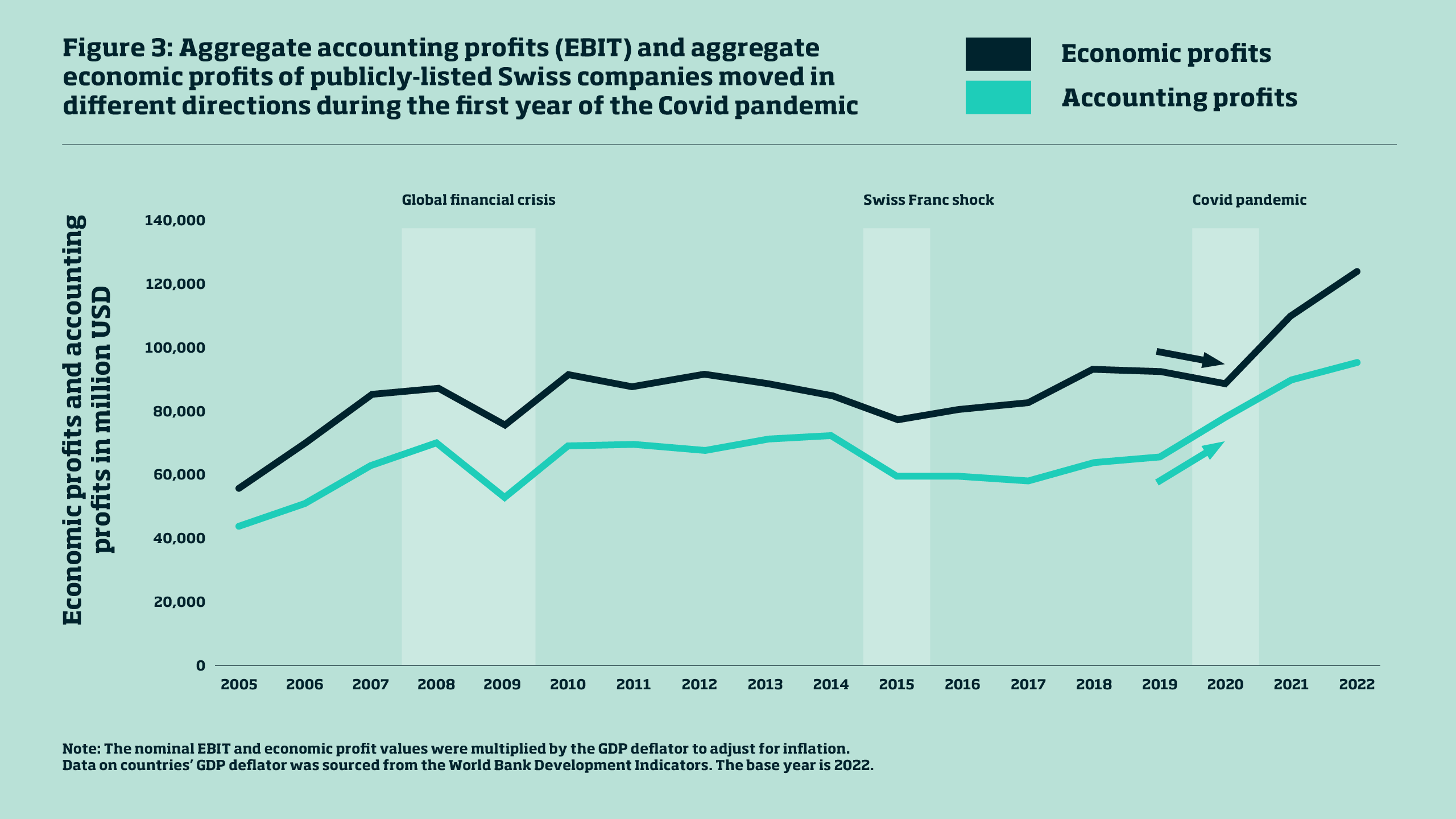

Economic profit measures do not seek to replace other informative financial metrics (such as Free Cash Flows) or macroeconomic metrics (like GNP). However, our initiative contains economic profit estimates on nearly 40,000 publicly listed firms from the world’s largest economies, plus some medium-sized economies such as Switzerland and South Africa, since 2005. We have found at least three ways in which accounting profit measures can be misleading.

An inaccurate gauge of the value created by firms

First, accounting profit metrics result in misleading cross-firm comparisons of value creation from current operations. Take Johnson & Johnson and Walmart. Figure 1 shows their reported EBIT figures were similar in 2022. Yet, Johnson & Johnson’s economic profit was almost three times higher, largely due to its immense R&D spending of $15bn, which Walmart did not match. The healthcare giant’s R&D focus certainly played no small part in the development of one of the world’s COVID-19 vaccines. While it would be going too far to argue that the success of a nation’s largest companies expressed by our economic profit measure is the sole driver of national economic performance and innovation, it is difficult to envisage long-term aggregate improvements in living standards without such flagship companies flourishing. Economic profits do a much better job of capturing actual value creation.