How multiple role identities are managed

For most family directors, stepping back into a passive role is not a viable option, so the second phase of our research focused on how multiple role identity struggles are managed by the board of family firms.

When multiple role identity struggles are not managed correctly, they can affect entrepreneurial orientation and performance, and so their management is vital. Existing research suggests that this is usually managed in one of two ways: internal, by an individual, and external, through their environment.

There is a growing understanding that individuals hierarchically organize their multiple role identities, with the more salient identities placed higher in the hierarchy. However, in a family firm, when the roles of patriarch and business director are of equal importance and both pressingly relevant to a board discussion, how does an individual manage the conflation?

This was the case for one of the family firms that we spoke to during our research that had recently faced a difficult strategic and interpersonal situation. This is an extract from our interview with an advisor of a large family firm.

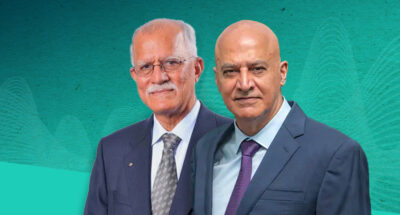

“The company is owned equally by the chair and his brother. The brothers resigned from their executive roles as CEO and CFO respectively when the company was thrown into a very difficult period due to an event in their industry. They wisely hired a non-family CEO who has been doing an excellent job helping the company recover. The complication for the board chair (now 63) is that he has sons working in the family company who are also performing well, and the chair had wanted one or more of them to lead the company. If the company gives the non-family CEO a long-term employment contract (desired by the CEO and supported by the independents on the board) the chairman’s sons would need to wait years to lead the company. The chair’s brother maintained a neutral position. The other board members felt that the non-family CEO was needed for some time to reorganize the company and transform the company’s portfolio.

During my meetings with the family chairman, I appreciated that he was deeply torn about what to do. As a father he wanted to select one of his sons for future leadership; as a board chairman and owner, he knew he should consider what was in the best interest of the company and the owners, which on balance favored keeping the non-family CEO.

The board members performed a careful analysis of the qualifications of the CEO and sons of the chairman for the job of CEO. They also spent considerable time discussing the issue with the board chair, getting him to understand how his role as a father was confusing his obligations as a board chair and owner of the company. The independent board members then helped the board chair fashion useful and attractive roles for two of his sons in a new venture by the company that kept the CEO in place. In this case, the director who knew the chair best kept the other directors informed and they worked as a team to help the father-chair come to a decision. The board members got to know the sons of the chair and tried to demonstrate to them that they were supportive and respectful of the family and wanted to help the company make a decision that was in the interests of the owners. This was a team effort.”

Our research found an unexpected focus on external management and how environmental factors in a family firm can help its individuals manage their multiple role identities. Something we coined Boardroom Structural Forces. It refers to the view that a family boardroom, in its physicality, and along with fellow board members, can help a director separate their role identities.