At a recent Discovery Event, about 80 executives explored the ins and outs of negotiations. They took part in a number of exercises, and through an analysis of the behavior and the process to reach a deal, they uncovered hidden assumptions that people typically make both about the counterparty and about themselves as negotiators. They also explored a number of frameworks to understand the context, and developed repeatable and reliable strategies to overcome these limiting beliefs to reach positive negotiation outcomes

Negotiation is a fundamental element in the social life of organizations. Whether you are aware of it or not, you negotiate for resources and attention. Research in social psychology and behavioral economics has uncovered key principles that can help you become a better negotiator. Although the science of negotiation has developed rapidly in the last two decades, aspects of negotiation are an art.

Dealing with cognitive biases

People’s rational and irrational selves compete with each other constantly. Psychologists use the metaphor of “the elephant and the rider” to refer to these two parts of the human mind. The elephant is the irrational intuition that takes you to places you may not even be aware of, and the rider is the rational cognitive mind. Although the animal is physically stronger, you as the rider can control it because of your ability to process information and condition the elephant. However, rational reasoning takes time and effort, while the intuitive system is fast and occurs in parallel, without any effort.

Cognitive biases that affect negotiation behavior reside within the irrational intuitive system. In an effort to understand these biases, participants worked on a negotiation exercise that involved coming to a collective decision. By deconstructing the decision-making process, it is possible to uncover how biases creep into conversations. These include:

- Anchoring: People tend to build an initial position based on the available information. Even when new information comes through, it is hard to move away from that “anchor” position. In negotiation conversations, the initial position becomes a very strong anchor. This is why the first offer is always “sticky” – in an uncertain situation, people hold on to what is certain, i.e. the anchor. The greater the complexity of a negotiation, the stronger the anchoring.

- Framing: A given situation can be framed as either a gain or a loss. If you view a negotiation from a gain frame, it makes you risk averse; if you focus on the potential loss, you become risk seeking. Risk is a feature of the context and you can create the context. A classic example of loss framing is when health insurance sellers emphasize the downside of not taking a particular policy.

- Confirmation bias: This comes from a sense of self-protection and a desire to confirm your hypothesis. Having made up your mind, you look for information that proves you right; rarely do you seek information that proves you wrong. The intuitions of experts can be useful as they provide a hypothesis, or base, to work from. In organizations, sometimes intuition does not reside in the higher levels of the hierarchy but at the frontline, where employees pick up signals that have not yet been translated into parameters. Such hypotheses should then be validated with existing data or by conducting fail-fast experiments to simulate the data.

- Availability bias: This involves acting based on the information readily available in your memory, which is generally biased toward vivid, unusual or emotionally charged examples. Things in recent memory tend to overly influence decisions. Often, leaders think of causality based on a small number of use cases, whereas statistical causality requires a much larger sample size.

Biases do not recede when the stakes are high. And time pressure (a classic negotiation strategy) amplifies them. All these biases are unconscious, and over- coming them is hard. Potential remedies are to embrace diversity in a team and to create structure by cultivating a balance between enquiry and advocacy (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Balancing enquiry and advocacy

Claiming value in a negotiation

The approach to claiming value depends on whether it is a distributive or an integrative negotiation process. Distributive negotiation is a fixed- sum game where one person’s gain is another person’s loss. In such a scenario, there are directly conflicting interests, and each party attempts to maximize his or her share of the payoff. The challenge in simply dividing the “pie” is that the two parties generally do not know exactly how large it is. In these negotiations, first offer is the most sticky and therefore critical in terms of the timing and precision. Research shows that precise first offers are more sticky, as long as there is a logic for the precision. Making a first offer is risky when you lack knowledge. It is essential to build some rapport before making an offer.

Extreme offers, however, damage relationships. The relationship capital is depleted when the first offer is outside the bargain zone. Often, an extreme first offer is a bait. The more time an extreme opening offer has to justify itself, the more the counter-party is baited into the offer.

One way to deflect an extreme offer is to make a counter offer. Another way is to dismiss it outright as an inappropriate starting point for a conversation: “Let us take some time to evaluate and reconvene when we have a better starting point.” It is important to recognize that an extreme offer makes the recipient uncomfortable, but he or she can consciously decide to become comfortable with that discomfort.

Three essentials

Before entering a negotiation, you need to assess three things: your goals, your best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA), and the reservation price.

The goals should be quantitative and precise, and the negotiator must be held accountable for them. They must be somewhat difficult to achieve and must be recalibrated over time. A caveat is that “reaching a fair agreement” is nota goal. There is no such thing as dividing the pie fairly because fairness is not an objective metric. If the counter party does better than you do, you feel it is unfair even though you may have achieved your goals.

BATNA is the alternative to the deal if you cannot come to an agreement. The reservation price is the walkaway point that you will not breach and which you cannot reveal at any cost. For an outcome lower than the reservation price, no agreement is preferable. The final deal is usually secured between the goal and the reservation price. The bargaining zone is the space between the buyer’s and the seller’s reservation price. The zones must overlap for a possible agreement. While the BATNA is your source of power, you also have to assess your counterpart’s goal, BATNA and reservation price.

Concessions

Often, concessions are made in the course of a negotiation. A clear rationale must be developed for each given concession. Moreover, concessions must always be reciprocated. If you make unilateral concessions in a negotiation, you will end up on the losing side. The value of the concessions must go down with time; you should not be making large concessions toward the end of a negotiation because then you are giving away value.

Closing the deal

One tactic for closing deals is to split the difference, i.e. meet in the middle, especially if the differences are small. Another way is to throw in a sweetener at the end. But it should not breach the reservation price. Sometimes the counter party asks for something towards the end; that is not a sweetener – that is a “nibble.” A sweetener is voluntary, whereas a nibble is forced. The only way to deal with a nibble is to nibble back.

Sometimes one party may “assume the close” and behave as though the deal is done. It is important to be aware of whether you are really in agreement or you are signing out of politeness because the other party assumes the deal is done.

In some negotiations, ratification is used as a deliberate strategy, i.e. when the deal is almost done, the counter party says they have to check with their boss. Therefore, before starting negotiations it is important to check who the decision maker is. When you are dealing with a large organization, you may never see the ultimate decision maker. In such cases, you may have to factor a buffer into your calculations as you can expect a nibble at the end.

Deciding who in an organization will negotiate has to be an informed choice because the power dynamic will emerge in a negotiation. If you want to develop a relationship, it is better to match the level of the negotiators or even go one step higher.

A commonly used tactic to create pressure is an ultimatum – take it or leave it! But if you don’t mean it, you will lose credibility. Ultimatums have to be diffused or ignored by using a trade-off mindset; if you react to an ultimatum then you escalate matters. Negotiation conversations take place at three levels: interests are at the core, followed by rights and finally power. To keep your composure in the face of an ultimatum, you need to keep coming back to your core interests (goals).

Creating value in a negotiation

To achieve a win-win in an integrative negotiation, the two parties must have different preferences. An applicable metaphor is that of baking a cake. The more information (or ingredients) you share, the bigger the cake you bake. If you give more information, however, you could end up with a smaller share as your information can be used against you. But if you hold back, you bake a smaller cake. This is the classic negotiator’s dilemma: to achieve a balance between creating value and claiming value. This is because the strategies that create value actually hurt claiming value and vice versa. Negotiation therefore becomes an art.

Win-win, not compromise

To achieve win-win, both parties must be motivated to create value. Discovering value takes time and significant engagement with the problem. You need to be resistant to yielding, i.e. you cannot give up too quickly. Meeting half-way is compromise, and compromise is not win-win.

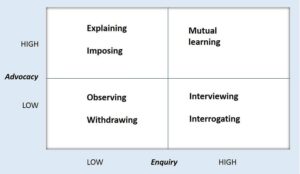

The biggest barrier to win-win is assuming that the other party wants the same as you – the fixed pie perception. Another barrier to creating value is saying that something is non-negotiable (to gain the upper hand). Not every situation is a win-win negotiation. Win-win paradoxically requires a simultaneous concern for self and the other, which ultimately leads to collaboration (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Getting to win-win

Widening the scope

You are more likely to find win-win by increasing the scope of the negotiation. Adding issues to expand the conversation and looking for different preferences enhances the potential to create more value. An important tool for controlling the negotiation process is MESO or Multiple Equivalent Simultaneous Offers, i.e. you can create multiple offers that have the same notional value for you but they may be viewed differently by the other side. When you suggest these offers, depending on what the counter party picks, you can learn what is important for them.

A unique method for creating value is a PSS or Post-Settlement Settlement. After a deal is struck and signed (such that it is binding), both parties may decide to revisit it and see if they can do better. It is not a reopening of the negotiated deal, but the absence of pressure allows them to think creatively. It requires a certain level of maturity and trust. Whether the outcome from the PSS is integrated into the original deal is a matter of choice for both parties.

Power and negotiations

The psychological effect of power is that it makes people self-focused and overconfident, and increases optimism and the tendency to stereotype others. Power also increases the likelihood of taking action, irrespective of whether it hurts or helps. The role of power in negotiations can be illustrated with a clip from the US TV show “Shark Tank,” where entrepreneurs pitch their ideas to investors in the hopes of gaining funding for their company. Participants placed themselves in the shoes of an entrepreneur and shared their strategies for negotiating from a position of low power. After viewing the negative outcome of the actual deal, they analyzed what had gone wrong with the negotiation – applying concepts like goal setting, avoiding a non- negotiable stance, and missed opportunity for loss framing – and what could have been done differently. A counterintuitive insight was that sometimes having a little power could be worse than having no power at all; no power could trigger the benevolence of the powerful player.

Negotiating at work

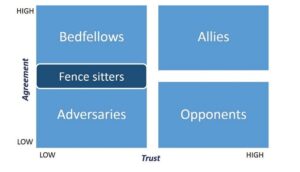

How should you deal with people in your own company? A framework can help assess the roles of colleagues along two dimensions – trust and agreement (Figure3). The trust axis is more static; the agreement axis can shift depending on the issue.

- Allies are high on trust and agreement, and you can also expose your vulnerability to them. It is useful to ask allies for advice on difficult problems, but you must follow through. Using allies as a third party to influence others is a powerful way to conduct intra- organization negotiations.

- Opponents are the most important people to nurture – you trust them but they disagree with you. This positive conflict helps to generate superior ideas. You can go to your opponents to find disconfirming evidence.

- Bedfellows are low on trust even though they agree with you. Reciprocity is what holds this relationship together. One blind spot is to mistake a bedfellow for an ally.

- Fence sitters can be used as challengers/opponents by providing them with data that will enable them to take a stance. It is important to change the position of fence sitters when implementing a change initiative – or you might get surprises.

- Adversaries tend to take up a lot of time and energy; it is possible to become obsessed with converting them into allies. While you may not be able to convert them, third parties can. If an adversary is a make-or-break stakeholder for your initiative, working on them through their allies might bear fruit.

The people you trust and who disagree with you are worth their weight in gold.

Participant

Figure 3: Intra-organization framework

Negotiators of the future – bots

In a recent Facebook Artificial Intelligence Research experiment, two bots – Alice and Bob – using natural language processing negotiated much harder than humans and used strategies such as feigning interest to get to a better deal. In fact, using AI, the bots started creating their own language with a different structure that even the researchers could not understand. The experiment was ultimately stopped because it had run its course. But the patience and determination of bots could definitely pay off in negotiations of the future.

Discovery Events are exclusively available to members of IMD Nexus. Learn more about IMD Nexus