However, this is the powerfully appealing and incredibly dangerous siren song of the status quo. This undue focus on win-wins doesn’t get us to where we collectively need to get. It allows us, as leaders and humans, to avoid the most important questions about ourselves and the roles we take on inside organizations.

Our obsession with win-wins

In the business press and at business schools, it’s all about the “win-wins” and “socially responsible business”. Our business magazines (including this one) and business school cases are filled with heroic leaders creating business models that are environmentally sustainable and profitable.

They tell us (sometimes rightly) that by, say, serving the bottom of the pyramid, or differentiating our products through their sustainability bona fides, we can be profitable. And the same outfits assert (nearly always falsely) that acting responsibly is necessary for long-term financial success.

Take the example of Ray Anderson, CEO of carpet company Interface, who describes in a TED talk his moment of environmental awakening which felt like a “spear to the chest”. He had thought of himself as a titan of industry, he says, but suddenly saw himself as a “plunderer of the earth”. His company, he came to admit to himself, was gaining its profit at the expense of the planet. He then relates how he dedicated himself to changing its business model to be more circular and sustainable. The TED site gushes in its blurb about the video, “At his carpet company, Ray Anderson has increased sales and doubled profits while turning the traditional ‘take / make / waste’ industrial system on its head.” There it is again: the ubiquitous story of doing well by doing good.

His story is an inspiring and honest reckoning, and I’d recommend a listen. We should learn from it and we should look for win-wins. This is largely what you, as a business leader, are paid to do. And as a strategy professor, helping leaders and managers identify and implement win-wins is what I am paid for.

And yet, there is an uncomfortable rub of Anderson’s success story: it is noteworthy because it is necessarily rare. For most firms, doing what is required to achieve 100% sustainability in our current regulatory contexts and competitive environments would be unprofitable. Given the path dependency of their investments and competencies, for most firms being deeply environmentally unsustainable may be their only path to the continued profitability that is demanded by the larger power and ownership systems that control them.

In some ways, stories like Anderson’s recall fairy tales: they inculcate us with the belief in the ultimate fairness of the universe, suggesting that we can do what is right and heroic, and that doing so will redound to our—and our companies’—benefit.

But this happy tale is, of course, at best only a half-truth. Justice does not reign. Children die of malaria, jerks get promoted, wealth and opportunity get unfairly distributed at birth, and billions of sentient beings suffer and die because we like how they taste. My salary comes from a business school which prides itself on its focus on sustainability but has its client-executives fly in by the thousands. Nearly all of us are morally compromised.

So why, then, do we collectively focus on these win-wins if they are the exception rather than the rule? First, there is an important social benefit to doing so: These stories provide role models for positive action and may inspire and motivate readers to reach for similar win-wins, which are so important for our collective future.

Secondly, these stories help meet a deep psychological need. Believing that the world is fair and tending toward progress simply feels good; looking too much at the uglier alternative risks a deeply depressing nihilism and defeatism.

For these reasons, I wouldn’t advocate eliminating exemplary business stories of doing well by doing good any more than I would advise raising our children on a diet of Nietzsche. Nonetheless, there are serious costs to focusing too much on the win-wins.

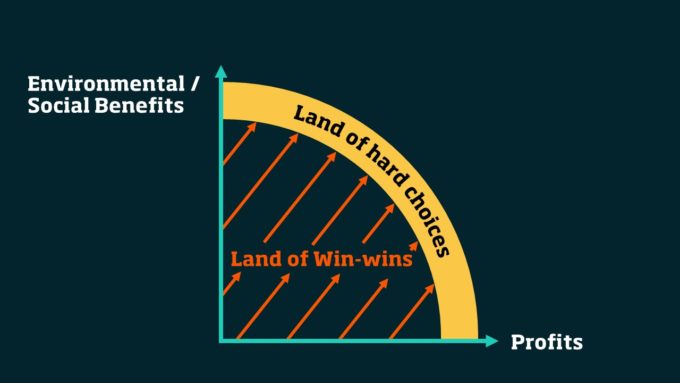

Moving from the land of win-wins to the land of hard choices

Smart managers seek to identify and implement win-wins. This “land of win-wins” is all about novel business models, innovation and efficiency gains. As regulation, technology and the cultural zeitgeist all shift, this space is enlarging. This is a huge and exciting space, and we need to push it vigorously.

Audio available

Audio available