Unexpecting the expected to adapt to a changing world

In volatile, fast-changing, and complex situations, received wisdom and expertise can become a liability that’s hard to overcome. Here are seven ways to change your mindset....

Audio available

by Goutam Challagalla Published August 1, 2023 in Strategy • 7 min read

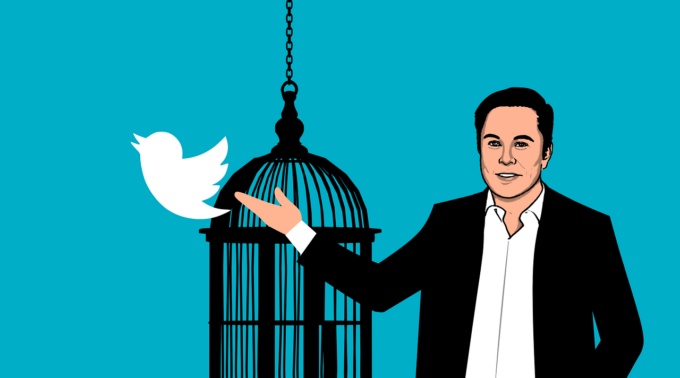

When Elon Musk announced in late July that the social media platform Twitter would scrap the blue bird logo and replace it with a black X, the decision was widely mocked on social media with some analysts saying the billionaire has potentially wiped out between $4 and $20 bn in brand equity built up over 15 years. After all, very few businesses can boast that a word associated with their company name has become part of the language, in a way that “tweet” has morphed into a byword for online communication.

Musk is far from the first corporate titan to decide that his company needs a makeover. A change in ownership is often one trigger for a rebranding, as is a decision to expand product and service offerings in a new direction, or to remove negative associations connected to the old brand. Musk could arguably have been motivated by all of the above.

Here, I examine some of the main reasons for rebranding through the lens of companies that have successfully made the change, as well as those who have failed.

One common reason companies change their name is to distance themselves from negative associations related to a product or event. This was the case for Phillip Morris, which rebranded as Altria Group in 2001, to shake off the negative associations with tobacco products and emphasize that it has diversified into other industries like food and beverages.

Such moves can, however, backfire. In 2000, oil major British Petroleum rebranded as “Beyond Petroleum” to signal its foray into renewables. But the move was widely criticized after BP continued to be responsible for oil spill disasters and the rebrand was ultimately abandoned after most of its investments into wind and solar over the next decade failed.

At Twitter, Musk, who has openly called out the platform for being biased against conservatives may feel that a name change might broaden its appeal to different audiences by removing the association of being too left wing.

Many companies decide to rebrand because their name is so associated with a certain service or product that it restricts their ability to go off into a new direction. This has been a common route for auditing firms who have expanded from the traditional accounting services for which they were known into business consultancy. PricewaterhouseCoopers rebranded to PwC while Ernst & Young became EY.

Another famous example is Google which has a powerful consumer brand associated with the eponymous search engine. In 2015, Google restructured its corporate identity and created a new parent company, Alphabet, which oversees various businesses including Google. The change allowed Google to focus on its core search and advertising business, and differentiate its other ventures, such as life sciences firm Verily and autonomous driving business Waymo among others. It also introduced more accountability and transparency into its structure for investors and allowed it to be taken more seriously in its non-core areas.

Other companies may find that new products and services are overshading the original business after which they were first named. This was arguably the case for Facebook, which rebranded as Meta in 2021, and owned Instagram and WhatsApp, both strong brands in their own right. The name change to Meta also signaled CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s belief that the way we interact with one another will shift into an alternate reality, or the Metaverse, in the future.

One risk is that the name change may fail to resonate with customers. In 2007, US electronics retailer RadioShack rebranded as “The Shack” in a bid to make it sound more relevant in the digital age. However, the change didn’t go down well, and the company eventually filed for bankruptcy.

When companies combine or split up this often triggers a corporate name change.

Hewlett Packard acquired Compaq in 2022 and combined the power of their brand names to form “HP Compaq” to leverage the recognition and reputation of both companies. After AOL merged with Time Warner, the combined company changed its name to AOL Time Warner. However, the name change was eventually reversed back to AOL after the merger ran up against significant challenges to reduce the harm to the brand.

Another reason is to establish a more uniform identity among a bunch of unrelated firms that have been acquired over time. D.G was an Italian holding firm, which had grown from a motorcycle production company into an industrial packaging company through multiple acquisitions. However, each of these businesses was just operating on its own and there was no uniformity. By grouping all these companies under the name Coesia in 2005 they established a common identity and shared values.

When a company breaks up, it often faces the question as to whether to keep the name of the parent company. In 2021, German automotive company Daimler decided to split into two companies, spinning off its commercial business into Daimler Trucks and renaming the part that focusses on passenger vehicles the Mercedes-Benz group after the name of its well-known car.

What is evident is that rebranding is always about choice. While there is often no single reason for a rebrand, by changing their names, companies have to be aware of what the move signals about its future direction and what they are sacrificing as a result.

Some companies can have the luxury of being associated with many different brands. This if often true for consumer groups like Nestlé and Unilever which are home to many well-known businesses in their own right and it makes little sense to be associated with just one.

Other organizations will elevate one brand to become the name of the parent company while keeping the others. Online travel agency Booking Holdings renamed itself from the Priceline Group in 2018 after its popular brand bookings.com even though it also owns Kayak, Agoda, Priceline, and OpenTable among others.

So why didn’t Musk keep Twitter’s brand name, and launch additional products?

The change to X fits with Musk’s goal to turn the platform into an “everything app” modelled on China’s WeChat. The company’s CEO Linda Yaccarino has outlined the company’s vision for X to become a site for audio, video, messaging, payment, and banking.

It is possible that Musk felt the Twitter brand, was too established as a social media platform, and could act as a straitjacket on his bigger vision.

Critics have described the rebranding as a mistake since the name had come part of the modern culture with verbs like “tweet” and “retweet” part of everyday language.

Yet, Musk may have considered these benefits to be overblown. After all, the fact that we used to say “xerox” to signal that you were photocopying something didn’t stop the company’s decline after it failed to capitalize on growth opportunities in the digital age. In a similar vein, we might soon start using “ChatGPT” as a verb just like we use “google” today.

While there’s no doubt that there is massive value to a strong brand, particular one that can trigger certain emotions like Apple and CocaCola, Twitter’s strength is also in its user base and limited competition. Despite Meta’s recent launch of Threads there aren’t that many social media platforms in the world.

For companies that have this kind of power, a name change is simply less of a risk.

Professor of Marketing and Strategy and dentsu Group Chair in Sustainable Strategy and Marketing at IMD

Goutam Challagalla is Professor of Strategy and Marketing and dentsu Group Chair in Sustainable Strategy and Marketing at IMD. His teaching, consulting, and research focuses on strategy with a focus on digital transformation, business-to-business commercial management, value-based pricing, sales management, distribution channels, and customer and service excellence. At IMD, he is Director of the Advanced Management Program (AMP), Digital Marketing Strategies (DMS), and Strategy Governance for Boards, and co-Director of the Integrating Sustainability into Strategy.

19 hours ago • by Martin Fellenz in Strategy

In volatile, fast-changing, and complex situations, received wisdom and expertise can become a liability that’s hard to overcome. Here are seven ways to change your mindset....

Audio available

Audio available

July 14, 2025 • by Richard Roi in Strategy

Kevin O’Brien shares the lessons every first-time CEO needs to hear-from unpacking the brief to unlocking future potential and uniting the team....

July 8, 2025 • by Alyson Meister, Marc Maurer in Strategy

Marc Maurer shares how ON grew from startup to IPO by defying hype, focusing on purpose, and leading with humility in this candid Leaders Unplugged episode....

June 26, 2025 • by Michael Yaziji in Strategy

Forward-thinking leaders proactively shape their external environment, turn uncertainty into certainty, and create substantial value in the process....

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience