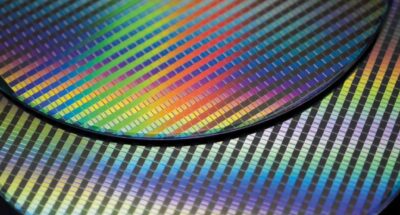

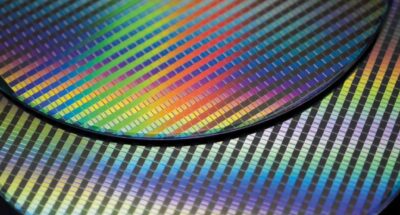

Europe needs Chips Act 2.0 to compete in digital race

Former French finance minister Bruno Le Maire says Europe needs to act urgently to secure its supply of semiconductors or face relegation to the global slow lane. ...

Audio available

by Jerry Davis Published September 20, 2024 in Talent • 8 min read •

Are we living in a simulation? Might we be merely avatars in a cosmic video game? This seemingly fanciful question has animated thinkers from Lana and Lilly Wachowski (makers of the 1999 classic The Matrix) to Silicon Valley types today. Questions like this are catnip for a recovering philosophy major like me.

One place where reality seems increasingly like a simulation is the labor market. Since the COVID-19 pandemic drove tens of millions to work or attend school from home and millions more to take on algo-driven gig work such as food delivery, labor has become increasingly intermediated online. From AI job interviews to work-from-home gigs to mass layoffs via Zoom calls, the basic transactions of work happen through a screen for much of the population. Many workers today have never set foot in their employer’s establishment or been in physical proximity to their boss or co-workers.

The virtualization of the workplace corresponds to a decline in economic mobility. It’s hard to plan a career path in a world where every job is a gig and faceless algos are the boss. It’s even harder when intermediation can easily slip into deception.

I got my first job in 1978 as a busboy in a restaurant near my home. My job involved setting and clearing tables and “bussing” the dirty dishes to the dishwasher. I showed up at the front desk of the restaurant one afternoon, filled out a one-page paper application, and took a seat. A few minutes later, the manager escorted me to her office for an interview. “Why do you want to be a busboy?” she asked. I replied confidently: “Because I have always dreamed of carrying plates.” I was hired immediately and started my career journey at $2.65 an hour.

The job recruiting process today bears little resemblance to my experience. For one thing, it rarely involves human interviewers anymore. Everyone today is expected to have some version of a standardized online resume, and the odds are excellent that a human will never see your application. Instead, evaluating applications (and writing job descriptions) is largely done by AI-powered bots who can screen thousands of applicants in minutes to select interview finalists.

Some applicants respond to this by using “white type” as a hack to get past the screening algo: cutting and pasting keywords from the online job description onto their resume in white one-point font that is invisible to humans but perfectly legible to the resume-scanning bot, in the belief that this will whisk them to the top of the pile based on their perfect fit with the job. (Exasperated recruiters claim that this does not, in fact, work.)

If you make it past the initial screen and get an interview, you will likely encounter another AI algo. Recruiting software vendors enable HR offices to conduct virtual interviews by posing standard questions to applicants who record their answers remotely on their computer video. Typically, candidates get two chances to record responses to each question before submitting their video for evaluation – again, most likely performed by an algorithm.

“Silicon Valley has long lived by the creed 'Fake it till you make it'. Theranos, WeWork, and plenty of other enterprises exemplify how this loose relation to reality can continue for extended periods.”

The real fun begins for those who move past the first round or two of robo-interviews. Applicants may have to endure round after round of tests, tasks, and additional interviews, potentially lasting days. A cynic might imagine that some interview tasks – “create a social media campaign for this upcoming event” – might be a scam to get free work. Regardless of the effort applicants put in, there is no guarantee that they will ever hear from the employer again. Applicants report being ghosted by employers after putting in hours to the application process.

Worse still, the job you are applying for may not exist. One recent survey of hiring managers suggested that an unknown number of online job listings are for openings that are not really there. Three in 10 employers surveyed recently reported hosting fake job listings on their sites. Why would employers list non-existent jobs and waste the time of applicants? Some aim to convince existing employees that business is robust and the company is growing – or that they can be replaced. Others are simply testing the waters to see what talent is available. Either way, plenty of talented applicants are guaranteed disappointment; conversely, “hiring” managers report that fake job listings improve morale and productivity among existing employees.

If you get the job after surviving the Kafkaesque gantlet of the contemporary job search process, you might face an ever-receding start date in a city you did not expect to go to – or a layoff based on ChatGPT replacing you sooner rather than later.

The labor force is not entirely powerless in this situation. AI-based interviews have prompted an arms race in which applicants have their weapons: generative AI apps that listen to interview questions in real time and propose well-informed responses that interviewees can recite to ace the interview. With one laptop asking questions from an AI script and another proposing AI-generated answers, the applicant is essentially reduced to an intermediary reading a script from a teleprompter.

Inevitably, in a world of work-from-home, some people have taken to outsourcing their jobs. It’s easy to find talented remote workers on Upwork and other platforms at low cost, and if they can do the work almost as well as you can, why not engage in some arbitrage? Some skilled jugglers manage to hold multiple remote jobs by subcontracting out work. As long as they can turn up for the Zoom meetings and pretend to pay attention (or hire a suitable front), why be limited to just one job?

Of course, there is no reason why the Upwork contractor might not further subcontract the work to their own shadow workforce. There is a thriving sector of “labor dropshipping” on TikTok in which contractors with good language skills and negotiation savvy serve as the virtual brand, managing a portfolio of subcontractors. On the internet, nobody knows you’re a sub-sub-subcontractor.

The high water mark of all this virtual organization may be Madbird, an alleged global digital design agency “housed” in London that went on a hiring spree during the height of the COVID-19 lockdown, recruiting over 50 professionals – mostly in sales. These “employees” were brought on board with the understanding that they would be paid only on commission for the first six months, after which they would receive a salary. Remote workers joined all-hands meetings on Zoom with dozens of colleagues boasting impressive LinkedIn profiles and testimonials from prestigious global clients – but with their cameras off. The company’s website featured photos of an elaborate organization chart full of talent, led by an Internet-famous influencer claiming a world-beating career at Nike. It also listed a swanky Kensington address for its headquarters.

It was all a mirage. Photos of fake employees were downloaded from the web, LinkedIn profiles and testimonials were fabricated, and client testimonials were whole-cloth creations. As documented by the BBC, Madbird had no clients, revenues, or offices – but dozens of unpaid workers, many of whom had quit real jobs to work for the vaporous agency.

Silicon Valley has long lived by the creed “Fake it till you make it”. Theranos, WeWork, and plenty of other enterprises exemplify how this loose relation to reality can continue for extended periods. But Madbird took it to a new level, like an MFA thesis gone horribly wrong.

The 20th-century job market had a clear structure for upward mobility and a clear metaphor: the career ladder. The pyramid-shaped organization chart may have looked like a prison of conformity, but it was clear which way was up, and corporate HR offices expended great efforts to provide legible steps to climb the ladder. Today’s labor market gives us few clues as to how to move ahead, and yesterday’s career wisdom – “learn to code” – can have a very brief shelf life. We may as well be living in a simulation – and it is not at all clear where to get the cheat codes.

An underlying theme of this column is that information and communication technologies (ICTs) have dramatically changed the transaction costs for accessing the basic building blocks of business. For suppliers, this looks like Alibaba: a one-stop shop for finding manufacturing vendors. For distribution, it looks like Fulfillment by Amazon: a universal distribution channel for physical goods.

However, in labor markets, the transaction costs and risks have merely been shifted from business to labor. Candidates may spend countless hours completing courses for LinkedIn badges, researching companies, prepping for video interviews, undergoing multiple rounds of testing and completing tasks – all for jobs that may not exist at companies that may turn out to be vaporware. If we are living in a simulation, many of us are ready to declare game over.

The online mediation of labor markets may seem like a boon for employers who contemplate outsourcing their HR function to a bundle of algorithms able to optimize their supply of talent. The costs to workers, however, are increasingly manifest: unpredictable incomes, endless rounds of retraining with uncertain payoffs, shotgun applications to dozens or hundreds of employers, and hours spent pursuing opportunities that may exist only in an illusory jobs board. At the dawn of the online economy, we imagined remote tech workers coding on the beach while slurping a cocktail. Today, navigating employment can seem like a miserable video game with unclear rules and buttons that don’t work.

Adding to the puzzle is that the tools we have relied on to map our labor markets no longer work. Response rates to government surveys of workers and employers are sometimes below 50%, the occupational categories used to describe the jobs people hold no longer fit a world in which new roles come and go at an increasingly frantic pace, and the job listings used to assess the abundance of employment opportunities are filled with rampant falsehoods.

It is past time for governments to create a 21st-century framework to provide stability, predictability, and honesty in the job market and to enable workers to have a fair shot at economic mobility.

Professor of Business Administration and Professor of Sociology, University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business

Jerry Davis is the Gilbert and Ruth Whitaker Professor of Business Administration and Professor of Sociology at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business. He has published widely on management, sociology, and finance. His latest book is Taming Corporate Power in the 21st Century (Cambridge University Press, 2022), part of Cambridge Elements Series on Reinventing Capitalism.

July 10, 2025 • by Bruno Le Maire in Magazine

Former French finance minister Bruno Le Maire says Europe needs to act urgently to secure its supply of semiconductors or face relegation to the global slow lane. ...

Audio available

Audio available

July 8, 2025 • by Mike Rosenberg in Magazine

A new framework encourages leaders to see the world as PLUTO – polarized, liquid, unilateral, tense, and omnirelational. It’s time to think differently and embrace stakeholder capitalism....

Audio available

Audio available

July 3, 2025 • by Eric Quintane in Magazine

Entrepreneurial talent who work with other teams often run into trouble with their managers. Here are ways to get the most out of your ‘boundary spanners’...

Audio available

Audio available

June 26, 2025 • by Michael Yaziji in Magazine

Forward-thinking leaders proactively shape their external environment, turn uncertainty into certainty, and create substantial value in the process....

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience