“We were so scared of our IPO”: Leaders Unplugged with former On-CEO Marc Maurer

Marc Maurer shares how ON grew from startup to IPO by defying hype, focusing on purpose, and leading with humility in this candid Leaders Unplugged episode....

by Michael D. Watkins, Wendy Behary Published May 31, 2021 in Leadership • 9 min read

Learning to anticipate and mitigate damaging emotional patterns is important, but so is resetting expectations, write Wendy Behary and Michael Watkins.

Early in a meeting to discuss marketing strategy, Daniel, the VP of Marketing, interrupted his CEO, Paul, who had launched into a typically long-winded explanation of why his view of the way forward was the right one. Daniel had long struggled to win Paul’s approval and had spent significant time collecting and analyzing some new data that largely supported Paul’s viewpoint. However, rather than welcoming the new input, Paul became visibly angry at being interrupted, and the rest of the room thought “, here we go again.”

Pausing to shoot a disapproving look at Daniel, Paul pushed on as if nothing had happened. Visibly wounded, Daniel sat back in his chair, mumbling an apology and looking resentful. Reading the reaction among the rest of his executive team and feeling that he had contributed yet again to causing an uncomfortable scene, Paul directed dismissive comments at Daniel, casting responsibility for this “unhelpful interjection” onto him. Daniel responded by defensively trying to rationalize his decision to introduce the new data, only to be cut off and told to “stick to the agenda.” The meeting ended with everyone in an unsettled state and little accomplished.

In our work with top executives and their teams, we often observe scenes like this and listen to our clients recount them. These sorts of unproductive interactions are both common and damaging. In the case of Paul and Daniel, both emerged from the meeting angry and resentful, setting the stage for further strife between them and lost opportunities to move the business forward.

Why do poisonous dynamics like this take hold? In many cases, it’s because leaders and their subordinates are locked in the grip of maladaptive emotional patterns that, when triggered, show up as dysfunctional modes of behavior. Even the best leaders sometimes can fall into these derailing modes of leadership, especially when under stress. Only by understanding these patterns and learning to identify and manage them can they hope to lead and follow more productively. The key to doing so lies in understanding and applying the tools of Schema Theory.

Schema Theory is an integrative school of psychotherapy, developed by Dr. Jeffrey Young and his colleagues in the early 1990’s and practiced worldwide. It combines elements of cognitive-behavioral therapy (which focuses on correcting biased beliefs and altering self-defeating behaviors), and interventions focused on healing early emotional trauma. Extensive research established its efficacy with some of the most difficult-to-treat psychological syndromes, such as personality disorders and chronic mood disorders. It also turns out to have profound implications for understanding why dysfunctional leaders do the things they do.

Where do these deeply rooted patterns – called Early Maladaptive Schemas – come from? In most cases, it’s from early childhood experiences of not having basic needs met. Every leader once was a child, and like every child depended on others to get basic needs for safety and attachment met. When those needs were not met, for example, through abuse or neglect, or when getting parents’ attention or approval depended on behaving in specific ways, for instance, being perfect at doing things, getting high grades at school, or winning at sports, then deep patterns of behavior get established. Early experiences of abuse, for example, understandably result in a propensity to be mistrustful, and constant pressure to perform can lead to a need to be perfect.

The importance of Schema Theory in understanding and shaping leader behavior resulted from early conversations we had about the challenges Michael was facing in coaching some senior executive clients. For this subset of clients, conventional coaching methods failed to positively impact what appeared to be deeply ingrained patterns of dysfunctional behavior. While these leaders responded somewhat to feedback from psychometric or 360 assessments, they ultimately seemed unable to realize more than temporary change. Helping them appeared to be more the province of therapists than executive coaches.

At the same time, a substantial subset of Wendy’s clientele were people in senior leadership positions who entered therapy because of serious issues in their personal lives, such as divorce or estrangement. In our conversations, we explored the intersection of our two professional worlds and the potential for Schema Theory to provide insight into dysfunctional leader behavior and new strategies for executive coaches.

Ultimately, we concluded that many executives operate in the “shadow” of their early maladaptive schemas in ways that profoundly undermine their effectiveness as leaders. For Paul, his volatility and bullying behavior left everyone who worked for him “walking on eggshells” and unwilling to challenge him, even when it was clear he was wrong. For Daniel, his constant need to seek recognition and approval prevented him from “showing up” more powerfully and effectively.

This has significant implications for the behaviors of leaders. When triggered, Early Maladaptive Schemas can cause people to shift into self-defeating modes of behavior like those experienced by Paul and Daniel

To explore this further, we began by seeking to understand the prevalence and impact of schemas and corresponding dysfunctional modes of leader behavior. Based on existing questionnaires created by the practitioners who developed Schema Theory, we constructed a questionnaire focusing on ten schemas we hypothesized were likely to influence executive leadership. We sent the questionnaire to a sample of former participants in a 4-week executive leadership program at the IMD Business School, getting 55 responses. Analysis of the data showed that the leaders reported significant frequencies for three of the ten schemas we selected, as shown in the table below. The schema with the highest frequency was “Unrelenting Standards,” with almost 50% of the respondents indicating that it was Mostly or Completely True that they exhibited the associated behaviors.

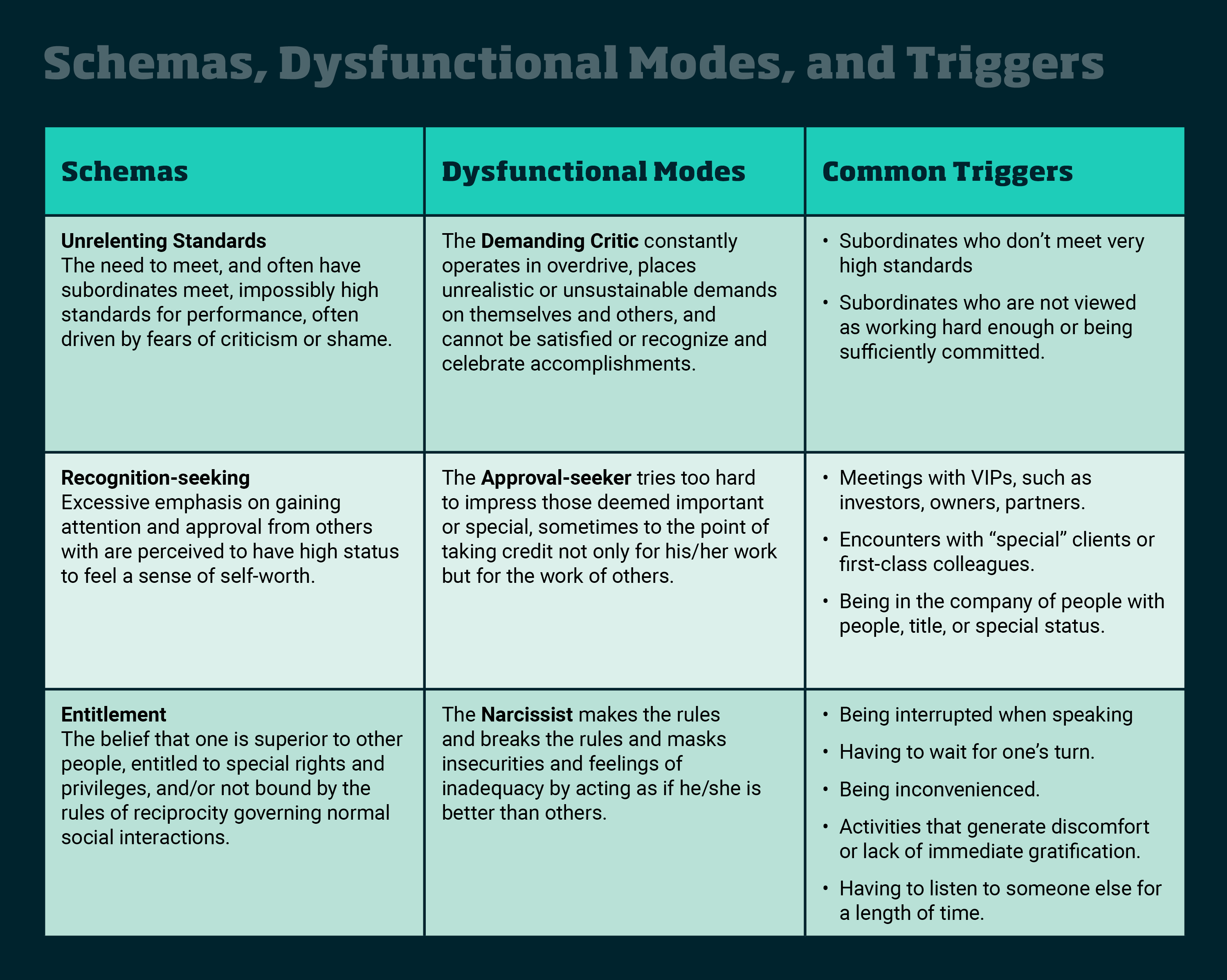

Unrelenting Standards is the need to meet impossibly high standards for performance. The Unrelenting Standards schema often shows up as an internalized “voice,“ reminiscent of a demanding parent. It drives you to hold yourself (and often the people who work for you) to impossibly high standards. (See, “Do You Have Unrelenting Standards?“) Recognition-seeking is an excessive focus on gaining attention and approval from others with are perceived to have high status. Entitlement is the belief that one is superior to other people, entitled to special privileges, and/or not bound by the rules of reciprocity that govern regular social interactions.

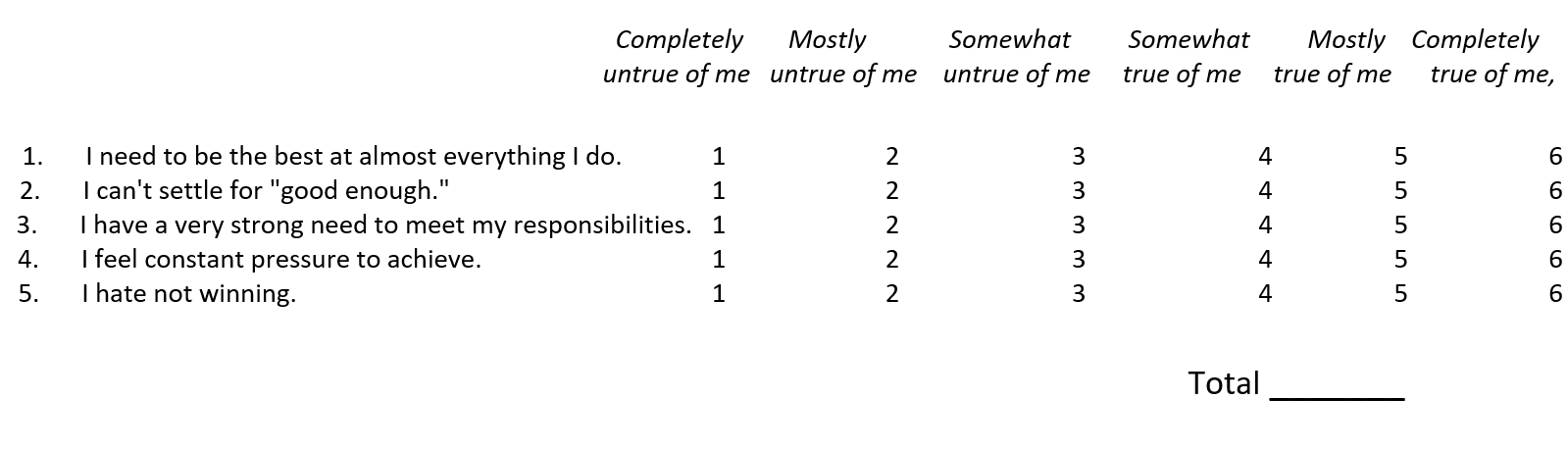

To see if you have the Unrelenting Standards schema, answer the questions below, Circle the responses that best capture you, and sum your responses for the five questions. If your total is greater than 20 and/or you answered two or more questions with 5’s or 6’s, you probably do.

Schemas can lie dormant until they are “triggered” by specific events (sensory experiences, social interactions, the behaviors of others) that lead to their activation. Schema activation triggers a shift from one emotional mode to another, potentially maladaptive one, for example, from a calm, encouraging state to a highly demanding state.

Leaders often have a relatively small set of schemas and a corresponding set of modes through which they cycle over time. Paul, the CEO mentioned in the story at the start of the article, did have a “Healthy Adult” mode (wise, emotionally accessible, reasonable, rational, thoughtful) in which he operated a significant amount of the time. He also had a “Demanding Parent” mode (with unreasonably high expectations and rigid standards) into which he shifted when he thought subordinates were underperforming.

There is a strong correspondence between the three schemas we identified as most common in the leaders we studied and a corresponding set of dysfunctional modes (See, “Leader Schemas, Modes and Triggers”). While having one of the three schemas doesn’t guarantee that you will exhibit the corresponding dysfunctional leadership mode, it’s likely. If you do, the shift into these modes will happen due to specific triggers, which are very important to understand and learn to manage.

Leader’s schemas can get triggered by the actions of their subordinates – which can be the result of their schemas and modes getting triggered. The result can be “schema clashes” that can be highly damaging. Daniel, the Marketing VP in the story at the start of the article, had a “Recognition-seeking” schema, which he acquired because he only got attention as a child when he “performed.” When triggered, this schema shifted him into an “Approval-seeker” mode of behavior in which he tried too hard to impress people in authority. About 31% of our leaders reported that this pattern of behavior was Mostly or Completely True for them. However, when the desire for recognition from Paul activated Daniel’s “Recognition-seeking “schema, he shifted into an “Approval-seeker” mode.

Our research revealed that most executives have one or more early maladaptive schemas and corresponding dysfunctional modes of leader behavior. This does not mean, however, that all leaders need therapy. It may help those whose schemas run deep and whose modes are highly damaging and difficult to control. We have had some tremendous successes working together as therapist and coach with the same clients.

However, for most leaders, it’s enough to work with an executive coach who is versed in Schema Theory and can help them understand and manage their dysfunctional modes. This starts with an assessment done by a coach who understands the framework and employs supporting diagnostic tools. Once identified, the focus of the coaching is not on healing the underlying schemas; that is the work of therapists with in-depth training. Coaches focus on helping the client to (1) understand when and how dysfunctional leadership modes get triggered and (2) learn to anticipate, avoid, and mitigate their impact on one’s leadership.

For leaders like Paul, for example, who have a “Demanding Critic mode that is rooted in the “Unrelenting Standards” schema, the starting point is to recognize that the mode exists and explore how it impacts their leadership. When you are in the “Demanding Critic” mode, how do you feel, and what behaviors show up in your leadership? Once awareness is raised, the next step is to recognize how (and how often) the mode gets triggered. What circumstances lead to the mode shift from “Healthy Adult” to “Demanding Critic”? How often does it happen, and what are the implications when it does? Understanding the frequency and intensity in which this mode shows up offers important insight into the nature of the work to be done. If the mode shows up frequently and is intense and highly damaging, it’s a signal that in-depth therapeutic work should be explored.

Assuming this is not the case, however, and armed with insight into one’s dysfunctional leadership modes, the coaching work can proceed to anticipating and avoiding them. The coach works with the leader to help them build their awareness that a shift into a dysfunctional mode is in danger of occurring. This is a big step in its own right. While understanding one’s modes and recognize that they have been triggered after the fact, the mode shift still has occurred, and some damage has been done. It’s another big step to develop anticipatory awareness that a mode shift is about to happen and take preventive action.

Taking preventive action means developing strategies to avoid and mitigate the impact of mode shifts, such as diversion, disengagement, and delay. Diversion essentially means trying to change the subject. If there are topics or behaviors that one knows are likely to trigger a dysfunctional mode, one can try to shift the conversation or break the frame of what is happening. Failing this, disengagement can be a strategy worth trying. This can range from “I need to take a break” to “I can’t discuss this at all further right now.” Finally, when triggered, it can help to pause, breathe, and delay the resulting reaction. We believe, for example, they every leader should have a folder of “emails I wrote but didn’t send.”

Developing the ability to anticipate, avoid and mitigate one’s dysfunctional leadership model doesn’t heal the underlying schemas: the propensity to get triggered, shift into a dysfunctional mode and react in potentially damaging ways remains but becomes more manageable and less damaging.

For leaders who decide to go down the therapeutic, schema-healing road, with or without the support of a coaching partner, the benefits can be substantial. To do this, however, we have found they first have to overcome a significant barrier: the fear that doing this work will make them less effective as leaders. This is particularly the case for executives with the most common schema: “Unrelenting Standards.” Leaders with this schema believe that perfection is the key to success, even survival. So, it’s natural for them to feel that the alternative to achieving perfection is mediocrity and that ceasing to strive relentlessly for perfection will lead to failure.

The good news is that the executives with whom we have partnered have become more effective leaders, not just people who are more satisfied with their lives. The alternative to unrelenting standards is not no standards; it’s high-but-achievable standards. And the alternative to the pursuit of perfection is not mediocrity; it’s striving for excellence.

Professor of Leadership and Organizational Change at IMD

Michael D Watkins is Professor of Leadership and Organizational Change at IMD, and author of The First 90 Days, Master Your Next Move, Predictable Surprises, and 12 other books on leadership and negotiation. His book, The Six Disciplines of Strategic Thinking, explores how executives can learn to think strategically and lead their organizations into the future. A Thinkers 50-ranked management influencer and recognized expert in his field, his work features in HBR Guides and HBR’s 10 Must Reads on leadership, teams, strategic initiatives, and new managers. Over the past 20 years, he has used his First 90 Days® methodology to help leaders make successful transitions, both in his teaching at IMD, INSEAD, and Harvard Business School, where he gained his PhD in decision sciences, as well as through his private consultancy practice Genesis Advisers. At IMD, he directs the First 90 Days open program for leaders taking on challenging new roles and co-directs the Transition to Business Leadership (TBL) executive program for future enterprise leaders, as well as the Program for Executive Development.

Consulting psychotherapist, Director of the Schema Therapy Institute of NJ-NYC

Wendy Behary is a consulting psychotherapist, Director of the Schema Therapy Institute of NJ-NYC, and author of Disarming the Narcissist. Michael Watkins is a Professor of Leadership and Change at IMD, Co-Founder of Genesis Advisers, and author of The First 90 Days.

July 8, 2025 • by Alyson Meister, Marc Maurer in Leadership

Marc Maurer shares how ON grew from startup to IPO by defying hype, focusing on purpose, and leading with humility in this candid Leaders Unplugged episode....

July 7, 2025 • by Richard Baldwin in Leadership

The mid-year economic outlook: How to read the first two quarters of Trump...

July 4, 2025 • by Arturo Pasquel in Leadership

Susanne Hundsbæk-Pedersen, Global Head of Pharma Technical Operations at Roche, shares how she has navigated the various pivots in her career, and the importance of curiosity, optimism and energy. ...

July 3, 2025 • by Eric Quintane in Leadership

Entrepreneurial talent who work with other teams often run into trouble with their managers. Here are ways to get the most out of your ‘boundary spanners’...

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience