Why being alert is not enough to beat VUCA and disruption

What do you do if Amazon, Google, Uber or Airbnb are expanding into your company’s field? Or a new regulation changes the rules in your ecosystem, opening the door to new competition? The temptation to react as fast as possible in an unstructured way is high: anyway everything changes all the time! Tesla announced its “Semi” truck in November 2017 in typically flamboyant style. Let’s have a look at what disruptions Semi could cause. At first sight, this seems like it is only a competitor for truck manufacturers. Except that Elon Musk has proclaimed: “When three Tesla trucks travel in convoy, the total operating cost per mile beats rail.” Did the rail companies anticipate Tesla entering their sector? Can they respond successfully in time? In this example, between the announcement and expected start of production, traditional transportation companies have about 24 months to react – very short notice for an industry of this scale.

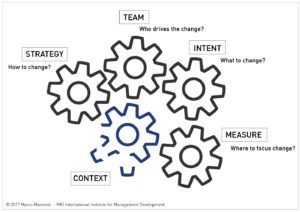

The “Integrated Alertness Model” is a disruption management framework that can help us better understand and address situations like this.

Developed by taking into account the aftermath of 100 change projects I have observed in various industries over the past 20 years, the model focuses on the five dimensions that typically go wrong during strategic implementation: failing to adequately spot and understand alterations in the context in which the company operates, failing to clearly define the intent behind the change required, failing to measure the right aspects during implementation, failing to draw up a suitable strategy, or failing to put the right team in charge.

Let’s assume hypothetically that the new Tesla trucks will significantly reduce the amount of goods transported via rail. In this case, rail cargo companies facing disruption should ask these five questions before reacting to Tesla’s encroachment on their territory:How bad is the disruption and why?

The Tesla disruption breaks the context gear, and before debating what to do, it is crucial to understand what the consequences are. Does the disruption threaten to end the company? How much market share does the new entrant endanger? Will the effect be temporary or definitive? What scenarios could become reality? Has the incumbent company been complacent and arrogant for too long? All these questions will help define what to do next.

What to change?

There are basically two types of change: One focuses on repairing the gear (i.e. the effect of the disruption), and the other looks at redefining the entire ecosystem, meaning that the company transforms so extensively that it becomes a completely different player. Right now, we see a lot of “trying to repair” with Uber, for example; taxi companies are putting pressure on governments for legislative barriers in order to block the entry of the competitor. Up against Tesla, an example of a rail cargo company trying to repair the context gear could simply be correcting its value proposition in order to raise the competition bar higher.

Where to change?

Answering this question is about defining the focus of change through carefully chosen measures. Then during execution, the decisions made in this step will be used to track progress. These indicators also provide guidance when things start becoming complex or ambiguous: “When in doubt, look at the measures!” Typically if a rail cargo company decided to take the defensive approach mentioned above, then the indicators are likely to be focused on cost optimization, reliability, point to point speed, sales, market share, client satisfaction, and the like.

In general, companies facing disruption absolutely must get the “what to change” and “where to change” right. In their November-December 2017 Harvard Business Review article, IMD’s N. Anand and Jean-Louis Barsoux state: “Often organizations pursue the wrong changes – especially in complex and fast-changing environments, where decisions about what to transform in order to remain competitive can be hasty or misguided.”

How to change?

This question centers on strategy. Often, the problem with strategy is that it is more dogmatic than realistic. In practice, the best strategy is the one your organization can execute. When designing a change strategy, it is crucial to face reality and take into account elements such as company culture, the strengths and weaknesses of the organization, any other current dynamics at play, and threats to the business. In other words, the strategy needs to incorporate both the external and internal environments. The approach to change is not one-size-fits-all; a traditional, essentially local company will not engage in change (whatever the extent) in the same way as a multinational tech company, for example.

Who drives the change?

This is the last, but certainly not the least, element in the process. Making change happen is very much about leadership, and thus the “right people” need to be put in charge. How often do we see strategic teams composed of “whoever’s available”? As mentioned in a previous article, team readiness can be measured using the criteria in the “PIKES” framework: alignment on purpose, perfect integration, specific knowledge, in-depth understanding of the ecosystem, and keen self-awareness.

A turbulent context is by its very nature unpredictable, so disruption can hit when a strategic change project is already under way; the context gear can break several times! In the rail cargo example, the initial break was due to Tesla’s Semi, but as companies work to meet the challenge, they could be blindsided by other events. Switzerland, for example, has stringent laws on trucks – their size and the time they are allowed to operate are limited. What if the Swiss authorities suddenly granted permission for larger trucks to cross the country and to travel at night?

How bad would that additional disruption be? Would the defensive approach still be the most appropriate, rather than a more radical route? If drastic change is required, the company will also have to reconsider the what, where, how and who. But this is still not enough: After setting the new intent and adjusting all the other elements, it needs to go one step further to embed alertness throughout the system. Remaining vigilant about gauging the morale of the core transformation team allows you to anticipate serious issues. Keeping an eye on how your change is progressing against your chosen measures allows you to assess the adequacy of your strategy. An implementation plan that keeps missing its milestones is surely the symptom of another problem in the system.

In other words, not only can the context gear break several times but the other gears can also break, and each tells a different story.

Why is this critical? Because as the example of Tesla’s Semi shows (provided Tesla has enough cash to achieve its promise), disruptions nowadays do not leave a lot of time for reaction. So it can be even more damaging if a company wastes energy working on the wrong changes or screws up the execution.

On the positive side, there is also a huge opportunity. When companies succeed in global transformations, they make the disruption that caused their context gear to break irrelevant. And there’s more: These companies with integrated alertness could well become immune to further context changes or… they might become disruptors themselves!

Marco Mancesti is R&D Director at IMD and an alumnus of the High Performance Leadership (HPL), the Advanced High Performance Leadership (AHPL), Orchestrating Winning Performance (OWP),Organizational Learning In Action (OLA) and Breakthrough Program for Senior Executives programs.

He has published several articles on the concept of VUCA and disruption, amongst which:

Why VUCA business leaders end-up paralyzed, blind and deaf?

Do you have the right implementation team?

Is VUCA the end of strategy and leadership?

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Last week, a notification flashed. “Add your email address for extra security,” my phone chirped. It was from WhatsApp. I stared at the screen, a single question forming in my mind: Security? Or surveillance? I tapped “No.” The feeling wasn’t ange...

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

in I by IMD

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Published by International Institute for Management Development ©2025

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

in I by IMD

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications