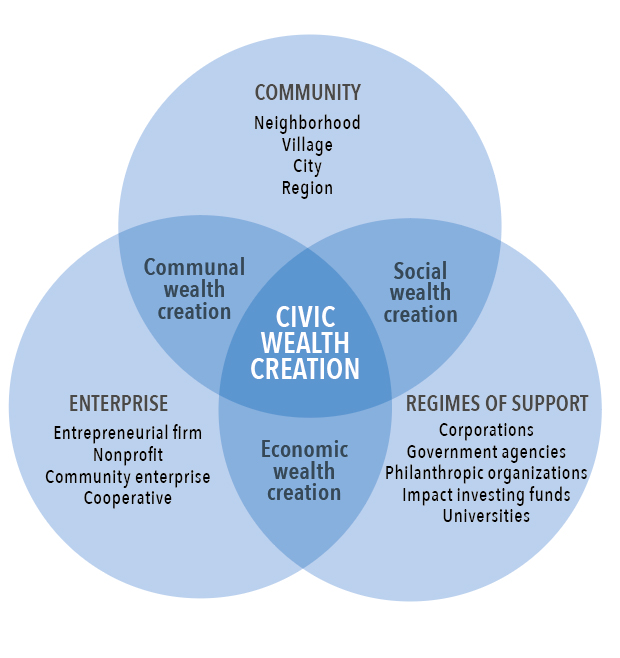

Social wealth is created when regimes of support directly assist and collaborate with a local community. They can provide business experience (corporations), administrative support (non-profits), funding and advice (philanthropic organizations), knowledge (universities), and more. Social wealth reflects the benefits accruing to the well-being of a community that embraces the contributions of its supporters, such as improved access to healthcare, education, and justice, among others. For example, Bush Brothers & Co, the leading provider of baked beans in the US, led the effort to convert an old school building into a primary healthcare clinic serving the rural community of eastern Tennessee where most of its employees live. The company wanted to provide better access to healthcare for its employees and their families as well as for the residents of the surrounding area, who had to travel long distances to see a doctor or a dentist. The company also wanted to preserve a local historic building, which was built in 1925 and had been vacant for years. The company, with strong connections to the school as many of its employees and their relatives had attended it, wanted to honor its legacy as a center of education and community for generations. Finally, as any sound business caring about its viability would do, Bush Brothers also wanted to reduce its healthcare costs, which were rising due to the lack of preventive care and chronic conditions among its workforce.

Communal wealth is created out of a community’s own entrepreneurial efforts to enhance its lot with limited influence from the regimes of support. It manifests as capacity building, enriched culture, and enhanced self-sufficiency. Consider the Brixton Pound, a local currency launched in 2009 by activists who wanted to support the local economy in the London borough of Brixton and promote social justice. The Brixton Pound can only be spent at participating local businesses, which encourages people to shop locally and keep money within the community. It’s an example of how communities use creative problem-solving – in this case, a unique local money system – to highlight their values and boost their communal prosperity.

It is important to note that the model presented in the graphic is dynamic: civic wealth can also be created in moderate forms when one stakeholder group is less engaged than the other two. For instance, a non-profit that combines community leadership with corporate donations and volunteers to build local infrastructure and enhance local well-being generates both communal and social wealth. The community developing an entrepreneurial spirit and a sense of responsibility contributes to the creation of communal wealth. The community also benefits from the creation of social wealth through enhanced facilities, leading to various advantages such as a healthier and more active population. However, such an initiative does little to create economic self-sufficiency and thus would have a limited impact on economic wealth, resulting in a moderate level of civic wealth creation.

The five principles of civic wealth creation

Five clear principles indicate that CWC is strengthening communities through commerce and collaboration. Taken together these principles are what distinguishes CWC from other forms of social helping such as philanthropy, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and social work.

1. Shared purpose

Stakeholders are engaged in community life, have a sense of responsibility for others, and contribute in ways that bring about positive change. This principle more than any other explains why we use the term “civic” to characterize the phenomenon: it emphasizes the importance of involving local people, and of caring for others beyond just economic matters.

Example: There are few better examples of this than Mondragon, a federation of worker cooperatives that began in Spain’s Basque region in the wake of two wars. It was a desperate time for workers and their families, but through thoughtful collaboration and the determination to focus on both fairness and practicality, they were able to develop very forward-thinking practices. Today, cooperative members, who ascribe to four core principles – cooperation, participation, social responsibility, and innovation – work directly alongside each other to develop and support the civic wealth of the region. Their purpose stems from mutual involvement in both work and community life, which helps build a sense of solidarity and collegiality.

2. Prosperity

Many of the problems that communities face cannot be solved with simple fixes or one-dimensional solutions. For systemic change to take place, a wide array of resources – including physical, cultural, intellectual, political, financial, and natural resources – needs to be mobilized and organized.

Example: Fogo Island is a small island off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, that has faced many challenges, such as the decline of the fishing industry, the out-migration of youth, and the loss of cultural identity. However, the community has mobilized a broad array of assets and partners to support its change efforts and revitalize its economy. In particular, a native who became a Silicon Valley executive helped position Fogo Island as a tourist destination. These efforts not only brought residents back but also boosted economic prosperity and strengthened community resilience in the face of future shocks.

Audio available