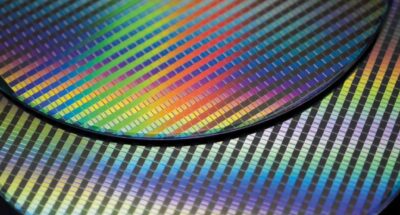

Europe needs Chips Act 2.0 to compete in digital race

Former French finance minister Bruno Le Maire says Europe needs to act urgently to secure its supply of semiconductors or face relegation to the global slow lane. ...

Audio available

by Anand Narasimhan Published June 27, 2023 in Audio articles • 13 min read •

For one thing, picking the 63-year-old Indian-born executive broke with a long-standing tradition that each World Bank chief comes from the US.

Some doubted the suitability of someone who’d had a mostly corporate and Wall Street career for a job running the world’s most powerful development finance institution. Banga launched fast-food franchises in India for Pizza Hut and KFC before going on to have a 13-year career at Citigroup.

Yet Banga has long been clear that his Indian origins and the experience he has gained from his background influences make him uniquely qualified for his various leadership roles.

In a 2020 interview with CNBC, he described himself as a “Made in India Guy”. Banga was born in Delhi and obtained his degrees from St Stephen’s College and the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. He cited his Indian background as highly relevant to working in emerging markets – where much of the World Bank’s work is done. “I grew up in India. I lived there. I worked there for the first 14 years of my [corporate] life,” the Financial Times quoted him as saying.

Banga’s descriptions of himself and his background and experience illustrate a phenomenon that has been building quietly but steadily for the past decade or so: the rise of the Indian-origin CEO.

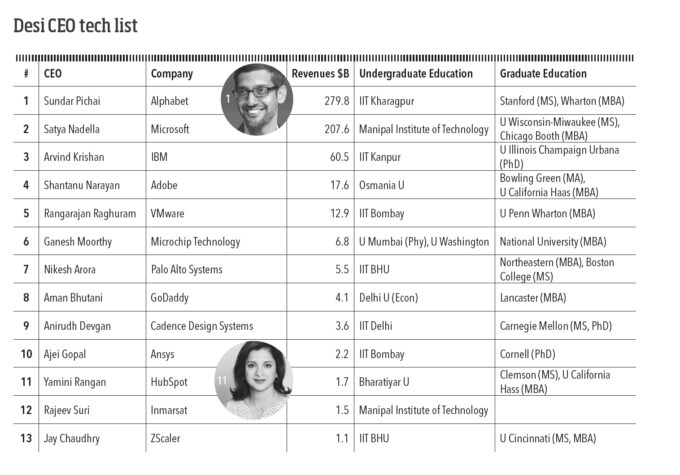

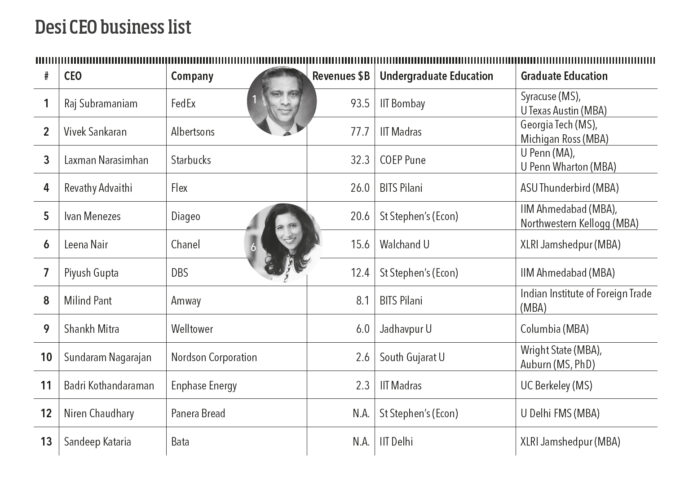

Our research has identified 26 chief executives of Indian origin globally, running businesses in a wide range of sectors from finance to IT and consumer goods (see sidebar). We have divided this into two lists, one of them a pipeline of CEOs focused on tech, and another on business in general.

Together, the lists include some of the arguably best-known names – Sundar Pichai of Alphabet (parent of Google), Leena Nair of Chanel, Satya Nadella of Microsoft – and some perhaps less well-known figures including Badri Kothandaraman of Enphase Energy and Vivek Sankaran of the US retailer Albertsons. We are calling them “Desi CEOs”, after the word that Indians use self-referentially.

“ When playing football, the driver’s kid would be playing, and the rich tycoon’s kid would be playing, too. So having to get used to diversity is a tremendous source of strength.”Piyush Gupta

The reasons for the emergence of this new breed of global CEO may not be immediately obvious. To be sure, many of these Desi CEOs came of age in the 1990s – a time of great transformation in India as the country left behind decades of socialism-inspired central planning to embrace market reform that created new social and economic conditions. In this new India, graduates could contemplate the possibilities of a career in a global corporation rather than the traditional safe havens of the Indian civil service or public sector companies.

Yet why would one country, albeit one as populous as India, account for such a significant presence in the global C-suite? And why now?

To gain answers and insights, I spoke with two Desi CEOs who are currently in post: Piyush Gupta, who runs DBS, Southeast Asia’s largest bank; and Sandeep Kataria, CEO of Bata, the footwear manufacturer headquartered in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Gupta spent 27 years at Citibank, before taking on the top job at DBS in Singapore in 2009, while Kataria had a 17-year career at Unilever before working in senior roles at Yum! Brands, Pizza Hut, and UK telecoms group Vodafone. Kataria ran Bata’s India business for three years before becoming global CEO in 2020.

Interestingly, both leaders cited some of the same factors, when asked what was behind the phenomenon which, collectively, can be considered the “push factors” behind the rise of the Desi CEO.

The first is India’s education system, specifically its use of English – the dominant language in business globally. “This community is not just English speaking but English thinking, many of them,” Gupta said. “And so, facility with the English language makes them globally transportable.”

Kataria explained: “My parents had migrated from Pakistan pretty much with the stuff that was on their backs. What I heard from them always was: ‘You’d better study, or you’ll have to be a taxi driver.’

“With our education [system] we’ve been lucky. We may beat up the rote learning system, but there is a discipline that it teaches you. If you have to get through to the top education establishments and on to big companies like Unilever, you need to have a work ethic and a need to assimilate and learn. It stands you in good stead.”

“ The ethnicities, skin color, and language that you grow up with, but also the backgrounds, do prepare you to be more open to diversity. ”Sandeep Kataria

Gupta pointed out a feature of India’s education system that has the result of making students highly motivated to get ahead – what he called its narrowness: “In any big city, there are 10 high schools that are really high quality. Multiply that by 10 cities and you are talking about 100 schools, and then multiply that by 200 people in a class, that’s 20,000 people coming through the system. It’s not a large footprint. The system is also brutally competitive.

“There are two subtexts to this: one, the people who make it are probably the best of the best. The other thing is that the system’s narrowness hones the competitive instinct.”

A second characteristic relates to diversity, specifically a natural ability to manage a diverse workplace thanks to an Indian upbringing. Banga put it simply in a 2010 interview with the FT: “When you come to the US and hear people talking about diversity, well, I grew up with it.”

Gupta broke it down for me from his own experience, recalling that he went to a convent school, which involved attending prayers at the local cathedral in the morning.

“People tend to think of Indians as being more or less the same, but India is very diverse – by religion, by background and culture, by socio-economic status,” Gupta continued. “When playing football, the driver’s kid would be playing, and the rich tycoon’s kid would be playing, too. So having to get used to the diversity is a tremendous source of strength; it builds adaptability as well as helps with people management skills.”

Kataria had a similar view. “The ethnicities, skin color, and language that you grow up with, but also the backgrounds, do prepare you to be more open to diversity.”

He believed that this inculcated a sense of openness to travel and adjusting to different living conditions, “which not all nationalities are open to”.

For Gupta, this willingness to be adaptable has helped him in his current role as CEO of what was a quintessentially Singaporean bank — it was founded as Singapore’s development bank in 1968. Under his leadership, DBS transformed from a “sleepy bank” to one that spans 19 markets and is well known to be at the forefront of leveraging digital technology to shape the future of banking.

“The fact that I came from a diverse kind of background and dealt with different kinds of people allows me to be able to manage very different cultural nuances across the region,” Gupta said. “I found this when I went to Indonesia. It’s a very different culture; you cannot be direct. They tend not to say ‘no’ directly. For example, if you ask a 90-year-old guy if he’s married, he won’t say ‘no’, he will say ‘not yet’.”

Organizations must become more inclusive and diverse to thrive in the future: the business case is as compelling as the moral imperative. How can executives foster inclusion to unlock the power of diversity, while recognizing and tackling inequity and discrimination? In the June issue of I by IMD, we explore how leaders can build organizations and design products and services that are truly inclusive.

A third characteristic is an analytical mindset combined with soft people skills.

It is typical for the global Desi CEOs to have their thinking shaped by an undergraduate degree in engineering or another quantitative field such as economics. “It is a very analytical way of approaching things,” Kataria observed. “If you lay out the facts and the processes, you will be able to reach the right answer. You were able to approach almost everything by saying, “OK, let’s just get to the real brass tacks and we will find a way out. There is a solution.” It’s very scientific and you will be able to get there.

“The other thing that it did teach you was that even though you managed to get admitted to a great engineering school, there were really smart people around you. You were never allowed to have a chip on your shoulder. So it kept you humble and always open to learning.”

Kataria acknowledged picking up interpersonal skills at business school. “You realize that it was not the smartest kid in class who was doing the best, but the person who could work with other people,” he said.

Gupta believes that Indian culture’s roots in family and community tend to instill the value of working together. “Even though I learned Western human resource practices, having formal KPI systems, goal setting, and coaching and so forth, my instinct is to put my arm around somebody and to manage through personal connection and community,” Gupta said of his style of leadership. “I think it creates a gentler kind of leadership.”

It’s not surprising therefore to see “alpha male” corporate leaders being replaced by the gentler presence of Desi CEOs such as Satya Nadella and Sundar Pichai.

The fourth characteristic is what Gupta calls “learning to make the elephant dance”: how an Indian background helps when it comes to dealing with business complexity.

Kataria credits Hindustan Unilever for pushing its graduate management trainees to take responsibility for managing complex businesses very early in their careers: “If you were an area sales manager, you were expected to be the person who knew that area the best in the company. And early on take big decisions which impacted the revenue significantly. But also, very large teams in the field. I counted once – there were 1,800 people whose livelihoods depended on the decisions I made.”

“Most emerging markets – and India is a good example – are very complex,” said Gupta. “The system doesn’t work as smoothly. And so you’re trained in India from a very early age to try and make the system work for you. You’ve got to learn how to make an elephant dance, and that ability to do so is actually very useful in any situation.

“So, from a personal development standpoint, having an Indian background actually teaches you how to make these cumbersome systems work.”

While these characteristics of Desi CEOs help to explain their rise, it’s also important to understand the environment into which such leaders are being propelled: the pull factor, if you will.

Gupta’s take on this was that, as late as the 1980s, there were only two or three global organizations where you would expect to see Indians break the “glass ceiling”, as he called it, citing Unilever and Citibank as among the first companies to start hiring Indians from Indian business schools as future corporate leaders.

Then India started liberalizing and, in the 1990s, investment banks and consulting firms as well as multinationals started sourcing talent out of India.

Finally, as Gupta pointed out, the world’s big banks have been shifting their approach. Citibank named Vikram Pandit CEO in 2007 and Deutsche Bank appointed Anshu Jain in 2012, signposting the elevation of Desi CEOs on the global financial stage.

“Until relatively recently, it would have been unimaginable to think of [a Desi CEO] in the [banking] industry,” Gupta said, citing the influence of diversity, equality, and inclusion policies and thinking as playing a key role. “So, I think it was a conscious shift in global companies to really focus and not make this [DE&I] a ‘check-the-box’ exercise. I think people started to get a lot more open to looking for diverse ethnicities in their management ranks.”

So, what does the future hold for the Desi CEO? I believe the number of tech-focused CEOs in what we are calling the “Desi Tech CEO pipeline” will continue to climb at a steady rate due to sheer momentum. There is an installed base of talented Indian-origin professionals working in tech companies in the US who will continue to find their way to the top.

As India’s startup ecosystem becomes more sophisticated, the tech talent that would have migrated to the US will stay put. Over the next decade, a handful of unicorns with a homegrown startup CEO will break out to create a world-dominating business model relying on an international workforce. This breed of Indian leaders will join the bracket of Desi CEOs atop India’s largest tech companies: Rajesh Gopinathan (Tata Consultancy Services), Salil Parekh (Infosys), C Vijayakumar (HCL Tech), Ravi Kumar S (Cognizant), and CP Gurnani (Tech Mahindra).

There is even more potential in the pipeline of “Desi Business CEOs”, which could explode. For many multinationals, India is quite simply their biggest market by value and volume in Asia. Regional heads, such as Deepak Iyer at confectionary company Mondelēz and Vismay Sharma at L’Oréal, already handle businesses bigger in revenue terms than some of the businesses run by Desi CEOs on the list. It’s worth noting that the market capitalization of Hindustan Unilever amounts to at least two-thirds that of Unilever worldwide on any given day.

Finally, let us return to elephants, and especially to an elephant in the room: the numerical dominance of Desi male CEOs. Will we see a third Desi CEO pipeline, that of female Indian origin CEOs, following in the wake of Indra Nooyi (PepsiCo), Leena Nair (Chanel), Yamini Rangan (HubSpot), and Revathy Advaithi (Flex)? Only then can we truly talk about the importance of diversity in the story of the Desi CEO.

I by IMD has identified 26 CEOs of Indian origin that we are calling “Desi CEOs” – the Hindi word “desi” refers to all things Indian. They are divided into two lists, or pipelines: Desi Tech and Desi Business.

To qualify, an India-born CEO must have completed their undergraduate degree at an Indian institution. The bachelor’s degree is a pivotal rite of passage – there’s the anxiety of leaving home and the exhilaration of being free of parental shackles. As Piyush Gupta and Sandeep Kataria have noted, students who gain admittance to an elite program feel the pride of making it against the odds – and face the realization that there are people smarter than them in the room.

Of the 26, 22 Desi CEOs have an undergraduate engineering degree, while 19 of them followed up with a post-graduate business degree – 16 from the US or UK, and five from an Indian institution.

The Desi Tech pipeline comprises those who made a mark early in their careers with their deep technical expertise. Many have a master’s degree, and three have a PhD. As they graduated and joined the workforce, they found support and mentoring in the critical mass of Desi technology professionals already well-established in the US, and Silicon Valley in particular. In addition to their formidable technical chops, the soft skills acquired growing up in India allowed them to break the glass ceiling and become credible candidates in the CEO succession process. Yamini Rangan of HubSpot stands out as the sole woman on this list.

This pipeline includes many CEOs who cut their teeth working in businesses in India, such as Leena Nair at Chanel and Sandeep Kataria at Bata, both of whom had long spells in India’s “CEO factory” of Hindustan Unilever – honing their functional skills in human resource management and marketing respectively as they climbed the ranks. Yum! Brands, a company that Ajay Banga worked for, is another CEO incubator, counting Kataria, Niren Chaudhury and Milind Pant among its alumni.

As with DBS’s Piyush Gupta, wider experience in Asia was part of the pathway to the CEO’s office for Raj Subramaniam, who served Fedex in Hong Kong for seven years in a marketing role, and for Rajeev Suri, who covered Asia-Pacific for Nokia. Laxman Narasimhan and Vivek Sankaran had a more conventional route, both starting their careers as consultants with McKinsey and serving in senior roles at PepsiCo.

Anand Narasimhan serves as Shell Professor of Leadership and Governance at IMD. He is also Director of the Team Dynamics Training for Boards program. He is an expert in leadership development for senior executive teams and boards, and his research focuses on institutional change, organization design, social networks, and emotions in the workplace.

July 10, 2025 • by Bruno Le Maire in Magazine

Former French finance minister Bruno Le Maire says Europe needs to act urgently to secure its supply of semiconductors or face relegation to the global slow lane. ...

Audio available

Audio available

July 8, 2025 • by Mike Rosenberg in Magazine

A new framework encourages leaders to see the world as PLUTO – polarized, liquid, unilateral, tense, and omnirelational. It’s time to think differently and embrace stakeholder capitalism....

Audio available

Audio available

July 3, 2025 • by Eric Quintane in Magazine

Entrepreneurial talent who work with other teams often run into trouble with their managers. Here are ways to get the most out of your ‘boundary spanners’...

Audio available

Audio available

June 26, 2025 • by Michael Yaziji in Magazine

Forward-thinking leaders proactively shape their external environment, turn uncertainty into certainty, and create substantial value in the process....

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience