Why leaders should learn to value the boundary spanners

Entrepreneurial talent who work with other teams often run into trouble with their managers. Here are ways to get the most out of your ‘boundary spanners’...

Audio available

by Vanessa M. Patrick , Candice R. Hollenbeck Published July 26, 2023 in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion • 10 min read •

The global cosmetics industry is a $500 billion market that dates back to the early 20th century. In 2017, international pop star Rihanna launched Fenty Beauty – a range of cosmetics with over 40 shades, designed to suit any skin tone. The brand scored $100 million in sales in the first 40 days. Time magazine named Fenty Beauty one of the best inventions of 2017 stating: “Fenty’s unabashed celebration of inclusivity in their makeup campaigns put an unprecedented spotlight on the need for diverse beauty products.”

By simply widening the lens and recognizing the diversity of skin tones in the marketplace, Fenty Beauty hit the jackpot. Today, all businesses have the opportunity –and the responsibility– to embrace inclusivity at scale through the design of products and services that enable accessibility in new and meaningful ways to benefit a diverse customer base.

Not doing so could come at a cost. According to Harvard Business Review Analytics, consumers are becoming more vocal and active when it comes to inclusion: 64% of consumers surveyed are taking action to support brands that recognize their uniqueness. At the same time, in a highly politicized and scrutinized marketplace, inclusive design can help firms mitigate against reputational risk, such as accusations of “diversity washing” or being faced with lawsuits for discriminating against underserved groups due to inaccessible products or services.

To make design processes more inclusive, companies must integrate the expectations and needs of all consumers, not just their traditional customer base or the largest demographic cohort in any given market. Many organizations struggle to make meaningful progress here, in part because there is little concrete guidance available to advise managers on how to implement the necessary granular, systemic changes.

Our research paper, Designing for All: Consumer Response to Inclusive Design, showed that inclusive design requires companies to recognize and understand the needs of “edge consumers” who are often overlooked or even invisible in the marketplace. They can then build design approaches that deliver more inclusive products, services, technology, and experiences. Based on our research, we offer a set of frameworks that help managers develop and promote an inclusive design mindset.

First, a designer should understand which groups might have been excluded from the design process and have a structured way to consider their needs. Although segmentation and target audiences are common marketing practices, this has tended towards prompting the description of an “average” consumer or a “representative customer persona”. It can be easy or tempting for companies to simplify things and categorize consumers as one-dimensional by relying on their most visible characteristics, but this inclination can result in products excluding some consumer groups, which may incur reputational risks and lost opportunities.

We looked at a broad array of literature from disciplines as diverse as psychology and mental health to architecture and education to learn how other professions addressed this challenge and to establish a best practice approach for design purposes.

We settled upon the “ADDRESSING” framework developed by clinical psychologist Pamela Hays that calls attention to previously neglected groups in a clear and simple way. This acronym-based framework offers a range of identity markers to be mindful of when designing for inclusion. Importantly, it allows designers to consider more than one aspect of identity. After all, identity is intersectional and can include any combination of age, developmental and acquired disabilities, religion, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, indigenous heritage, national origin, and gender.

By applying the ADDRESSING framework, designers have a clear guide to envision the needs and expectations of diverse consumers – it serves as a continual reminder that there is no “average” consumer. When managers recognize the complexities of human experience and identity, they are more likely to deliver products that serve all possible users.

Whether a company’s products and services are inclusive or not makes a significant difference to the way its brand is perceived in the marketplace. In the words of management theory pioneer Peter Drucker: “The purpose of business is to create and keep a customer.” Positive consumer emotional responses are critical for the enduring success of brands. Our research shows that, unsurprisingly, exclusion elicits negative emotional responses towards brands from consumers.

To understand how consumer responses to inclusion or exclusion manifest, our research offers a DARE framework (Design, Appraisal, Response, Experience) that draws on appraisal theory (a psychological theory that suggests that thoughts drive emotions – people evaluate or appraise a stimulus (objects and experiences) which then shapes their emotional responses to that stimulus) to underscore that exclusion is a personal and emotional experience.

We propose that, in the first instance, the design of products, services, platforms and experiences can signal different levels of social inclusion or exclusion. Secondly, consumers pick up on these inclusion and exclusion cues and appraise and evaluate designs based on their perceived level of inclusion. This appraisal process might involve questions like: Can I use this product? Was this product designed keeping my unique identity in mind? Third, these kinds of appraisals indicate the degree of mismatch between the individual and the design, which activates an emotional response from the consumer. These responses can range from “brand positive” happiness and admiration, resulting from inclusion, to “brand negative” anger and frustration as a result of exclusion. Finally, these emotions, in turn, shape consumers’ experience with the brand. Seeing the consumer journey through the DARE lens, managers look beyond just solving design problems to creating optimal, inclusive experiences for all consumers.

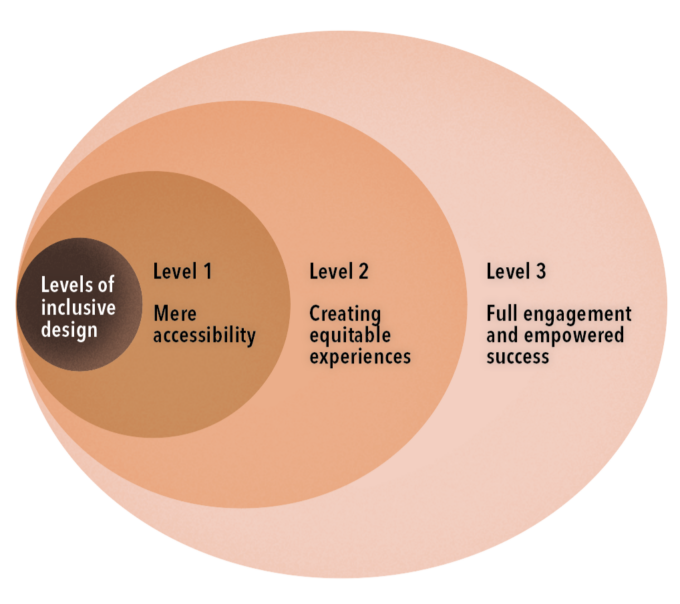

The next step in the journey is for companies to assess where they stand in terms of the inclusivity of their products and services (current position) and where they want to go (desired position). To help audit their marketplace offerings, we have devised a range of inclusive design levels from mere accessibility (Level 1) to creating equitable experiences (Level 2) to full engagement and empowerment (Level 3).

Level 1 design is focused on meeting minimum legal requirements or standards in order to remove barriers that prevent accessibility. Numerous examples exist of such efforts to be inclusive that merely address accessibility but nevertheless allow firms to check the inclusivity box. Let’s take the move by Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) to create a separate assistive website for people with disabilities rather than designing an inclusive website. For many wheelchair users, the experience of traveling by plane is stressful, painful, and often embarrassing. It is likely that being directed to a separate website evoked similar negative feelings. In recognition of this, the US Department of Transportation fined SAS $200,000 in accordance with the Air Carrier Accessibility Act. When businesses take shortcuts to inclusivity, even the simplest plans can go awry. Ogilvy, the British advertising company, launched a campaign for Cadbury’s new chocolate bar blending milk and white chocolate that purportedly promoted racial unity. Unsurprisingly, Cadbury’s efforts were viewed as trivializing an important issue.

Level 2 design takes additional steps to include previously overlooked consumers to reflect the diversity we see in everyday life. Level 2 design aims for equality by offering a range of products and services. Most video games, for instance, feature white, male characters – a move largely driven by the demographics of the target market. However, such narrow targeting excludes potential users and, for this reason, video gaming companies, such as BioWare, are increasingly adding more options, such as new female and LGBTQ+ protagonists. By “seeing” consumers who were unseen, Level 2 design offers these consumers the opportunity to equitably participate in the marketplace, such as IKEA’s “ThisAbles” line of free 3D-printed attachments that increase the usability of products for people with disabilities.

Level 3 design is the gold standard for inclusivity and allows fully equitable engagement and optimal consumer experience. With Level 3 designs, consumers enjoy what we refer to as “flow” because the “match” between the user and the environment fosters deep enjoyment and involvement with the related task; users can operate in and engage with their environment in a fluid and creative manner. While mismatches create disruptions, inconveniences, and embarrassments, matches create engagement, autonomy, and fulfillment. Level 3 design does not just offer rewarding benefits for consumers, but for companies as well. For instance, the FlyEase sneaker by Nike was designed in response to a letter from Matthew Walzer, a college-bound teenager with cerebral palsy. Walzer explained that he had “trouble tying laces and slipping into shoes without help” and wanted “sneakers that didn’t look like medical equipment”. Nike’s existing range of shoes was a mismatch for Walzer and the experience of wearing sneakers created feelings of embarrassment and frustration. In response, the company introduced its FlyEase range: fashionable, slip-on sneakers with a zipper that seals the back and easy-to-use Velcro-ties for the top – a design that offers flow for users by seamlessly integrating into their everyday experiences.

Organizations must become more inclusive and diverse to thrive in the future: the business case is as a compelling as the moral imperative. How can executives foster inclusion to unlock the power of diversity, while recognizing and tackling inequity and discrimination? In the June issue of I by IMD, we explore how leaders can build organizations and design products and services that are truly inclusive.

Numerous inventions that we all use today are the direct or indirect result of inclusive design: touchscreens, flexible straws, closed captioning, automatic doors, curb cuts, audiobooks, and speech-to-text software, to name a few. There is much evidence in industry and academic research that suggests inclusive design is good business practice and a stimulus for growth, while non-inclusive design represents a clear risk. Since the advent of the internet, consumers have a growing sense of power and a collective voice in terms of their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the products and services they use, and the associated brands. For businesses, the internet has provided a global reach, but with that comes a further imperative to understand and cater for consumer differences. Underrepresented consumers also offer an underutilized research tool. For instance, Microsoft included blind and visually impaired consumers to assist in creating the first toolkit with accessible data displays.

Technology firms (Microsoft, Google, Adobe, Salesforce.com) may be at the forefront of promoting inclusive designs, but other industries are also making inclusive design a priority. From fashion (Burberry) to toys (LEGO), gaming (Xbox Adaptive controller), consumer products (Herbal Essences shampoo) and furniture (IKEA), brands are responding to a societal push for change. Based on the success stories of a growing number of companies, inclusive design should now be an important consideration for all businesses striving to remain relevant, authentic, and competitive.

An example of addressing design exclusion from industry is kitchen, houseware and office supplies manufacturer OXO; the first company to understand that most kitchen tools exacerbated aches and pains for arthritic users.

Older adults with arthritis felt they were unable to cook without suffering the immediate consequences of pain. Consumers with arthritis also experienced the residual effects of non-inclusive design: the negative emotional consequences of using tools that impacted their ability to cook, such as not being able to prepare meals or provide for their families as they had done in past.

In response, and inspired by founder Sam Farber’s desire to help his wife handle ordinary kitchen tools, OXO used thermoplastic rubber, an innovative material at the time, to create products with better grip that were easier for arthritic consumers to use.

The problem Farber faced was how “to appeal to the broadest possible market, not just a very specific market of arthritis and the infirm”. Extensive user research allowed the company to create an innovative “Good Grips” design, which evoked positive emotional responses, not only for arthritic users but all users.

Today, the company is known for its non-slip “Good Grips” range and has experienced a compounded annual growth rate of over 30% since 1991. In addition, the company’s innovative designs have been featured in museum exhibitions, and despite having higher prices than competing brands, OXO is known to deliver higher sales even during a recession.

OXO has since expanded into other design areas such as office supplies, medical devices, and baby products.

Associate Dean for Research at the Bauer School of Business at the University of Houston

Vanessa Patrick is Associate Dean for Research, the Bauer Professor of Marketing, and lead faculty of the Executive Women in Leadership Program at the Bauer School of Business at the University of Houston. She has a PhD in business from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. She is author of The Power of Saying No: The New Science of How to Say No that Puts you in Charge of your Life.

Senior Lecturer of Marketing at the Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia

Candice Hollenbeck is a Senior Lecturer of Marketing at the Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia and her research explores the social and cultural dimensions of brand meaning and identity. She has published her work in the Journal of Consumer Psychology, Journal of Business Research, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Journal of Retailing, Consumption, Markets, & Culture, among others.

July 3, 2025 • by Eric Quintane in Audio articles

Entrepreneurial talent who work with other teams often run into trouble with their managers. Here are ways to get the most out of your ‘boundary spanners’...

Audio available

Audio available

June 24, 2025 • by Jerry Davis in Audio articles

The tech broligarchs have invested heavily in Donald Trump but are not getting the payback they bargained for. Do big business and the markets still shape US government policy, or is the...

Audio available

Audio available

June 19, 2025 • by David Bach, Richard Baldwin, Simon J. Evenett in Audio articles

As governments lock horns in our increasingly multipolar world, long-held assumptions are being upended. Forward-looking executives realize the next phase of globalization necessitates novel approaches....

Audio available

Audio available

June 2, 2025 • by George Kohlrieser in Audio articles

Leadership Honesty and courage: building on the cornerstones of trust by George Kohlrieser Published 17 April 2025 in Leadership • 5 min read DownloadSave Trust is the bedrock of effective leadership. It...

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience