How to harness the power of nonmarket strategy

Forward-thinking leaders proactively shape their external environment, turn uncertainty into certainty, and create substantial value in the process....

Audio available

by Jerry Davis Published September 30, 2023 in Finance • 9 min read •

Can businesses do well by doing good? Should they? This question has eluded resolution for generations and is now taken up by Republican presidential candidates in the US from Ron DeSantis to Mike Pence, who are campaigning against ESG investing and what they see as the sinister threat of “corporate wokeism”. One candidate, pharma investor Vivek Ramaswamy, has even published an anti-ESG screed titled Woke Inc. and launched a family of anti-ESG exchange -traded funds, evidently to prove that you can still do well by not doing good.

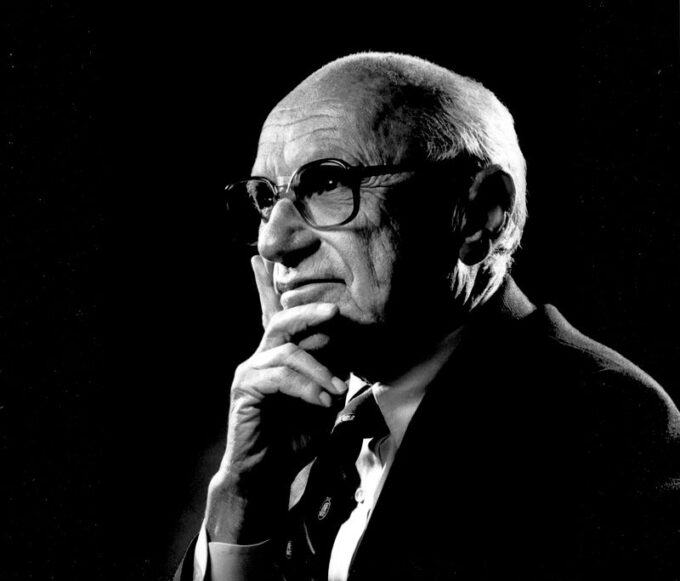

Opponents of ESG and those who decry corporate social responsibility almost inevitably harken back to an article published a half-century ago by Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman in the New York Times Sunday Magazine. The headline gives away the punchline: “A Friedman doctrine – The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” In the decades since it appeared, this short piece has become one of the most widely assigned articles in business schools, often paired with a reading on stakeholder capitalism on the obligatory ethics day.

As a piece of writing, it is a slippery work of sophistry full of hidden premises and hairpin turns. But its impact on the discourse cannot be denied, even as the world of business has been fundamentally transformed in ways that render its arguments in favor of unbridled capitalism and against corporate do-gooding sketchier.

Friedman’s argument runs as follows: only a person can have a responsibility, not “business”. Corporate executives, as people, are responsible to the corporation’s owners to make as much money for them as possible – executives are agents acting on behalf of the shareholder-principals who employ them, and shareholders love profits. If executives engage in do-gooding that reduces returns to shareholders (say, by cutting pollution more than is required by law), they are illegitimately imposing additional taxes on their employers and spending the income from those taxes at their own discretion. Taxing and spending are the functions of elected government, not unelected businesspeople, and allocating resources through politics rather than markets is socialism. Moreover, business executives have no particular expertise in pursuing goals beyond profit, and if they try their shareholders will probably fire them.

Do-gooding is permissible when it ultimately contributes to profits – say, supporting amenities in the community that make it easier to attract and retain talented employees, or to reduce pilferage and sabotage. But these actions are only justified if they contribute to the corporation’s self-interest.

The article closes with a flourish on the proper place of markets and politics in making societal choices. Markets involve voluntary cooperation for mutual benefit with unanimous consent. Politics requires conformity to decisions handed down by “a church, or a dictator, or a majority,” enforced by “the iron fist of government bureaucrats”. The choice for businesspeople was clear: maximize profits and avoid “social responsibility”, or be a hapless tool of socialism on the road to serfdom.

Friedman left out a couple of steps in his fevered dash. In particular, the moral case for maximizing profits may not be entirely intuitive, so here’s what he might have said. Profit represents the difference between what it costs to create a good or service and how much customers are willing to pay for it. If customers voluntarily buy something, they must value it at least as much as they paid for it (unless there was deception involved – and Friedman believes businesses shouldn’t deceive). Participants in the enterprise are all volunteers: workers, suppliers, and lenders agree to a fixed price for their contribution, and shareholders get whatever is left, that is, the profit. In this unanimous and voluntary cooperative venture, profit is both a motivator and a measure of the good that the venture has done for its voluntary customers. The greater the profit, the greater the social benefit. QED: business is off the hook for doing good if it does not yield a profit, because profit is good in itself.

The year 1970, when Friedman’s article was published, was arguably the high-water mark for “Big Business” in America. Unscathed by the Second World War, American industry had experienced astonishing growth and become an export powerhouse over the prior generation. Its biggest enterprises kept getting bigger: 25 corporations employed the equivalent of 10% of the US workforce. Big companies paid better than small firms and provided pathways for upward mobility for their career employees, growing a prosperous middle class. Moreover, in contrast to Europe, where governments provided healthcare and old-age income security for their citizens, these responsibilities fell to business. American corporations were like miniature welfare states, and it was no surprise that they were called on to exercise “social responsibility”. Many of them had annual revenues that surpassed all but the largest economies’ GDPs.

Consider the 10 biggest American corporations in 1970. Many were vertically integrated manufacturers operating large-scale facilities in the heartland. As Peter Drucker, one of the founders of modern management thinking, had pointed out a generation earlier, Ford’s River Rouge plant (where both my grandfathers worked as welders) was a microcosm of industrial society, employing tens of thousands of people for their entire adult lives in a massive and intricately coordinated enterprise. It is no wonder corporations came to be “imagined communities” on the same plane as states and were expected to be responsive to the popular will.

To create and sustain such an enterprise required collaboration among workers, suppliers, investors, and communities – a vast array of diverse interests all brought into harmony by market exchange, according to the Friedman dogma. To impose additional responsibilities on this fragile achievement was beyond the pale, and it was Friedman’s mission to put a stop to it.

And yet before the ink was dry on Friedman’s article, the “iron fist of government bureaucrats” was about to pummel Big Business into socially responsible submission – thanks to Richard Nixon.

Unlikely as it may have seemed, Nixon presided over one of the greatest expansions of corporate regulation in American history. In December 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency was launched to define and enforce environmental standards – taking specific aim at auto emissions and factory pollution. Later that month, Nixon signed the Occupational Safety and Health Act, creating another regulatory agency to make workplaces safer. The Consumer Product Safety Commission was launched in 1972 “to protect the American public from dangerous and deadly products”. And the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 gave the EEOC litigation authority to take on discriminatory employment practices in order to make the workplace more equitable for women and people of color. Big Business was suddenly drowning in requirements to meet environmental, social, and governance standards.

How does this square with the case against voluntary social responsibility? Friedman had stipulated at the start of his article that the business executive’s responsibility was “to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom”. But what if those laws started to feel too restrictive or costly for businesses in their socially responsible pursuit of optimizing profit for their shareholders? Friedman had made clear his disdain for having to conform to the will of a “church, or a dictator, or a majority”. By the end of the piece, his doctrine had lost an important constraint: “There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.” Abracadabra: law and ethical custom had dropped out of the equation and all that was left was the pursuit of profit without deception. As in a Dostoevsky novel, all is permitted. And business is awfully clever when it comes to navigating its way out of unwanted constraints.

No organization can escape the need to transform to become more sustainable. The need to act is urgent. It calls for strong leadership, difficult decisions, and deep cultural change. In Issue XI, we explore how to build sustainable organizations to succeed in turbulent times.

National laws may have seemed like a lamentable constraint when Friedman was writing, but over the subsequent years law became more of a choice for business. Corporations have grown skilled at optimizing where they incorporate, the nominal jurisdiction where their wares are sold, the legal home for their intellectual property, where they declare their profits, and where they source their labor (if anywhere).

For business, the law is simply an operating system, to be chosen the same way as accounting systems or server software. Delaware, Bermuda, Liberia – all are simply competing vendors courting their corporate customers. And as the vertically integrated behemoths of the past gave way to the “Nikefied” virtual enterprise of the present, the choices have exploded. As Financial Times commentator Martin Wolf memorably put it (with a nod to Stalin), today’s corporations are “rootless cosmopolitans”.

In my 2009 book Managed by the Markets, I described the all-American fashion brand Tommy Hilfiger: the company was “headquartered in Hong Kong, incorporated in the British Virgin Islands, held its annual meeting in Barbados, listed its shares on the New York Stock Exchange, and contracted manufacturing to vendors in Mexico and East Asia. (There is also a person named Tommy Hilfiger, who lives on Long Island.) Hilfiger is no more American than teenagers who wear Polo shirts, Hilfiger pants, and Timberland shoes are citizens of Ralph Lauren.”

Hilfiger is no more American than teenagers who wear Polo shirts, Hilfiger pants, and Timberland shoes are citizens of Ralph Lauren.

When Accenture went public in 2001, it was incorporated in Bermuda, where it joined a gaggle of crypto-American insurance companies. In 2009, proposed tax changes from the Obama administration encouraged the consultancy to re-incorporate in Ireland, where it was joined by Medtronic, Johnson Controls, and several pharmaceutical companies.

It is unclear how many of Accenture’s 721,000 employees consider Ireland home. Judging from the pharmaceutical and software profits booked in Ireland, it must be both the sickest and the most tech-savvy country on the planet.

Six of America’s biggest pharma companies recorded 90% of their profits overseas in 2022, despite the fact that the majority of their sales were in the US. And in 2020, a Microsoft subsidiary in Ireland reported profits of $315 billion – equal to three-quarters of Ireland’s GDP – despite the entity having no actual employees.

And then there is e-Estonia, a virtual jurisdiction where one can gain virtual citizenship for online businesses and draw on incorporation, banking, and payment systems – all without leaving the comfort of one’s laptop, wherever it happens to be.

It turns out that “law and custom” cannot slow down a company convinced of its duty to maximize profits. If you don’t like the law and custom where you are, it’s easy to relocate to a more congenial jurisdiction.

The biggest American businesses today bear little resemblance to the industrial giants that dominated the economy when Friedman wrote. Today’s enterprises are dispersed both geographically and organizationally. The 1970 cohort’s headquarters were concentrated in New York, Detroit, and Chicago – today’s group is scattered across the country. And while the Rouge plant employed 100,000 people, Apple’s retail stores average perhaps 100 staff each; a Walmart supercenter might have 350 workers, and an Amazon warehouse between 1,000 to 1,500. In contrast to the high wages and career-long employment of the 1970 group, retail work today is notable for its low pay and high turnover, with Amazon’s hourly workforce reportedly experiencing an astounding 150% annual turnover rate.

Today’s big enterprises are rarely the enveloping, community-defining institutions from Friedman’s time, and they retain only the faintest attachment to specific physical places (or tax or legal authorities). In fact, they defy attachment to any particular community to which they might owe some kind of social responsibility.

Perhaps Friedman won after all.

Professor of Business Administration and Professor of Sociology, University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business

Jerry Davis is the Gilbert and Ruth Whitaker Professor of Business Administration and Professor of Sociology at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business. He has published widely on management, sociology, and finance. His latest book is Taming Corporate Power in the 21st Century (Cambridge University Press, 2022), part of Cambridge Elements Series on Reinventing Capitalism.

June 26, 2025 • by Michael Yaziji in Magazine

Forward-thinking leaders proactively shape their external environment, turn uncertainty into certainty, and create substantial value in the process....

Audio available

Audio available

June 24, 2025 • by Jerry Davis in Magazine

The tech broligarchs have invested heavily in Donald Trump but are not getting the payback they bargained for. Do big business and the markets still shape US government policy, or is the...

Audio available

Audio available

June 19, 2025 • by David Bach, Richard Baldwin, Simon J. Evenett in Magazine

As governments lock horns in our increasingly multipolar world, long-held assumptions are being upended. Forward-looking executives realize the next phase of globalization necessitates novel approaches....

Audio available

Audio available

June 18, 2025 • by Michael Skapinker in Magazine

Polarization is a defining trend in the changing global order. Here’s how leaders can navigate the Trump-led pushback against diversity programs....

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience