Think back on your most painful learning experiences. Was the pain worth it? Have you really learnt as much as you could have from that experience?

In our working lives we encounter complexity, ambiguity, volatility and uncertainty on a daily basis. Our natural response is to attempt to bring structure, order, comfort and clarity to these situations. This is particularly true in leadership positions when others are counting on us. But these reflexes could be doing us a disservice – it is through experiencing discomfort that our insights and learning become the deepest. By exploring the personal challenges of leadership in today’s dynamic business context, we can build our capacity to read and respond to discomfort and complexity.

Dissonance parallels in music and leadership

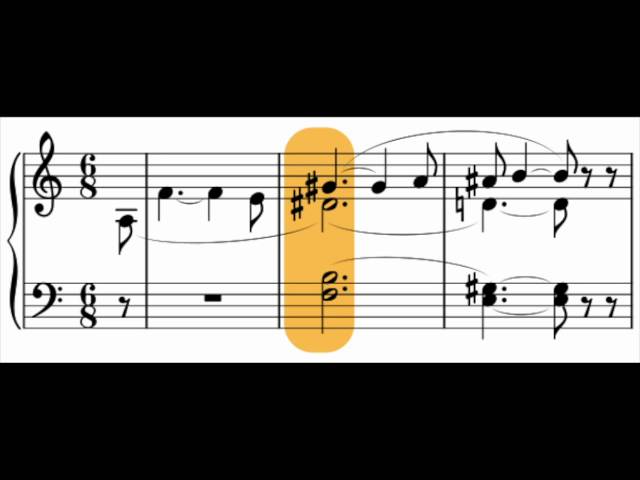

The challenges of leadership can be likened to music. An easy metaphor for our daily experiences, music – a communal, personal and visceral activity – elicits in us both comfort and discomfort. The discomfort we feel when listening to some music is called dissonance. Clear parallels can be observed between the evolution of dissonance in music and the development of our own capacity to learn through dissonance in our professional lives.

Consider how dissonance has been addressed throughout the ages in music. On a purely physical level, dissonance is created when pitch wavelengths are slightly slower or faster than others played at the same time. As opposed to wavelengths that travel at double or another multiple of the speed of another, those that don’t fit neatly together sound jarring. They leave us wanting more, needing a resolution and relief to the tension they create.

The risk taken by 19th century composer Richard Wagner illustrates this effect. After centuries of music that relied on harmonies and resonance, Wagner shook the arts world with his opera Tristan and Isolde. The revolutionary “Tristan Chord,” featured in the first two bars, caused a furore among music critics. Instead of creating tension and then providing relief with a resonant chord, Wagner instead let the audience sit in anticipation, and offered no resolution at the end of the musical phrase.

Wagner’s chord, radical for its time, seems insignificant after the musical era of jazz, rock and roll, and heavy metal with the likes of Count Basie, Miles Davis, The Beatles, ACDC, Pink Floyd and Sid Vicious desensitizing our natural resistance to dissonance. Over the years (and centuries) we have steadily developed a capacity to absorb more dissonance in music.

Our tolerance for dissonance

In human behavior, too, we can build this capacity to sit in dissonance to achieve deeper understanding. This has become even more necessary in the fast-moving, volatile, digital age where we are constantly bombarded with new information and challenges that span geographies, cultures and time zones. In many situations, our natural tendency to create resonance as quickly as possible and eliminate dissonance can lead to lost learning opportunities. Most dissonant experiences are opportunities to learn. But does our tendency to get rid of the associated anxiety and discomfort of dissonance prevent us from learning as much as we could? To be intentional around our learning, we need to accept a certain level of dissonance.

The 19th century poet John Keats coined the term “Negative Capability” to describe the discomfort when a person “is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Negative Capability has been appropriated for the study of leadership by Bion,[1] who described it as the ability to tolerate the pain and confusion of not knowing, rather than imposing ready-made or omnipotent certainties upon an ambiguous situation or emotional challenge.

In such a state of discomfort or dissonance, are executives more likely to realize the opportunity to learn, or are they more likely to avoid learning?

Executive roles often do not enable our negative capability unless we know how to nurture it.

By developing our capacity to tolerate and explore our dissonance, we can learn to sense the emotions and dynamics that often occur “under the table” in professional settings, such as competition, betrayal, envy, collusion, anger and disengagement.

Executive learning disabilities

Typically, executives experience hundreds of thoughts every day. These thoughts are caused by problems, issues and dilemmas that need to be solved. Many of these problems and issues generate negative emotions such as confusion, irritation, frustration and anxiety (as well as many positive feelings). The presence of these emotions is a signal that there is potential for learning, but in the cut and thrust of daily life, it is more expedient to get rid of unwanted emotions rather than explore them for learning.

Studies show senior executives can learn, but only if they are motivated to explore the discomfort zones of human behavior. The challenge is made more difficult because organizations and senior roles amplify dissonance – that is, the dissonance, the frustration, the anger, the confusion is more pronounced in these roles. Executives begin to develop learning disabilities due to the very nature of their roles. Learning to recognize them is the ultimate key to addressing and reducing their hold over us.

- Cognitive limits and biases

Executive roles can be overwhelming. It is tempting to maintain order by just sticking to protocol or routine. The 1986 launch of the space shuttle Challenger is a case in point. The evening before the launch, an engineer noticed that launch temperature was forecast for 0 degrees Celsius. He conducted a regression analysis suggesting a higher probability of a critical part cracking at that temperature. His recommendation to suspend the launch, however, created confusion for NASA, who felt uncomfortable by it. In the end, NASA got rid of this discomfort and dissonance quickly enough with the rationalization that “ambient air temperature is not on the protocol for cancelling space shuttle launches.” The results were catastrophic, with all astronauts killed on board.

Four Sources of Executive Learning

When examining executive experiences, we can identify four broad opportunities to learn from dissonance.

New roles and contexts

On assignments in different cultures, executives are frequently confronted with new ways of working and must question their assumptions. New roles (and in particular promotions) can prompt reflection on what contributed to previous success and how the current context and larger responsibility differs. It is not about applying tried and true rules of thumb, but about remaining open to adapting when the realities of the new context clash with lived experience.

Outcomes (success and failure)

While failure can be seen as a good learning opportunity, learning from success is more difficult and rare. The resulting ego boost from accomplishments can blind us to the lessons at hand, resulting in mindless repetition instead of critical thinking about the many reasons for success.

Divergence and antagonism

Often leaders marginalize or fire antagonists, who stoke discomfort and sap emotional energy. But it’s important to acknowledge that there is often an opportunity to learn from antagonists if we care to listen. Where would Harry Potter be without Lord Voldemort? He grew up because of his antagonists.

Life-changing events

It is impossible to separate our professional and personal lives completely. Divorce, death and childbirth all create shifts in the mindsets of leaders. When we take the time to notice and reflect on these changes, we find opportunities to learn and grow.

- Excessive conviction

Senior executives often need conviction. They need to be confident and believe in what they say. Ironically, the more they say something, the more they believe it, and the more confident they become. Over time, being in a senior executive role can simply make them more confident to the point that if they are challenged, they might react with even more conviction, which in turn, might be experienced as hostility or aggression. The inevitable consequence is that other people will stop questioning and challenging senior executives. CEOs often complain that no one tells them the truth, is that because everyone is avoiding the dissonance? Confident leaders with a strong sense of conviction provide a sense of security. It is often difficult for leaders with such conviction to suddenly become curious and open to learning.

- Accumulating success

A natural response to accumulating successes is replication – copy/pasting the solutions that worked in the past to new situations. Because the stakes are high, and the responsibility of executive roles is so great, successful leaders tend to avoid experimenting with new ideas. Their beliefs about what has created success become hardwired as universal formula that can be applied anywhere. After all, most senior executives are hired because of their experiences and what they have learnt from their success, and the role encourages them to play it safe, to replicate past (successful) experiences. While shareholders might appreciate the reliability and responsibility this demonstrates, a lack of experimentation will, by definition, limit learning.

- Fear of vulnerability

Most senior executives hide behind the image of their professional roles to avoid showing their more human and vulnerable sides. They become locked in a role, which constrains and guides their behavior. Status symbols remind them that they have a special role, so they feel the need to hang on to a kind of “tough” persona that guides them in the role. Such a persona causes them to refrain from showing their other sides – the more human side, for example, or the more curious side, or the more playful side. They believe that showing these other sides will make them feel vulnerable or exposed. However, allowing oneself to be vulnerable is to open oneself to new perspectives, to learning and to change.

These four learning disabilities are underpinned by what Anna Freud[2] originally described 80 years ago as “human defense mechanisms.” They include familiar and socially acceptable defenses such as humor, suppression and rationalization, but they may also be underpinned by more aggressive defenses such as displacement (passing discomfort on to less powerful people) and projection. Projection involves believing that other people possess our more undesirable qualities, such as laziness, untrustworthiness or incompetence, and in so doing we deny our own laziness, untrustworthiness or incompetence. All these defenses serve the purpose of getting rid of our dissonance, and make us feel better about ourselves.

The ripples of dissonance

Dissonance can also be a powerful tool for creating change in teams and organizations. While most textbooks suggest that effective leaders create clarity and alignment, the opposite is also true. Effective leaders can also stimulate dissonance in others by creating confusion, anxiety and surprise. Sometimes the best teachers are those who do not give answers, but who provoke a reaction with uncomfortable questions. This forces people to lean into their own dissonance to learn and change. Of course, there is always the risk that they will project their discomfort back onto their leaders and accuse them of being confused, denying their own confusion and missing out on an opportunity to learn and change.

When Anita Roddick, founder of The Body Shop, refused to use delivery vans as a way of promoting the brand in the 1980s, she created surprise and confusion among employees and customers alike. Instead of a catchy Body Shop slogan, she put the following message on the vans: “If you think education is expensive, try ignorance.” There was initial bemusement as customers and employees discussed the slogan, either saying “she’s missing a great branding opportunity” (projection–incompetence) or exploring their confusion. They eventually understood a different purpose, and became loyal to a brand that would become one of the first in the world to take up and demand social responsibility. The CSR message was consistent with no testing on animals, for which the brand became famous, and helped to create an enormous following and loyalty from employees and consumers alike. It can even be argued that this action, and others like it, launched the entire corporate social responsibility movement.

Let us not take dissonance too far. Alignment is essential for execution. Leaders are expected to create clarity and reduce dissonance. But occasionally creating dissonance for others can lead to powerful change. It’s a question of how much dissonance other people can absorb, and how many projections leaders can hold before others explore their own dissonance.

Conclusion

In a fast-changing, dynamic and technology-driven world, leaders will experience dissonance. They will be taken by surprise more often, be confused more often, and become more anxious. As responsibility increases, they will be tempted to get rid of the discomfort of surprise, confusion and anxiety rather than stay with it, and will explore it and learn. The more they explore the dissonance within themselves and their organizations, the more intentional they can be in using that dissonance to learn and change. By doing so, a learning executive can:

- Develop negative capability and lean into dissonance to learn and develop self-awareness.

- Develop a balance between learning and performance, feeding both a desire to grow and the need to feel accomplished.

- Take on a container role, managing and holding others’ emotions in times of uncertainty, ambiguity and change to achieve a broader purpose.

- Make sense of “self in role” and understand how our lives as executives influence us and how we can intentionally influence within our role.

[1] Bion, W. The Psychoanalytic Forum. Vol 2. No.3, 1967