Stéphane JG Girod and Niccolò Pisani, both Professors of Strategy at IMD, consider the reasons behind a fall in profits at Swarovski post-COVID and the steps being taken to pull the iconic company back onto a profitable growth trajectory

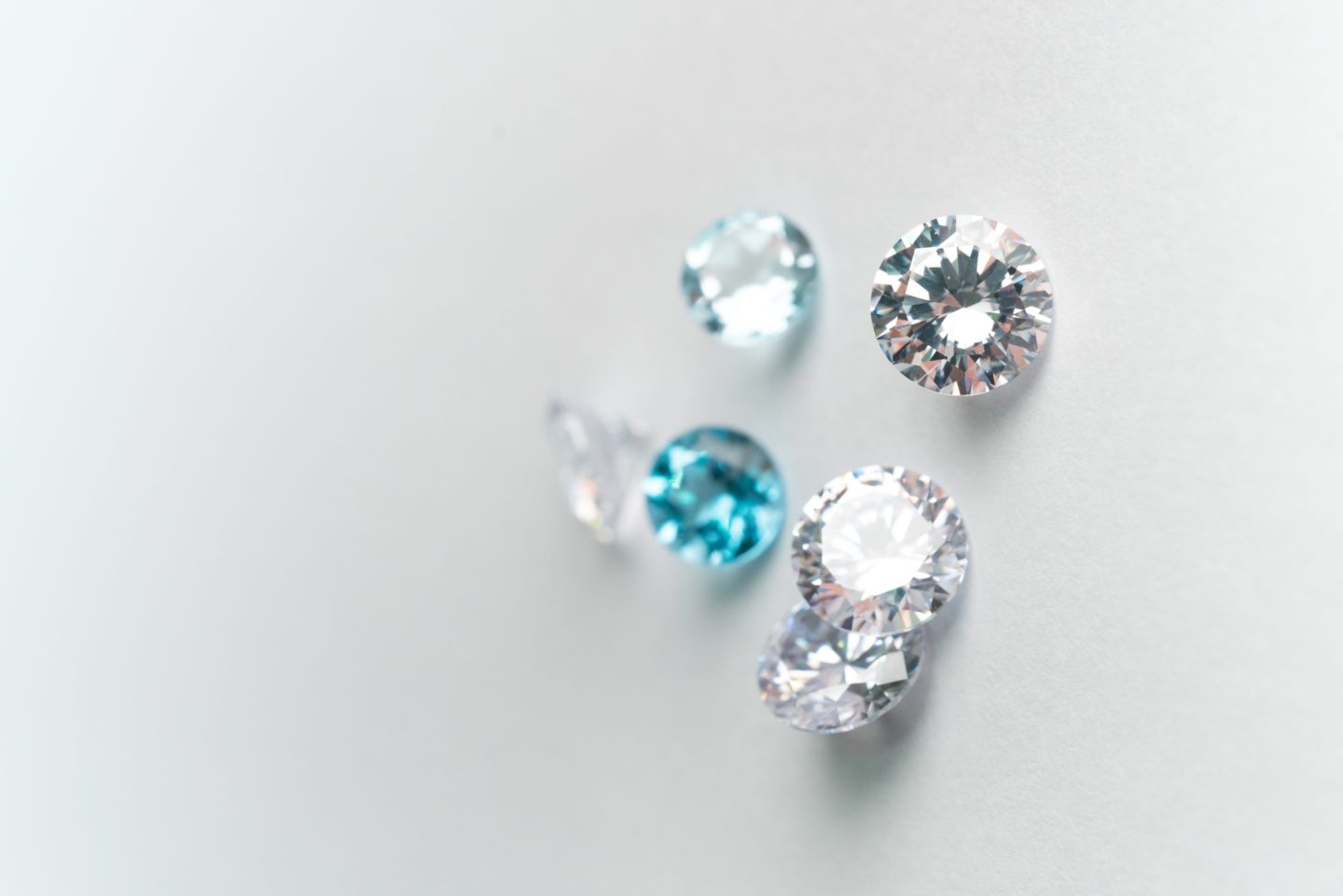

Established in 1895, Swarovski has over the years built a global reputation for its iconic crystals, seen everywhere from the star on the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree to adorning movie and pop legends including Audrey Hepburn, Jennifer Lopez, and recently Harry Styles. Yet a combination of new competitors to the market, changing consumer trends, and, of course, the pandemic saw a dramatic fall in profits and left Alexis Nasard, the company’s new CEO, with some serious strategic decisions to make.

With a family history in crystal craftsmanship, founder Daniel Swarovski’s vision for the company was to “create a diamond for everyone”. Based in Watterns, Austria, Swarovski built strategic access to Paris, where crystal jewelry was…