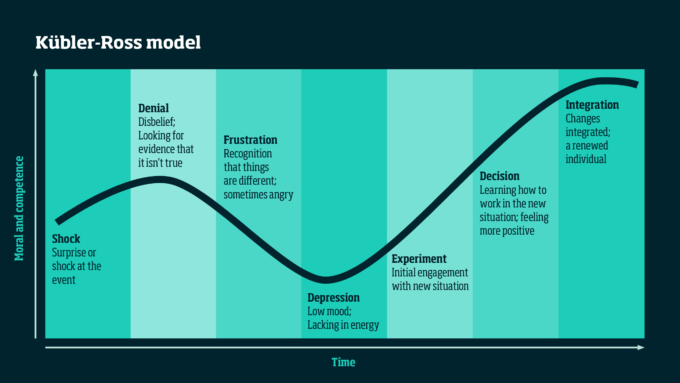

Of particular importance here, the first three stages after the shock itself – denial, frustration (which includes anger and bargaining), and depression – are largely emotional reactions to adversity which reduce the mental and physical capacity to act. After reaching a nadir with depression, the cognitive system kicks in. People then start to experiment and engage with the new situation. This allows an active decision to learn how to work in, and ultimately live with, the new situation. Finally, people integrate the change into their lives, which can give some sense of meaning to what they went through.

Higher or lower levels of resilience arise from individual or group attributes which let people minimize the debilitating aspects of adversity and focus on beneficial ones. Broadly speaking, four qualities are important. These take different, albeit related, forms among individuals and groups.

For the former, the first attribute is realism married to self-awareness. Optimism will not necessarily help: optimists can end up losing hope if their expectations of a problem diminishing quickly go unfulfilled. Instead, a staunch sense of reality, including what a person can and cannot do, is far more useful. Second comes resourcefulness, so the individual can, despite anxiety or fear, as questions such as “What can I do?” and “What are my options?” Their choices might be very limited, but resilient people find them. It is the opposite of self-victimization.

The third characteristic, which grows from the first two, is that resilient people use their agency, applying pragmatically any resources they can find to overcome their crisis, and ability on which survival may depend. This is not hyperbole. Resilience is a human survival skill in the face of adversity. Finally, resilient people, at the end of the process, ask, “What can I learn from this?” In this way, they find meaning in what took place, can deepen the purpose they feel in their lives, and are also better prepared for the next period of disruption.

The parallel attributes for teams, including corporate boards, begin with group members having a somewhat accurate mental model of the strengths and weakness of both the team as a whole and its constituent individuals. This requires not just mutual understanding but open channels of communication as a crisis unfolds. The team equivalent of individual resourceful pragmatism is the capacity to improvise and to leverage the experience within the group. This helps explain the common academic finding that well-managed diverse groups tend to outperform ones made up of similar people in crisis: the former are more likely to have a wider range of experience. Nobody knows which experience might be needed when, so the more diverse at team is, the better prepared for the unexpected.

The third attribute of resilient groups is potency – the ability to act with the right blend of confidence and caution even when the team’s – or the company’s – existence might be at stake. Here, high-performing and resilient teams differ. In a safe, stable environment, the former may thrive with an attitude of “Go, go, go, go, go, the sky’s the limit!” But a resilient team is able to dial back on confidence and balance it far more prominently with caution to ensure survival. Lastly, resilient teams also need to go through a process of reflection and sense-making. For this to occur, a psychologically safe environment is a fundamental pre-condition.

Steps towards inculcating resilience

The good news is that resilience can be learned. The bad news is that it may not be straightforward – or pleasant – to develop.

Audio available

Audio available