Stress busters: How to help employees help themselves

Dr. Rachel Lewis explores how empowering teams to co-create solutions can reduce workplace stress and boost wellbeing...

by Richard Roi, Misiek Piskorski Published December 17, 2021 in Human Resources • 13 min read

Ask any CEO, CHRO, or C-level leader about the most pressing problems they face, and you inevitably hear two things: talent and transformation.

Inquire about talent and you will receive a long list of seemingly insurmountable and related problems: the best talent gets great outside offers and leaves, but the remaining talent bench ready to take over their jobs is never deep enough. So executives are promoted to senior positions, even though they do not have the requisite skills or leadership competencies, and companies then invest millions of dollars to develop their leaders in an attempt to close that competency gap, often with minimal results. It’s not a surprise that many top executives report that talent management is a tough nut to crack.

To understand just how widespread this problem is, we studied 15 large companies in different industries across the world. For each company, we created a composite measure of talent management success that combined the company’s self-assessment, concrete measures of improvement in the competencies of its leaders (attributable to talent management activities), as well as our subjective assessment of the company’s talent management.

We quickly discovered that most companies struggle with talent management. However, we also identified a handful of companies that have truly mastered it. As we looked at what unites these, we found that the key to their success lies in very tight integration of all talent management activities to company strategy and to each other. Even relatively minor failures to integrate any of the activities with others quickly undermine the entire talent management endeavor, leading companies to struggle. At first sight, this may seem obvious. After all, how hard could it be to integrate development activities? In reality, talent management is difficult to manage successfully because it encompasses a diverse spectrum of activities:

However, as we describe below, there are systematic integrations required at each of the four following steps that will allow for better outcomes.

Ambidextrous leaders who can both transform an existing business and build a new one from scratch are rare ... with most executives being good at one or the other.

The first thing we noticed when we studied companies that have mastered talent management is how precise they are about the concept of transformation and the leadership behaviors associated with it.

CEOs and other senior leaders of these companies routinely recognize that they are faced with two simultaneous transformations. They must fundamentally rethink and transform how the existing business operates in order to ensure sustained growth and profitability. At the same time, they need to transform the company strategy to grow new revenue sources from new products often with new business models.

One group CEO, who leads a 100-year-old bank, put it this way: “At 9am, I am meeting with bank managers, talking about how to transform our small-medium business customers loan application process to make it more streamlined while reducing our risk for non-performing loans with these customers. At 10am, I am meeting with a digital platform partner to explore how to quickly establish a seamless mobile payments platform, to take advantage of the bank’s large customer base and to displace a competitor who is growing quickly in the mobile payments segment.”

Achieving these goals requires frequently opposing sets of leadership behaviors. Leaders need to be able to switch between improving business as usual, driving transformational change, and then turning it into business as usual. We call this ambidextrous leadership. For example, an ambidextrous Chief Marketing officer can transform the existing business from mass-marketing to 1-to-1 marketing, and then develop procedures that ensure the new method of marketing is executed with excellence. Similarly, an ambidextrous Chief Strategy Officer who developed a new business line will not make it sustainable unless he also builds a solid organization around it.

Such ambidextrous leaders who can both transform an existing business and build a new one from scratch are rare, with most executives being good at one or the other. And yet, they are central to achieving the strategic goals of their organizations.

In fact, the companies that excelled at their talent development strategies recognized this explicitly and created executive performance models that required leaders to master both types of behaviors. As we examined these models in detail, we found that the most comprehensive ones emphasized at least five different core skills: leading strategy, execution, stakeholders, people, and self. And then, on each skill, the models called on leaders to exhibit these radically different behaviors or, in other words, to be ambidextrous. While the details of each model vary, the composite best-in-class ambidextrous performance model usually entails the following behaviors.

To be ambidextrous when it comes to strategy, leaders need to be both transformers creating new businesses, and operators who constantly adjust the strategy in response to short-term market changes. When leading execution, they need to be both experimenters, constantly looking for better ways to deliver value, while at the same time driving operational excellence and profitability using proven systems and processes. When leading stakeholders, it is necessary to know when to use informal power and networks to influence and move things forward, and at the same time know how to use power arising from the formal structure and governance processes of the organization. When leading people, the challenge is to flex between using a coaching and empowering style of management and to know when to apply more formal performance management processes to ensure team and individual contribution and performance. The final scale involves leading yourself. Since a successful corporate leadership career is more like a marathon than a sprint, a daily routine is needed to maintain energy, focus and stamina. It is therefore important that time is invested in clarifying personal values and vision as leaders to promote courage and resilience, while, at the same, taking good care of mental, emotional, and physical wellbeing on a regular basis.

A senior leader’s activities include: leading business (strategy and execution, above), leading people (both teams and individuals, above) and leading themselves (not pictured). For each dimension, he or she must master two opposing behaviors – for strategy, for example, the leader must be both transformer and operator. To lead stakeholders, the leader must know when to use informal networks to move things forward, and how to use power arising from the formal structure and governance processes of the organization. We ask executives to rate themselves in the charts above. Most of the time, executives will score themselves highly on horizontal dimensions which represent business-as-usual behaviors. A smaller percentage will rate themselves in the top right corner, claiming that they possess both business-as-usual and transformational behaviors on any of the scales. And even a smaller percentage will do so on all five scales.

How would you judge your own skills? Please use the boxes above to assess your own ambidexterity, then reflect on what it would take to make you more ambidextrous.

In our research, we found that companies that have mastered talent management, there is a tight link between their executive performance model and their assessment strategy. All companies deployed a form of self-assessments, 360-degree assessments, or even expert assessments. But companies that are the most successful at talent management derived these assessments from carefully thought-through executive performance models; assessment must be based on expertise. In contrast, those that did not see solid results usually asked their executives to fill out personality assessments and deployed systems of measuring capabilities with no clear link to the strategy of the company, or they focused on business-as-usual capabilities only.

When we have undertaken assessments focused on ambidexterity, we have discovered just how rare these leaders are. For example, in a sample of 450 senior executives from 10 companies, each in a different industry across the globe, we found that just 12% of them were ambidextrous across all five leadership skills. Roughly half of the leaders that we studied were ambidextrous on at least one skill, but for all other skills, leaders were either strong on the business-as-usual dimension, or the transformational dimension, but not both. All others had their work cut out to become ambidextrous on all five dimensions.

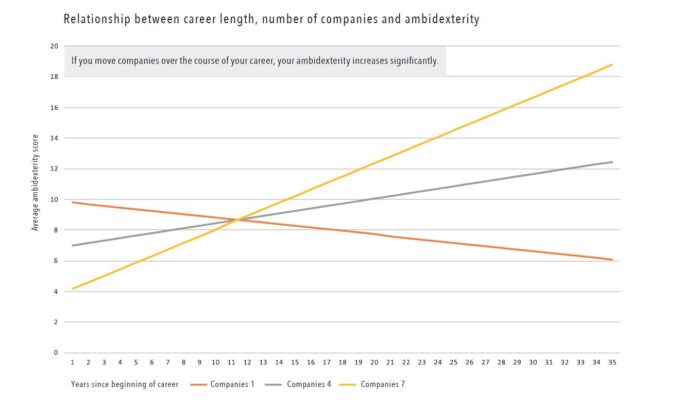

These kinds of assessments allow companies to run extensive analytics to understand the composition of their executive ranks to decide how best to develop them. For example, our analysis of the same sample of senior executives revealed that, on average, as executives gain another year of experience, their overall ambidexterity score increases (calculated as a product of ambidexterity scores on all five skills). This is not surprising in that every year gave executives new opportunities to hone different skills, thereby making them increasingly ambidextrous. This effect held only for executives who also changed companies during their careers. In contrast, executives who remained in the same organization, additional years as executives actually made them less ambidextrous. This is likely because they were not challenged in their current company to develop new skills (or because non-ambidextrous leaders were unable to get new jobs).

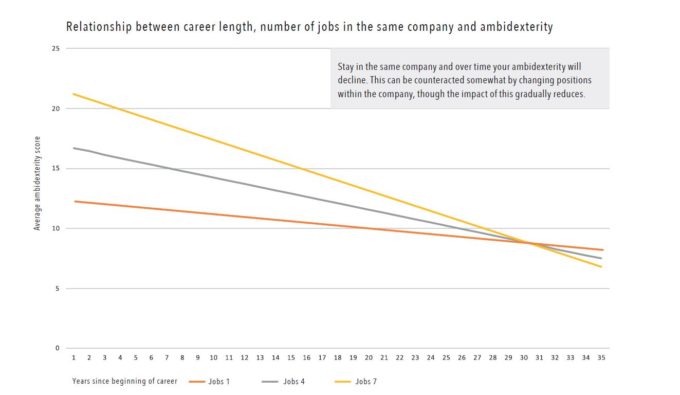

Changing jobs inside the same company also makes leaders more ambidextrous, according to our research, as it allows them exposure to new skills and challenges. This effect was largest for leaders who had just started their careers. Circulation of such leaders could increase their ambidexterity by as much as 50%. In contrast, those who have many years under their belt, and get circulated in the same company, only experience 10-15% increase in their ambidexterity. This smaller increase can be attributed to limited learning opportunities by circulating in the same company.

Our research further shows that the executive performance model, assessment strategy, and the way development plans are constructed are closely linked in companies with successful talent management models.

Specifically, these companies explicitly expect their leaders to become ambidextrous on all five skills. Executives are measured across the five skills, and assessed where improvement and training are needed. A close collaboration between the head of talent and head of leadership development is used to assemble a set of activities that target the skills needed.

These activities include development to improve ambidexterity on a particular skill, exposure in a controlled environment where the leader can see the skill applied in an ambidextrous fashion, and experience where the leader can practice the skill in a new business context. The mix between these activities needs to be carefully calibrated to a leader’s situation, and particularly to her years of experience. As we discussed in the previous section, leaders with significant experience will benefit more from exposure (e.g., being moved to a startup owned by the company in question) and education (e.g., executive training) than those with fewer years under their belt, who will benefit more from experience (e.g., being moved to a different function in the same company).

Much of what we discussed above is intuitive and commonsensical. And yet, in our research we found that only a very small number of companies tightly link prescribed actions to the results of the assessment, which in turn is based on a highly prescriptive performance model. Instead, most companies put their executives through general skill-building activities that may be unrelated to their precise needs; or they allow executives to pick their own development activities, which target skills unrelated to key performance variables, or skills where there are no gaps present.

As we spoke with the heads of talent management and the heads of leadership development of the companies we studied, it became obvious that the primary reason for this disconnection lies in separation of the two functions. Even though the heads of these functions often report to the CHRO, they rarely share data, targets and budgets. This then leads to removing the tight connection between the performance model, the assessment, and the remedial actions, which in turn contributed to low ROI on talent management investments.

The final point of distinction between companies that have and haven’t mastered talent management lies in the execution of the development plans.

The best companies we studied go to extreme lengths to ensure that all the activities prescribed in the development plan are actually executed. Some companies that failed to master their talent management strategy did not execute up to 75% of development tasks they asked their executives to undertake. Fire-fighting, unexpected external environment changes or lack of oversight were the most frequent explanations for this poor state of affairs.

The best companies not only executed on the development plans, but they did so with the utmost care. For example, talent and leadership development leaders in one company we studied contacted every coach and every executive education professor who would interact with their executives to discuss assessment results and competency gaps for each executive. After coaching or executive education took place, these leaders would contact the coaches and professors again to debrief how much the executives were able to advance towards closing their competency gaps. This perhaps somewhat extreme approach yielded excellent results in advancing leaders’ competency set.

Finally, these best companies would then continue to assess their executives in question to monitor progress, and take remedial actions quickly if prescribed actions yielded no movement on skills of interest. In fact, every company we studied that mastered its talent management used such interim assessments to change providers or change the material they used for development purposes. As obvious as the last step is, we were surprised just how few companies monitored progress of their prescribed activities in real time and adjusted the prescriptions.

Companies routinely invest millions of dollars in developing their talent pipeline. Most fail to see a significant return on their investment, but a small set do. Our research helped us uncover one key characteristic that differentiates the former from the latter, which is tight integration of all talent development activities. Although it is not hard to imagine how this integration can take place, and in many ways such integration is almost obvious, only very few companies engaged in it, leading to the observed outcome. We hope this insight will alert the talent and leadership development executives to just how important this integration is and get them to work together in service of growing and progressing the future leaders of their company.

Affiliate Professor of Leadership and Organization at IMD

Ric Roi is Affiliate Professor of Leadership and Organization at IMD. He is a senior business psychologist and advises boards and CEOs on matters related to board renewal, CEO succession, top team effectiveness and leadership transitions.

Professor of Digital Strategy, Analytics and Innovation and Dean of Executive Education

Mikołaj Jan Piskorski, who often goes by the name Misiek, is a Professor of Digital Strategy, Analytics and Innovation and the Dean of Executive Education, responsible for Custom and Open programs at IMD. Professor Piskorski is an expert on digital strategy, platform strategy, and the process of digital business transformation. He is Co-Director of the AI Strategy and Implementation program.

June 23, 2025 • by Rachel Lewis in Human Resources

Dr. Rachel Lewis explores how empowering teams to co-create solutions can reduce workplace stress and boost wellbeing...

May 13, 2025 • by Luca Condosta in Human Resources

The CDO, formerly a figurehead for regulatory compliance, is now a key driver of company strategy. Luca Condosta describes the essential skills that CDOs require to turn DE&I concepts into actual commercial...

April 30, 2025 • by Manju Ahuja in Human Resources

The pandemic sparked a shift to remote work that’s proving hard to reverse. According to Prof. Manju Ahuja, hybrid models are the new norm—driven by employee expectations, technological advances, and a changing...

April 29, 2025 • by Michael D. Watkins in Human Resources

Use this diagnostic tool and roadmap to rebuild trust and confidence within dysfunctional teams – the first crucial steps toward a future of high performance....

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience