Busting the myths of M&A: 4 steps to success

Busting the myths of M&A: New research reveals why old merger strategies fail and how fresh thinking can lead to lasting value for both sides of the deal....

by Patrick Reinmoeller Published November 23, 2023 in Finance • 8 min read •

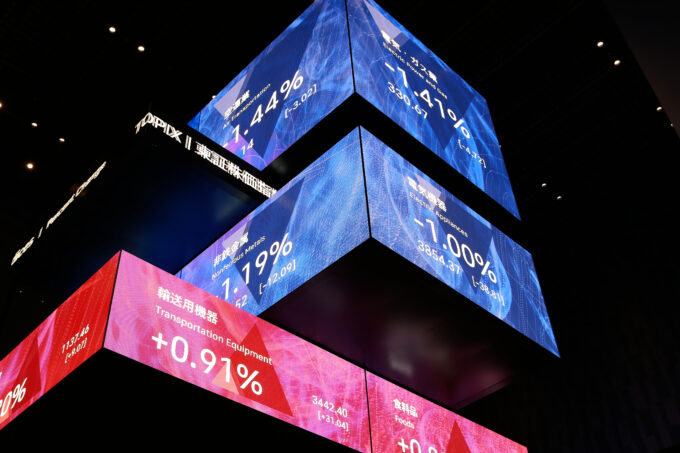

After decades in the wilderness, Japan’s stock market is back in fashion and there’s one trendsetter to thank: billionaire investor Warren Buffett.

In 2020, Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway bought into five Japanese trading houses – Itochu, Marubeni, Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Sumitomo – and this year increased its holdings in each of the companies to an average of 8.5%. Buffett aims to hold them for the long term and has announced plans to raise his stakes to as much as 9.9%.

Buffett’s investments have put wind in the sails of the Japanese stock market, sending shares in the TOPIX Share Price Index or the Nikkei Stock Average Nikkei 225 to multi-year highs.

So, what caught Buffett’s eye in Japan?

Known as the sage of Omaha, Buffett is one of the richest men on the planet. Together with Charlie Munger and their team, he built Berkshire Hathaway into a best practice for diversified conglomerates with a stock portfolio worth $350 billion plus a $150 billion war chest.

While the companies that are part of Berkshire Hathaway’s portfolio have changed over the decades, Buffett’s approach to investing has remained consistent. Commonly known as value investing, this approach relies on finding firms that are undervalued but have high growth prospects and sticking with these companies over a prolonged period.

For a long time, Japanese shares have been unpopular with foreign investors, which depressed valuations. Investors were put off by the bureaucratic corporate structures, a lack of women and general diversity in the top ranks of firms, opaque corporate governance, and a feeling that executives culturally favored harmony over constructive discussion.

Since the global financial crisis, things have started to change, albeit slowly. Extremely low interest rates pushed down the value of the Yen, which lost 50% of its value between 2016 and 2021, making Japanese stocks more attractive for holders of strong currencies, such as the Swiss Franc.

Foreign investors have started to return, and by 2022 the number of shares held by foreigners had risen to more than 50%. There is progress on board diversity too. A recent Egon Zehnder survey of 127 Japanese companies with a combined market capitalization of €8 bn, showed that more than 40% of the companies surveyed had one or more non-Japanese directors, compared to 32.9% in 2020. The percentage of non-Japanese directors on the boards of these companies grew to 8%, up from 6.4% in 2020.

Despite this, Japan’s top-tier firms remain undervalued. The price-to-book ratios, which measure the market value relative to its book value, of roughly half the companies listed in the top tier of the Tokyo Stock Exchange hover around or even below 1.0. This means Japan’s price-to-book ratios are highly attractive for value investors compared to the US and Europe. Less than 40% of Japan’s listed companies have P/B ratios higher than 2; in the US this is more than 75%, and in Europe more than 50%.

Alongside a fall in the value of the currency and low P/B ratios, a third factor has increased investors’ confidence in the Japanese market.

Since April 2023, Hiromi Yamaji, a former Nomura banker who is head of the Japan Exchange Group (JPX), which controls the Tokyo Stock Exchange, has started to shake up the traditional business establishment by vigorously advocating for change and shaming Japan’s corporate leaders for failing to achieve higher valuations for the companies they lead.

Shame is known as a powerful sanction in Japan where others’ evaluations of their companies’ substandard valuations can cause corporate leaders and their employees to suffer shame. Consequently, a banker suggests that “Yamaji-san is the biggest activist in Tokyo at the moment”. Yamaji’s “shame regime” will launch on 15 January 2024 and is expected to expose the underperformance of companies and their top management. According to the Financial Times, expectations are that during his four-year tenure (which ends in 2027), he might just shame leaders into delivering higher returns even faster. Hardly any development could be more welcome to value investors like Buffett, who likes to buy low and waits for the rise.

With the Bank of Japan laser-focused on reviving Japan’s languishing economy, Buffett understood that interest rates would remain lower for longer than many countries in the West. Using his heft and global renown, Buffett was able to convince Japanese creditors to give him even better rates than the already net zero costs in Japan. By borrowing Yen, Buffett eschewed currency risks. The next step was to find attractive investment opportunities in Japan.

The traditional value investing playbook would see Buffett investing in the Japanese trading company that offers the highest upside. In this case, however, Buffett decided to invest in five rivals in equal measure. Buffett’s move appears more like a shotgun approach than a strategy. If none of these general trading companies stands out, textbooks suggest, they all have no, or at best “bad” strategies.

Three logics help explain why Buffett opted for companies with “bad” strategies.

First, on a micro scale, each of the Japanese general trading companies has a good track record. They are stable and highly profitable, pay high dividends, and increasingly also buy back shares. This makes each of them attractive from a financial perspective, even if their results are strongly correlated.

Second, logic suggests that diversified portfolio companies invest to maintain their diversified portfolio. When Berkshire Hathaway, a conglomerate, accumulated shares in Japanese conglomerates, it bought what it knows and maintained a high degree of diversification, albeit in one country in a geopolitically critical region.

Third, for a long time, strategy has sought to find ways to make companies stand out, and value investors have sought to identify individual companies with “moats”. Simply put, like those that surrounded medieval castles to protect turf and treasure, moats give companies a competitive advantage that makes it easier to protect their market share and profitability over time. Examples of modern-day moats include high switching costs, intangible assets, network effects, cost advantage, and efficient scale.

Each of the five trading companies appears to have a very similar micro-moat, a moat protecting one entity. However, more decisive is that they together benefit from a macro-moat: the moat around trading for Japan.

Consider that the share of trade as part of Japan’s GDP was 37.3% in 2021. These trading companies are supplying the Japanese economy with the resources that the Japanese economy needs; about $732 billion in exports and $700 billion in imports. Scarce in natural resources, rich in sophisticated companies and an advanced economy, its resource demands are considerable – and will stay so, long into the future.

While these trading companies are individually not bestowed with strong competitive strategies, collectively these companies profitably and reliably dominate Japan’s trade. Their competitive advantage is protected by the moat around Japan. By investing in these five trading companies that collectively dominate trading with Japan, Buffett bought a slice of Japan’s economy.

Many super apps like Grab, Alipay, and WeChat aimed at grabbing slices of country economies but most failed or fell out of favor. Berkshire Hathaway has revived interest in a staider set of companies: traditional trading companies. It announced that, without board approval, it would not increase the stakes in these five companies beyond 9.9% and has now invested $6.25 bn in Japan. Yet, four consecutive quarters of divestments in US blue chips raised Berkshire Hathaway’s cash to a record sum of $157bn in the fall of 2023. Buffett needs to find other industries that are protected by a moat like that of Japan. For now, he is making Japan his home away from home.

Professor of Strategy and Innovation at IMD

Patrick Reinmoeller has led public programs on breakthrough strategic thinking and strategic leadership for senior executives, and custom programs for leading multinationals in fast moving consumer goods, telecommunications, pharmaceuticals, healthcare, and energy on developing strategic priorities, implementing strategic initiatives, and managing change. More recently, his work has focused on helping senior executives and company leaders to build capabilities to set and drive strategic priorities.

July 7, 2025 • by Patrick Reinmoeller, Markus Nicolaus in Finance

Busting the myths of M&A: New research reveals why old merger strategies fail and how fresh thinking can lead to lasting value for both sides of the deal....

April 24, 2025 • by Jerry Davis in Finance

Many regional developers have tried and failed to emulate Silicon Valley’s VC-driven model for innovation. Detroit, the birthplace of Ford, is following an alternative route – with promising results....

Audio available

Audio available

April 23, 2025 • by Karl Schmedders in Finance

CFOs must drive a financially disciplined way to manage environmental risks amid growing pushback against environmental sustainability efforts, explains IMD’s Karl Schmedders....

April 11, 2025 • by Jim Pulcrano in Finance

IMD's Jim Pulcrano interviews Ruchita Sinha, General Partner of venture capital firm AV8 Ventures, and explores her approach to early-stage investing....

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience