Busting the myths of M&A: 4 steps to success

Busting the myths of M&A: New research reveals why old merger strategies fail and how fresh thinking can lead to lasting value for both sides of the deal....

by Raphaël Grieco Published November 1, 2023 in Finance • 7 min read

According to various estimates, between 75% and 94% of startups fail. The odds aren’t much better than gambling. While this is a difficult number to measure and prove, it nevertheless underscores the high-stakes, high-reward nature of investing in Venture Capital (VC), a form of private investment that focuses on financing early-stage, high-potential, high-growth startups.

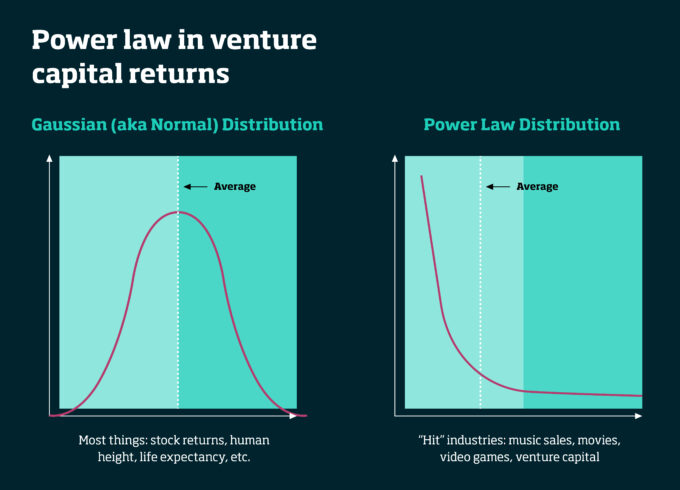

Since most of these startups will fail to reach product-market fit, go public, or find a buyer to provide a positive exit to all equity holders – that is paying back the original investment and generating a net profit – VC funds are on the hunt for a small number of investments that will yield returns far greater than the rest, offsetting the losses incurred by others. This is known as the Power Law, a mathematical concept first developed by 19th-century Italian economist and sociologist Vilfredo Pareto, who identified that 20% of his pea pods produced 80% of the peas.

Today the Power Law is visible in many fields ranging from economics and sociology to physics and venture capital. Taylor Swift and Harry Styles have many more listeners than thousands of other artists put together, while JK Rowling has sold far more books than many authors combined. In the VC world, this means that funds ideally want to uncover a startup where the realized returns from a single investment may outweigh the combined returns of all the other investments in the fund.

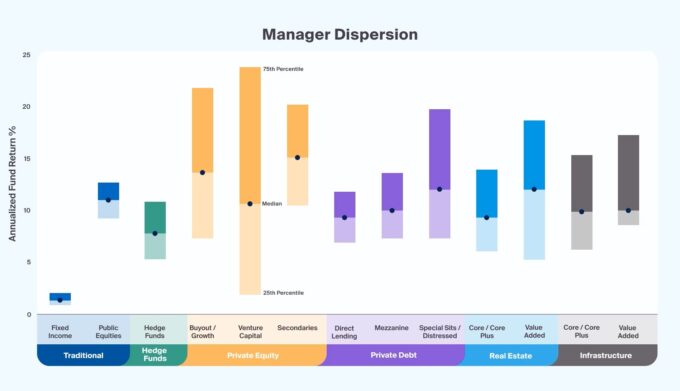

The strategy deployed by VC funds is deliberately different from traditional diversification, where investments are spread across a broader portfolio to minimize losses. With data suggesting that 65% of VC deals return less than the capital that was invested in them, VC investors are typically comfortable with higher levels of risk compared to investors in other asset classes (even in private equity), and devote their resources and efforts on identifying and helping the high-potential outliers that will generate profits for the rest of the fund. These investments are often directed towards industries such as technology, biotech, and other innovative sectors.

VC funds don’t only provide capital to startups in exchange for an equity stake in the company. They may also offer the guidance, mentorship, and connections needed to help them succeed. As the startups grow and reach key milestones, they take on additional funding rounds to further develop and expand their operations. Venture capital is therefore a critical driver of economic growth, job creation, and technological advancements, as it plays a vital role in shaping the business scene by supporting the birth and growth of pioneering companies.

One notable VC success story is Facebook’s early investment by Accel Partners in 2005. They invested $12.7m for a 15% stake, valuing the company at nearly $100m. Facebook’s innovative approach to connecting people online attracted Accel, and its support during those early stages paid off. With subsequent VC funding, Facebook grew to become a tech giant, going public in 2012, raising $16 billion, and reshaping the global tech and social media landscape. Facebook’s journey highlights how venture capital can propel startups into major industry players, delivering substantial returns for both investors and founders.

In the context of the Power Law, Facebook’s eventual success, with billions of users and a market capitalization in the hundreds of billions of dollars, greatly outweighed Accel Partner’s initial $12.7m investment. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly how much that initial investment returned, but sources estimate between 247x and 700x at the time of the initial public offering. This clearly highlights how a relatively small number of VC investments can significantly impact the venture capital portfolio’s overall returns by not only paying back the cost but also generating all the profits at the fund level.

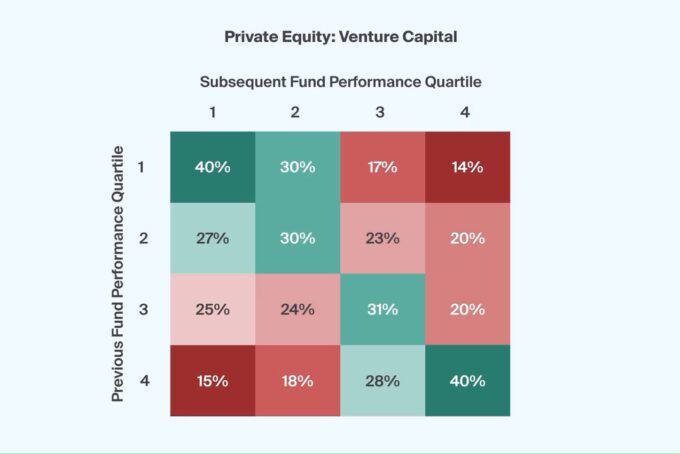

When it comes to venture capital investments and assessing your own risk tolerance, understanding the difference between Limited Partners (LPs) and General Partners (GPs) is crucial. LPs usually have a lower risk appetite compared to GPs due to their passive roles and reliance on experts. GPs, on the other hand, actively manage investments and take a more hands-on approach to risk. This risk gap highlights the core contrast between these investor types in the VC world. As a result, diversification in VC involves spreading exposure across different GPs rather than diversifying the portfolio of companies directly.

Let us take a closer look at the way investments are made and portfolios are shaped. For example, a VC fund that has invested in 25 different portfolio companies will need to get a 25x return for an investment just to return the capital and before generating profits. (This assumes that all investments are the same size without considering costs).

LPs are usually expecting a VC fund to generate 3x net return on invested capital. In the above example, a real “fund-returner” needs to get a three times 25x return, i.e., 75x. In reality, only a few VC investors achieve this performance and consistently return funds greater than three times net investment. Some VC firms, however, get one, two, or even three fund returners per fund. For instance, Union Square Ventures’ first-ever fund ($125m) turned out to be one of the best-performing VC funds in history. The VC firm’s 2004 vintage was reported to have returned about 14x on total invested capital as of 2018. Such outperformance was driven by a portfolio that included video game developer Zynga, social networking sites Twitter and Tumblr, job listings site Indeed, and vintage and handmade e-commerce company Etsy.

Traditional diversification aims to spread risk by investing in various asset classes, including stocks, bonds, and illiquid assets like hedge funds, real estate, and private equity. Venture capital, however, focuses on high-risk, high-reward assets, challenging diversification principles. To diversify your VC strategy, start by understanding the difference between generalist and specialized VCs.

Generalist VCs invest across industries and stages without a specific focus. For instance, Sequoia Capital backs companies in technology, healthcare, and more. They embrace the Power Law but across a wider range of investments.

Specialized VCs concentrate on specific industries or sectors like technology or healthcare, gaining deep expertise. Entrepreneurs prefer them due to streamlined communication and shared knowledge, making discussions about their businesses more efficient.

“To diversify your VC strategy, start by understanding the difference between generalist and specialized VCs.”

Historically, LPs have been hesitant to invest in specialized VC funds due to rapidly changing innovation landscapes. However, this appears to be changing, with a major European tech report finding that 22% of LP respondents in a 2021 survey preferred investing in specialist VC funds versus 17% who picked generalist VC funds.

Venture capital is a complex game of risk and reward. It’s all about aiming for a big return, even if this is hard to come by. The key principle to bear in mind is the Power Law, which says that a few select investments can make up for those that don’t pan out. This challenges the traditional idea of spreading your investments around to reduce risk.

But here’s the catch: the approach to diversification depends on the type of investor. LPs, playing more passive roles, tend to prefer safer, low-risk strategies. They typically put their money into broad, generalist venture capital funds. This divide between LPs and GPs reveals a significant gap in the venture capital world. It’s a complex environment where the quest for exceptional profits is coupled with a keen understanding of the different risk appetites.

Research Associate at the IMD Venture Asset Management Initiative

Raphaël Grieco is a former Research Associate at IMD for the Venture Asset Management Initiative, drawing on over 15 years of leadership experience at the intersection of cross-asset wealth management and technology. Raphael specializes in early-stage venture investing, multi-support educational content creation spanning written and audio formats, as well as building entrepreneurial ecosystems focusing on technology (including crypto and web3).

July 7, 2025 • by Patrick Reinmoeller, Markus Nicolaus in Finance

Busting the myths of M&A: New research reveals why old merger strategies fail and how fresh thinking can lead to lasting value for both sides of the deal....

April 24, 2025 • by Jerry Davis in Finance

Many regional developers have tried and failed to emulate Silicon Valley’s VC-driven model for innovation. Detroit, the birthplace of Ford, is following an alternative route – with promising results....

Audio available

Audio available

April 23, 2025 • by Karl Schmedders in Finance

CFOs must drive a financially disciplined way to manage environmental risks amid growing pushback against environmental sustainability efforts, explains IMD’s Karl Schmedders....

April 11, 2025 • by Jim Pulcrano in Finance

IMD's Jim Pulcrano interviews Ruchita Sinha, General Partner of venture capital firm AV8 Ventures, and explores her approach to early-stage investing....

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience