How to manage power dynamics in high-stakes negotiations

Former FBI agent Joe Navarro explains how to leverage non-verbal cues, manage power dynamics, and build trust to overcome deadlocks in negotiations....

by David Bach Published January 17, 2024 in Competitiveness • 7 min read

Recently, when thinking about the increasing importance of geopolitics for business leaders, I sketched out what I saw as the three biggest questions we face in the year ahead. The exercise had me reflecting on the cracking of the old liberal international order and what it might take for it to be restored.

Below are the three questions I believe will together shape the next decade. I urge business leaders to take heed:

Let’s take a look at each of these in turn.

China’s economy doesn’t look great; forecasts are gloomy. Over the past year, while the US’s Dow Jones Industrial Average has surged, the Shanghai stock exchange has slumped.

So, how bad does it look on the ground and what might happen next? To get answers, I continue to watch the three main pillars of the Chinese economy. They are:

In brief, both FDI and exports have been hurt by the fact that countries in the West have been trying to diversify their supply chains and mitigate geopolitical risks. New factories that might have been built in China are currently going up in Vietnam and India, for example. Many products typically sourced from China – from computer chips to surgical masks – are now coming from new places.

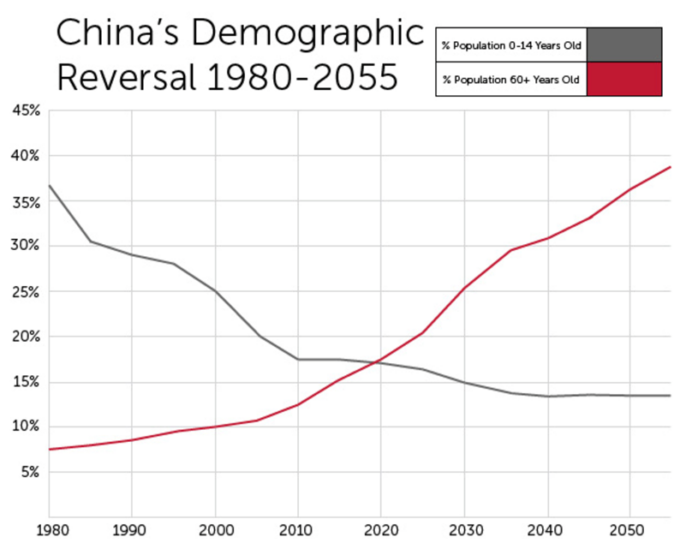

Meanwhile, real estate is the most domestic of the three pillars, and it’s also, I think, the most worrisome for geopolitics. Dragging down Chinese property values are issues like overbuilding and dodgy loans. Another issue here is demographics: China’s population is aging. Back in 1980, the population was young. But by 2020, the number of Chinese over 60 began to outnumber those under 14, and the trend is projected to continue for the next few decades.

Source: UN Population Division (2015) via “Sustainability Insights: China’s Elderly” (2016)

Real estate and demographic trends point to the possibility of growing domestic discontent. In many ways, China’s upper middle class has enjoyed a sort of social contract with the Chinese government. That is to say, in return for material comfort and growing wealth, China’s upper middle class has acquiesced to the Communist Party of China (CCP) and its leader Xi Jinping. But if this group feels the sting of a real estate decline and/or other economic hardship, the party’s legitimacy could slowly erode among this key demographic.

What might the Chinese government do to distract from domestic discontent? Remember the 1997 movie Wag the Dog? Creating an external conflict was seen as the answer to domestic political problems. Based on what I’ve seen, especially during a recent trip to Beijing, I think the United States is looming as Public Enemy Number One for Chinese citizens. The amount of anti-American sentiment I saw on the ground was frankly shocking. China blames the United States for its protectionist policies, Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, the Federal Reserve’s setting of interest rates, and so on.

In sum, if China’s domestic economy looks worse, China-US tensions could escalate to new uncomfortable heights, with spillover effects felt all over the world.

On 20 February, Russia’s latest invasion of Ukraine will turn two years old. What was supposed to be a quick invasion has some developing “Ukraine fatigue”, as the Financial Times put it. But I think leaders should stay sharply aware of the likelihood of a decisive turn this year, even as time seems to drag on.

Some military analysts I’m following compare the war in Ukraine now with what happened near the end of World War I. That was when neither of the two sides were gaining nor giving up much territory. But the lack of movement wasn’t for their lack of military efforts: the pressure on the fronts was so high that when one side gave, it was like a dam bursting. And then World War I was over.

In Ukraine, accumulated pressure from both sides is intense now and running through both Russian and Ukrainian resources. Because of this accumulated pressure, a resolution in 2024 is looking increasingly likely, more likely than it was in 2023. Of course, what happens with China has some bearing, as China is an important ally and support for Russia. On top of that, what happens in the United States matters, as its military support (along with Europe’s) is crucial for Ukraine. While it’s hard to predict the war’s winner now, it’s relevant to watch both China and the US.

In November 2024, US voters go to the ballot box to decide who will be their next leader, and thus the leader of one of the world’s top superpowers, with repercussions to be felt all over.

Former President Donald Trump is the more authoritarian option, and someone who has repeatedly questioned the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and its commitment to mutual defense for Europe and other traditional allies. This election comes at a time of surging support for right-wing populists elsewhere, such as Javier Milei in Argentina (who was elected as president) and Marine Le Pen in France (who could be).

To paint it in broad strokes, a Trump win would be considered favorable for political strongman-type leaders – like Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Trump would likely withdraw support for Ukraine to instead focus military spending on the US’s southern border with Mexico. There would be rising protectionism and trade barriers, and political questions would become even more important than economic ones for leaders everywhere. It would signal that the old liberal international order is truly gone. Re-electing President Joe Biden would move us in the opposite direction.

Looking at the three questions above, it’s obvious to me that some answers, or combinations of answers, are likelier than others. The best outcome for restoring the liberal international order would be (1) China’s economy holding up well, (2) Ukraine looking victorious, and (3) a Democrat (e.g., Biden) in the White House.

On the other hand, (1) a protracted Chinese downturn, (2) Russia looking victorious, and (3) a Republican (e.g., Trump) in the White House is a combination that would lead to a lot more global insecurity, with grabs for raw power. Business leaders should brace themselves for serious geopolitical turbulence in this case. I’d argue that the turbulence and its aftereffects, once unleashed, would shape our global economy for years to come.

President of IMD and Nestlé Professor of Strategy and Political Economy

David Bach is President of IMD and Nestlé Professor of Strategy and Political Economy. He assumed the Presidency of IMD on 1 September 2024. He is working to broaden and deepen IMD’s global impact through learning innovation, excellence in degree- and executive programs, and applied thought leadership. Recognized globally as an innovator in management education, Bach previously served as IMD’s Dean of Innovation and Programs.

May 6, 2025 • by Anna Cajot in Competitiveness

Former FBI agent Joe Navarro explains how to leverage non-verbal cues, manage power dynamics, and build trust to overcome deadlocks in negotiations....

April 24, 2025 • by Jerry Davis in Competitiveness

Many regional developers have tried and failed to emulate Silicon Valley’s VC-driven model for innovation. Detroit, the birthplace of Ford, is following an alternative route – with promising results....

Audio available

Audio available

April 16, 2025 • by Benoit F. Leleux in Competitiveness

How a private equity-backed corporate carve-out created a successful, sustainable consulting powerhouse...

April 11, 2025 • by Jim Pulcrano, Jung Eung Park, Christian Rangen in Competitiveness

Founders searching for funding must be targeted in their approach to securing a lead investor. A global survey of VCs offers valuable insights into what makes them tick....

Explore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience