IMD business school for management and leadership courses

How Companies Unknowingly Accumulate Non-Financial Debt

This article was originally published in the South China Morning Post

Firms grow by consolidation and they can only do that by putting money into features that do not require any significant technical advances.

Emotionally burdensome – that is how it feels these days to fly. And it is as painful to be a passenger as it is to work as a flight attendant. Once a promise of an adventure in the world, flying is now reduced to dread.

While the airlines play no role in shaping the Covid-19 regulations that are causing some of the traumas, they are the ones that are overburdened by non-financial debt – a sort of technical and organisational backwardness.

A few months ago, I was flying from Amsterdam via a European airline. I somehow forgot to print my boarding pass, so I needed to have it issued at the counter.

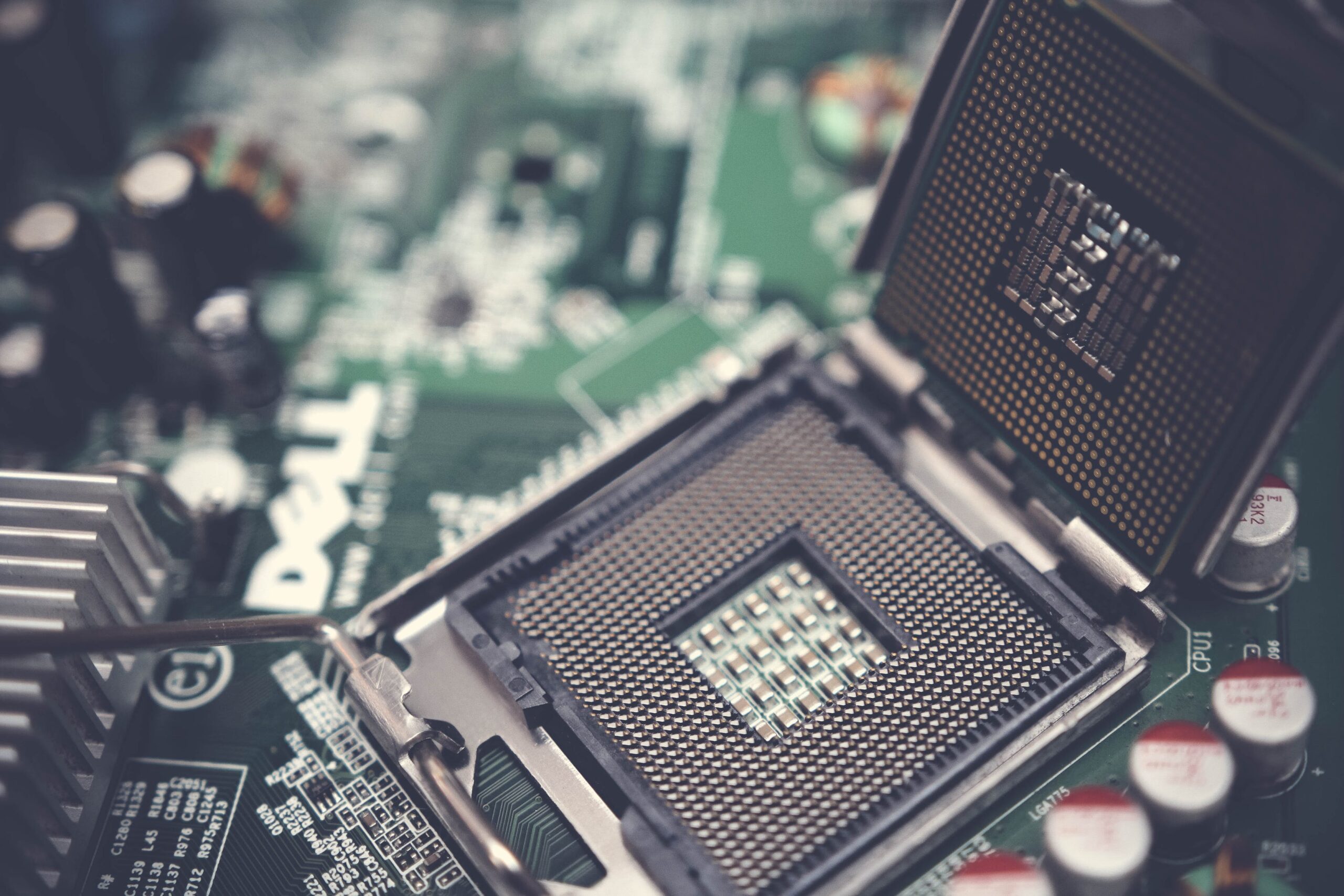

Proceeding to the help desk, I watched as a trainee handled my issue at a monitor that looked like it hadn’t been updated since the early days of personal computing. It was as if I was being served by a time machine, running backward.

Of course, we understand how things happened the way they did. The airline industry has grown by consolidation. When a carrier makes a profit, the money gets distributed back to shareholders as dividends.

As time goes by, it can only put money in product features that do not require any significant technical advances.

Meanwhile, the industry keeps accumulating non-financial debt. It is a sort of organisational debt that grows as the business expands, because its complex system continues to be stitched together by manual processes.

The resultant cost is insidiously high. But organisational debt often gets ignored because it is invisible. Nor does it immediately show up as a production bottleneck. When facing complexity, you can always throw in human staff to stave it off for a while – until the problem mushrooms into an utter nightmare.

Airlines today exhibit an extreme form of organisational debt because the underlying system has become so outmoded that it requires experts to get the most basic stuff done.

The hard truth is this it makes no sense to simplify any of the manual processes. Each of them costs so little but eliminating any would trigger a redesign of the entire system. No one can make a case for achieving simplicity.

A typical major airline today has about 30,000 employees. The average tenure for frontline workers is just four years, partly because many of these jobs are now done by contractors, but also because the work itself has become so onerous that few people can tolerate it for long.

But Toyota Motor has taught us that simplicity can be achieved by production workers who make everyday suggestions to improve the processes.

The best way to maintain good health is by paying attention to your daily diet and exercising regularly.

Toyota does it with suggestion boxes. Every one of its plant has such a box. Its engineers go through them every day and make continuous improvements. That is how the company achieves its world-class quality.

Simplicity should be the design principle behind everything we do. We must strive to eliminate complexity and make things easy for everyone to use.

And since suggestions are implemented, results compared and best practices documented, Toyota’s management knows exactly when a new piece of equipment is needed.

When a larger overhaul is due, it does not fumble in the dark because everyone in the company pays off organisational debt every day. Don’t wait till it’s too late.

Howard Yu is the LEGO chair professor of management and innovation at IMD Business School in Switzerland.