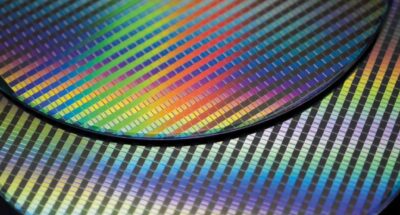

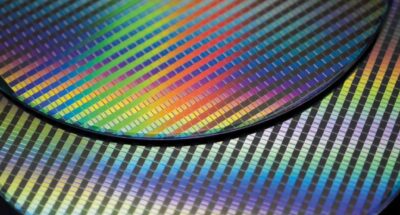

Europe needs Chips Act 2.0 to compete in digital race

Former French finance minister Bruno Le Maire says Europe needs to act urgently to secure its supply of semiconductors or face relegation to the global slow lane. ...

Audio available

November 22, 2024 • by Peter Voser in Leadership

Peter Voser, former CEO of Shell and Chairman of the Board of Directors at ABB and PSA offers his unique perspectives on guiding businesses through difficult times....

There are certain crises where you just have to tell your family: “I’ll be gone for a while.” It’s as simple as that.

Other times, like when I was leading the transformation at Shell, which I knew would take several years, it’s about setting expectations. You need to decide how you want to work, and how you want your team to work.

I tell people: “I start normally at 06:30. I will only have meetings between 08:30 and 17:00. Meetings can only be an hour, and I want half an hour between meetings.” Presentations should be to the point, not more than 10 slides.

I have no problem with switching off my phone. On a Saturday, I’ll work a couple of hours in the morning and the afternoon, but other than that I’m fully present – not checking my emails on my phone in a corner of the room.

Whether you’re the CEO or have another role in an organization, this matters. If someone sends you a slide deck at 22:00 for a meeting first thing the following morning, that’s not acceptable. The world will keep turning, even if you take the time to slow down and work more carefully.

You cannot brief absolutely everybody on everything, and you need very high levels of trust. Take risks. Take decisions. Learn, adapt, and move forward.

To manage any crisis successfully, you first have to discern what kind of crisis it is. At ABB, I managed a financial crisis. At Shell, I managed an existential crisis. What all crises have in common is that as a leader, you need to be speedy, agile, and calm. As well as this, you need to take everyone with you.

What does this look like in practice? First, choose a very small team. I managed the whole ABB crisis with eight people. Have the guts to pick those who stay calm and deliver over those who are intellectually brilliant but see the negative and hold you back. You cannot brief absolutely everybody on everything, and you need very high levels of trust. Take risks. Take decisions. Learn, adapt, and move forward.

Inclusiveness is important, but you need to decide who needs to know what. There is always a large group who want to be involved but really only need to be informed. In my experience, that includes the board. If they start to become involved, it slows things down and diverts your attention. Just keep them informed so they don’t get too nervous when they read the papers.

You learn by going through it. You have to feel your way, making decisions without knowing everything, and be willing to experiment. That makes all of us uncomfortable – it’s not how we grow up, in companies. Normally you know 100% of the risks. This is different: you need to say, “What crisis do we have? What’s the endpoint?” Then, run with it.

At ABB in 2002 we were bankrupt. The previous year we had lost $690m, the first time the company had ever gone into the red. We were existentially threatened, we were 95% geared, and we had no cash. We went to the investors. Jürgen Dormann, who was then Chairman, told them: “I don’t know anything. But Peter is here, and he can talk.” We did a big capital increase and started to get the company back on track.

Jürgen had given me a clear message: “This is a financial crisis, and you decide when you have to inform me.” The only way to solve this issue was to let one team run it – mine. We had nine divisions; we kept two to keep us alive. Jürgen looked after those while I sold off the other seven.

At ABB we had 150,000 employees. If you multiply that by their family members, you get maybe a million people. It was emotionally difficult, knowing that if we didn’t get this done, it would be felt by a million people. You have to communicate with your constituencies in the right way because they will have to answer questions at home. At one point I stopped going to the supermarket in my local village, where a lot of employees lived, because there was only one question: Will we survive?

Managing yourself is essential. I’m known for being calm, but I also had moments where I had to decide: What do I do now to make sure everything does not get out of control? When I stopped the meetings and started talking walks to get fresh air into my thinking, it made the headlines.

Another time, when things were getting heated, I took my keys out, put them on the table, and said: “You know better than I do, so I’ll just go home, and you manage the company. If you don’t want to do that, let’s calm down and think about the value we can bring.” That changed the tone of the conversation.

The most important point in a transformation is deciding exactly what you need to transform. Either your strategy is correct but you need to change something else – your culture, business model, leadership development – or your strategy is not right. Attached to that, you also need to change culture and everything else.

Let me forward to ABB’s most recent transformation, which started in 2019 when I was already chairman. It was clear then that the strategy was no longer working. We had to build a new base, attract new customers, and change our approach. We put technology at the heart of the company, designed a new purpose, and aligned everything behind that. We assessed if the CEO was the right person. We decided he was not, and I stepped in for a year to be CEO and Chair. We are now harvesting the fruits of our transformation. Our share price proves we did the right thing.

At Shell, on the other hand, nothing was “wrong” – we were $40bn in profit, with a $50bn cash flow. But as decisions were made by committees, there was no agility. So, I did something unusual: I started at the top. I told 800 senior leaders: “I only want 600 of you. You have to apply for your job again.” They could all apply for three jobs, in fact. It was fair, and people saw that. Then, once those 600 were in place, I said: “Now choose your team.” Because the transformation had to be led by them.

“Ultimately, when you are CEO or Chair, it’s up to you to lead the way, to make the big steps. That’s what you’re there for. Your gut feeling plays a role.”

I have often been told that I have the capability to take on a complex issue and bring it down to a practical level. I don’t like listening for half an hour to a complex presentation, trying to understand a sophisticated slide. At Shell I wasn’t a geologist, I was an economist. I’d say: “I can’t read a geological map, that’s why I need you. I’m savvy enough to make the right decision, but I need you to help me.”

At ABB, we had to work on our leadership and company culture. It’s important that people across the organization can hear your message – unfiltered.

Your language needs to reach your blue-collar workers. Don’t try to come across as “clever” – you’re already in the job. You can relax. My philosophy is that a CEO is only as good as the sum of their employees. You can direct them, but you can’t be better than them. Once you have that in mind, you communicate differently.

Ultimately, when you are CEO or Chair, it’s up to you to lead the way, to make the big steps. That’s what you’re there for. Your gut feeling plays a role. You won’t know all the details, so you have to learn to trust your decisions – and yourself. When you look at leaders, that is often missing. Sometimes they analyze everything to death before they make a decision. I just went for it.

This article is inspired by a keynote session at IMD’s signature Orchestrating Winning Performance program, Singapore (2024), which brings together executives from diverse sectors and geographies for a week of intense learning and sharing with IMD faculty and business experts.

Chairman of the Board of Directors of ABB Ltd

Peter Voser has served as Chairman of the Board of Directors of ABB since 2015. He also served as Chief Executive Officer of ABB from April 2019 to February 2020, and as Chief Financial Officer and Executive Committee member from 2002 to 2004. Peter was CEO of Royal Dutch Shell from 2009 to 2013 and started his career at the company in 1982. He holds a degree in business administration from Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Switzerland.

July 10, 2025 • by Bruno Le Maire in Geopolitics

Former French finance minister Bruno Le Maire says Europe needs to act urgently to secure its supply of semiconductors or face relegation to the global slow lane. ...

Audio available

Audio available

July 8, 2025 • by Mike Rosenberg in Geopolitics

A new framework encourages leaders to see the world as PLUTO – polarized, liquid, unilateral, tense, and omnirelational. It’s time to think differently and embrace stakeholder capitalism....

Audio available

Audio available

July 7, 2025 • by Richard Baldwin in Geopolitics

The mid-year economic outlook: How to read the first two quarters of Trump...

July 1, 2025 • by Mridul Kumar in Geopolitics

Mridul Kumar, India’s ambassador to Switzerland, gives his personal view of his nation’s growing role as a leader in a multipolar world....

Audio available

Audio availableExplore first person business intelligence from top minds curated for a global executive audience