How Haier gives insights into China’s radical transformation

When the definitive history of the twentieth century is written, it is entirely possible that the brightest story of that war-torn and economically challenged century will be the return of the Chinese people to a prominent role on the world stage. In fact, today, in our time of petty economic bickering and trade war posturing, it is still worthwhile to reflect on all that has been accomplished by the realization of Deng Xiaoping’s re-engineering of what had begun as early as the 1960s, under Zhou Enlai’s guidance, as the Four Modernizations (agriculture, industry, national defense, and science and technology) and which today has grown into the modern Chinese economy.

I feel as if I have had a privileged view point of this saga, as my family and I first moved to China in 1980, just as the reforms were beginning in the industrial sector. I have also been fortunate to return to China in one form of work engagement or another for each of the following 40 years. Like all such stories, this is both about seeing the forest and the trees. While the changes in the forest are genuinely impressive, it is the individual tree stories that provide insights into what comes next.

In 1970, during the so-called Cultural Revolution period, China’s exports to the world accounted for only 2.49% of its diminished GDP ($92.6 billion in current US dollars), while imports represented only 2.46% for that same year. For a big nation, of then 818.3 million people, this was as closed as one might imagine that a closed economy might ever be. In 1990, ten years after the industrial reforms had begun, two-thirds of China’s population (755.8 million people out of 1.135 billion) were still living below the World Bank poverty line of $USD 1.90 daily.

Today’s China has moved way beyond these numbers: China’s GDP in 2018 reached an estimated $USD 1237.70 billion, ranking it second in the world in nominal terms, and China is by far the world’s largest exporter as well. According to World Bank data, only .7% of the Chinese population was living below the poverty level in 2015. This is a story of national achievement that is unmatched in modern macroeconomic history, and which I believe is a testament not only to the labors of the Chinese people, but to the catalytic effects of opening-up an economy to external influences. But there is also a story unfolding at the microeconomic level that reinforces this.

In January of this year, in the city of Qingdao, at the annual innovation summit of the venerable home appliance giant, Haier Corporation, the 2018 Nobel laureate in Economics, Professor Paul Romer, observed that “We are better off being part of a bigger ecosystem. We are better off inviting others in!” To which he later added “Progress, then, is very much about “who we are” [as an ecosystem]. No longer dividing us versus them.” This is an important message in today’s “anti-Global” age.

Several years ago, I wrote a piece for Forbes, entitled “Made in China, Smarter Companies?”. The argument was that Chinese companies were building a new future on the basis of learning better and faster than their foreign competitors. At that time, I was referring to simple listening and responding. Today, however, at the level of the firm and below, what we are seeing are organizations that are attracting and harvesting more new ideas by virtue of being radically open and entrepreneurial.

At Haier, the firm that I know best in my role as one of their Management Innovation Consultants, the new frontier in innovation is Organizational, which has been best expressed in the development of a Platform Organization which attracts new ideas from anywhere, and then by relying on the Rendanheyi management philosophy which has evolved at Haier over more than three decades, and which encourages autonomous micro-enterprises to exploit these new ideas while relying on some support from the Haier platform to which they have chosen to rest upon. The range and rhythm of activity is astonishing and has led to the rapid infusion of new ideas into what has traditionally been a large, old-economy, incumbent market leader.

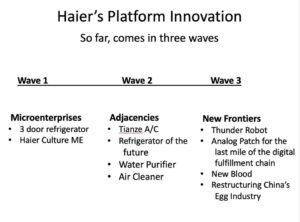

Haier’s latest experiment with Organizational Innovation has occurred in stages, each stage progressively stretching the idea-domains at work beyond the traditional center based on familiar home appliances:

Each of these waves of platform innovation has opened Haier up to participation in an increasingly more valuable set of ecosystems. Haier’s participation in each is characterized by self-evolving, autonomous microenterprises, that typically are responsible for end-to-end development of their ideas. These are important choices as they increasingly bring in more ideas from the outside and power a continuous pursuit of the future by reducing the barriers between inside and outside.

China’s continuing long march from the autarky of the 1960s and 70s, doing everything by oneself, to establishing a presence of being everywhere today, is consistent in my mind with the experimentation that Haier is enabling, and this also affects the way that the rest of us will see our own organizations developing in the future. According to platform strategist, Simone Cicero, such organizations: find new growth at the edges of what they are involved in, develop organizations that facilitate emergence, rely on autonomous energies to take command (so that leadership devolves to the microenterprises), and transform their identify to that of the ecosystem. This is not easy, nor natural to do for most companies. Yet, openness to the world, and to new ideas is not only radically changing the Chinese economy but has the power to change corporate innovation as well.

William A. Fischer is a Professor of Innovation Management at IMD. He co-founded and co-directs the IMD program on Driving Strategic Innovation

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

The Brics emerging markets are once again touting their ambition to build a world less dependent on the US dollar. Leading the latest push is a new guarantee fund, to curb investment risk and support financing in the bloc, something discussed at l...

When the leaders of the Brics group of developing countries gather on Sunday for their 17th annual summit, the backdrop is one of the most geopolitically volatile the bloc has faced in years, with trade tension, regional conflicts and energy insta...

When Chinese Premier Li Qiang addressed the World Economic Forum’s “Summer Davos” in Tianjin, China, his message was clear: China must become a “mega-sized” consumption powerhouse. Not just the world’s factory, but its market too. His words underl...

For years, multinational companies operated in the Middle East with the belief that while politics could flare up, trade would largely continue. That assumption, while once reasonable, is now under serious strain. The war between Israel and Iran l...

To understand America’s aggressive shift on trade, you must first grasp the silent, slow building, decades-long erosion of American middle-class prosperity. This shift began well before President Trump and will outlive him. It is rooted in the col...

After more than a decade of war and isolation, Syria is edging back into the global economy. The signs are familiar: commercial flights have resumed, sanctions are being eased and its debts are being cleared. Gulf investors are circling. Infrastru...

The Great Trade Hack by Richard Baldwin explains how Trump’s 2025 tariff blitz wasn’t economic strategy. It was grievance politics. Tariffs, Baldwin shows, are political placebos that won’t fix the U.S. economy but could fracture the global trade ...

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

in Gensler, Gary (Ed.); Johnson, Simon (Ed.); Panizza Ugo (Ed.); Weder di Mauro, Beatrice (Ed.) / The Economic Consequences of The Second Trump Administration: A Preliminary Assessment, pp. 239-244 / PAris: CEPR Press, 2025

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Published by International Institute for Management Development ©2025

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications

Research Information & Knowledge Hub for additional information on IMD publications