IMD business school for management and leadership courses

Published on October 7th, 2025

What Netflix’s Real Origin Story Teaches Us About Conquering the AI Storm

Published on October 7th, 2025

History’s real disruptors often hide beneath the user interface. Reed Hastings taught us where untapped data hides.

The morning sun glared off the glass-and-steel cube of Blockbuster’s corporate headquarters. A private jet from California had just taxied to a halt. Inside the chilled and spotless boardroom, CEO John Antioco waited, impeccable in a tailored suit and loafers “probably worth more than my car,” as one visitor would later recall.

The visitors: Netflix CEO Reed Hastings, cofounder Marc Randolph, and their CFO. After months of relentless pursuit, they had finally secured a last-minute audience. Hastings, ever precise, had calculated: If they left California at 5:00 a.m. on a chartered flight, they’d arrive just in time. “Probably even have enough time to grab an espresso.”

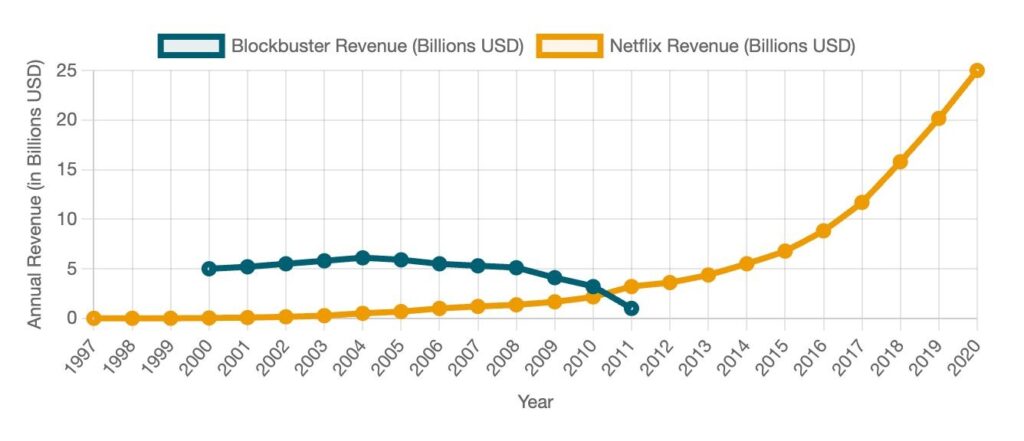

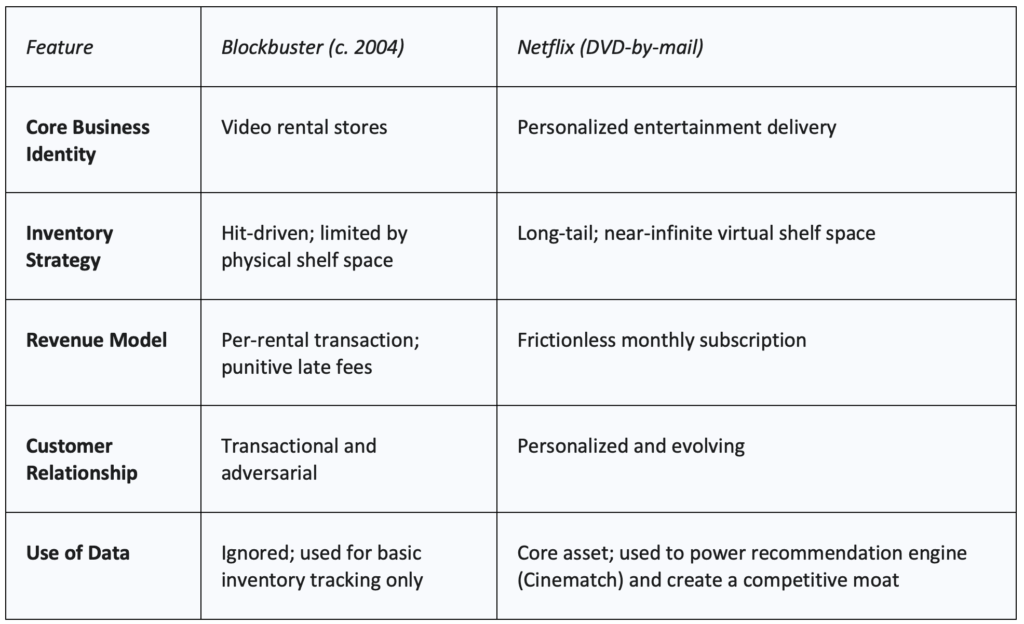

At the time, Netflix was a scrappy, cash-burning DVD-by-mail startup. Blockbuster, a $6 billion behemoth with near-total market dominance. Hastings came with a bold proposal:

Why not join forces? Netflix would run Blockbuster’s online and DVD-by-mail operations. Blockbuster, in turn, could continue to focus on its sprawling network of 7,700 brick-and-mortar stores. Together, Hastings argued, they could future-proof the entire home entertainment kingdom.

For a moment, the room went still. Antioco leaned in, nodding thoughtfully. He was playing the part of an open-minded listener. Then, his general counsel cut in with a question everyone knew was coming:

“If we were to buy you … what are you thinking? I mean, a number. What are we talking about here?”

Hastings had prepared for this. “Fifty million dollars,” he replied calmly.

Antioco’s veneer cracked; the corner of his mouth twitched as he fought back a laugh. He leaned back and delivered his verdict: Dot-com hysteria was overblown, and Netflix was a trivial niche player.

Other executives around the table chuckled, piling on. The meeting was over. Reed Hastings and his team were shown the door.

The Real Killer: A Format, Not a Stream

Here’s what most people get wrong about Blockbuster. It wasn’t Internet streaming that killed it. Netflix didn’t even stream its first movie until 2007. By then, Blockbuster’s stock had already been in free fall for years. It wasn’t the Internet. It wasn’t digital disruption.

It was the plastic disc.

The shift from VHS to DVD seemed trivial. It was a change so incremental it seemed harmless. A cassette replaced by a shiny little circle.

That destroyed Blockbuster. Because beneath the surface, the new format flipped the entire business model on its head. DVDs were cheaper to buy and easier to ship, and they required no rewinding. Most of all, DVDs made subscriptions viable. And that simple format change upended everything.

Fast-forward to today. A similar misdirection is underway.

The New Misdirection: The “LLM Apocalypse”

In boardrooms around the world, there’s a low hum of anxiety, and just beneath the surface, there’s a tremor that won’t go away.

- Nvidia’s valuation surges past $4 trillion. TSMC, the factory behind it, also surpasses $1 trillion.

- Mark Zuckerberg pours billions into AI infrastructure, poaching top researchers from OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic.

- Tesla’s revenue dips, but the stock holds, floating on a dream of “Robotaxis.”

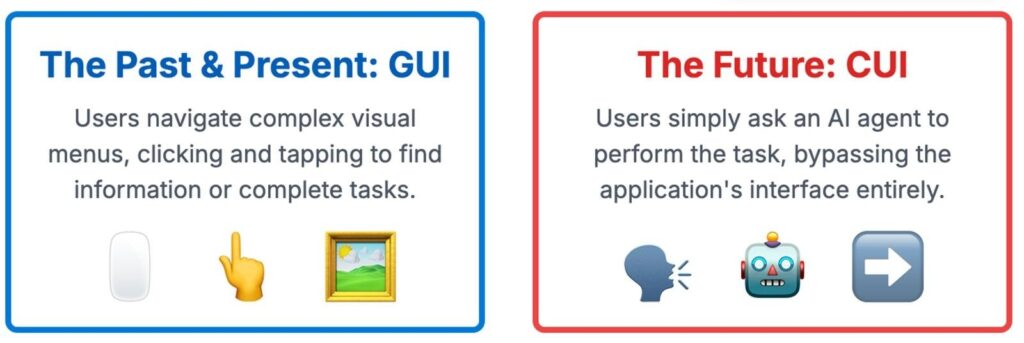

A chilling thought is spreading among executives: What if LLMs (Large Language Models) aren’t just smart chatbots but fast-evolving agents that collapse everything you’ve built into a single line of text?

- Users won’t open Spotify. They’ll just say, “Play me something chill.”

- They won’t scroll Booking.com. They’ll ask, “Book me the best hotel and flight under $500.”

- They won’t browse The Wall Street Journal. They’ll prompt, “What should I know about the market today?”

Your app. Your site. Your UX. Your brand gets flattened. Seen by no one.

Even policymakers are catching on. The White House’s AI action plan calls for open-source models just to ensure the AI revolution won’t be confined to a few tech giants.

Sure, agentic AI is the shiny new interface. But what if that’s not the real disruption? History tells us: when interfaces shift, incumbents rarely lose because of tech. They lose because they misread the threat.

We’ve Heard the Prophecy Before

In 2011, Marc Andreessen famously wrote, “Software is eating the world.” And he was right, but only halfway.

Software didn’t kill Visa or JPMorgan. Booking.com didn’t wipe out Marriott or Hilton. Google Flights didn’t kill Delta or Singapore Airlines.

The value still accrues to the operators, not just to the software platforms around them.

And now comes a new prophecy: “LLMs will eat the world.”

So let’s not panic. But remember: Netflix didn’t kill Blockbuster because it streamed movies. That’s just the convenient narrative. The real story is a fatal error Blockbuster inflicted on itself. They failed to see that the shift from VHS to DVD unleashed a data revolution.

It’s never just the interface that changes the game. It’s what the interface enables. New data flows. New consumer habits. New economic logic.

While Blockbuster Shut Its Ears, Netflix Listened

The return flight to Santa Barbara was silent. Reed Hastings, Marc Randolph, and their CFO sat quietly, absorbing the sting of rejection. “It was a long, quiet ride back to the airport,” Randolph recalled. “We didn’t have a lot to say to each other on the plane either.”

There would be no merger. No partnership. Only competition. And that’s when Blockbuster’s unraveling began.

Let’s roll back the clock.

In the VHS era, movie studios like Universal and Sony priced new releases between $70 and $100 per tape, far too expensive for consumers to buy, but perfect for rentals. Blockbuster became the gatekeeper of home entertainment.

Blockbuster had something priceless. Every day, customers walked into stores, browsed shelves, asked questions, made choices. It’s a goldmine of behavioral data: what they looked for, what they rented, what they returned early, what they couldn’t find.

But Blockbuster captured none of it.

The IT systems were ancient. No major upgrade in nearly 20 years. They still thought like a logistics company, not a data company. Blockbuster was flying data-blind.

And suddenly, the barriers that once protected Blockbuster—cost and bulk of VHS—disappeared.

- VHS: Bulky, expensive ($100 per tape), limited shelf space. Blockbuster mastered this logistics puzzle. They knew inventory, not insight.

- DVD: Slim, cheap ($20 per disc), sold everywhere (Walmart, Costco). Why would a customer pay $4 to rent a movie for a few nights when they could own it forever for just $15?Netflix could also afford a vast library, catering to the “long tail” of niche tastes Blockbuster ignored.

Reed Hastings was building something vastly different. In 1999, Netflix introduced a flat-rate subscription: $19.95/month, unlimited DVDs, no late fees, no due dates. Just endless choice by mail.

But choice brought a new challenge: discovery.

With tens of thousands of titles, how do users find what they’ll love? That’s where Netflix found its unfair advantage: a recommendation algorithm called Cinematch.

Cinematch soon became the growth engine. Every five-star movie rating from a customer trained the system. Every rent and return became new data points. Over time, the algorithm became eerily good at predicting taste. Not just what you liked, but what you didn’t yet know you’d love.

The more people rated DVDs, the smarter the system became. And the smarter it got, the more people rented. It was a perfect feedback loop. That’s how Netflix monetized the “long tail,” like indie films, foreign dramas, cult favorites. Twenty percent of Netflix’s revenue came from such overlooked gems, titles Blockbuster never bothered to stock.

In 2006, Reed Hastings doubled down and launched the Netflix Prize: a $1 million bounty for anyone who could improve Cinematch’s accuracy by 10%. By then, Netflix wasn’t a DVD company. It was a personalization company. A data company disguised as a movie service.

And Blockbuster? They kept buying expensive VHS tapes. They treated DVDs as a side hustle. They didn’t think customers cared about discovery. They never built a real recommendation engine.

Except for one lone franchisee who knew better.

A Southern Holdout

In Longview, Texas, a small-town franchisee named Alan Payne decided to copy Netflix. Not its technology, but its thinking.

He expanded his local DVD inventory. Leaned into the long tail. Created a “World Cinema” aisle two shelves deep. And he made recommendations by hand. No algorithms. Just paper, pen, and a smile. He knew people by name. He remembered what they rented last week. He asked questions and actually listened.

And it worked. His stores became the most profitable in the entire Blockbuster network. They were also the last to survive after bankruptcy, still flickering long after the corporate lights went out.

Payne had begged HQ to listen. He had offered to share what was working. He had asked for someone, anyone, to call back. No one did. John Antioco never replied. He was too busy opening more video stores.

That’s how one company rose to greatness while the other became a Harvard Business School case study in what not to do.

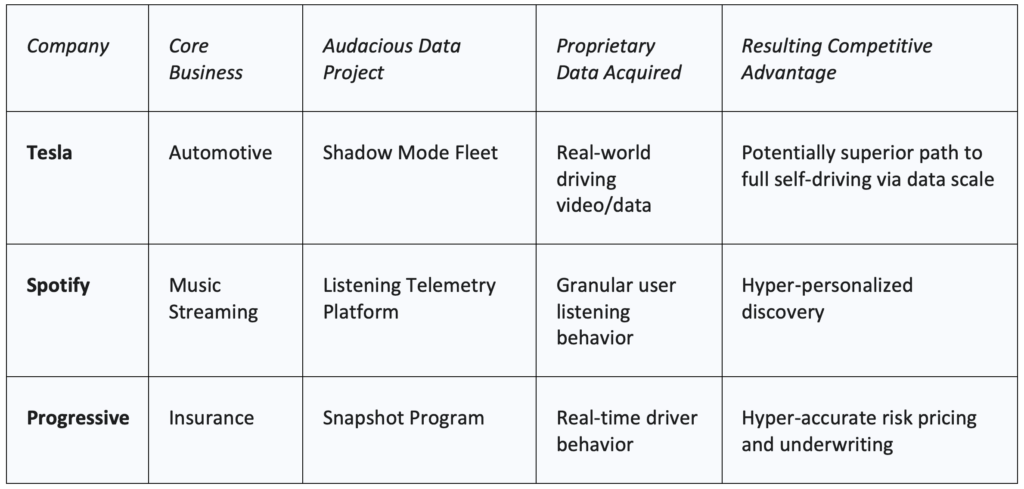

The New Moat: Proprietary Data in an AI World

The same failure of curiosity that doomed Blockbuster could haunt today’s AI-wary executives. But here’s the thing: You don’t need to build the next ChatGPT. Focus on what no general-purpose model can replicate: your proprietary data. That’s your moat.

As one industry observer put it, “Data is the asset that unlocks future business models.” And if that data is uniquely yours, it can keep you relevant, even as foundational AI models become commoditized.

Look at self-driving cars. Tesla’s Autopilot. Or Waymo’s driverless taxis.

None of these systems survive on software code alone. They run on massive volumes of real-world sensor data—radars, cameras, GPS—from actual cars driving actual roads. Tesla’s 5 million‑plus cars now upload roughly 50 billion miles of driving data each year.

Robotaxis have no shortcut without road data. The same applies elsewhere.

Spotify doesn’t just know what songs exist. It knows how you listen. What you skip. What you play on repeat. What you cue up during a run or when winding down at midnight.

It has years of behavioral signals that no Internet-trained LLM can touch. A generic LLM may know famous bands and lyrics, but Spotify knows you. That’s how Spotify can confidently roll out features like Discover Weekly, built on a proprietary understanding of music taste, that others can’t.

Or take something even older: insurance.

Progressive Insurance, founded in the 1930s, made a radical move in the 2010s, straight out of Netflix’s playbook. Through its Snapshot program, Progressive gave drivers a plug-in device (and later an app) that tracked real-world behavior like hard braking, late-night driving, and acceleration patterns.

Over a million drivers opted in, eager for lower premiums if they could prove they were safer behind the wheel. In return, Progressive got what no competitor had: behavioral driving data at scale. It was about pattern recognition.

Here’s a century-old insurer turning everyday cars into moving data centers and building a moat no tech giant could easily cross.

The Executive Personality That Wins

These strategies aren’t technically hard. But they demand something rarer. Leaders must be radically open to new ideas. They need to be humble enough to admit that even decades of experience might need an infusion of curiosity.

John Antioco came from 7-Eleven. He had street smarts. Operational chops. But at Blockbuster, his instincts led him astray. He pushed toys and apparel into stores to boost sales volume. What edge did Blockbuster have over Walmart or Costco? None. Customers weren’t there to buy Barbie dolls. They came to rent Frozen. (Popcorn and candy were the only upsells that ever worked.)

These gimmicks weren’t new. Blockbuster had tried them before. Antioco thought this time would be different. It wasn’t.

Then came his next move. He launched Blockbuster’s own online service to rival Netflix. But the offering was thin. The catalog was limited. And without real-time data or personalization, the experience felt empty. A ghost town compared to Netflix’s vibrant library.

So Antioco threw a Hail Mary. He scrapped late fees altogether. Customers could now return DVDs to the store and immediately pick out something new. No penalties, no friction.

But friction had a purpose.

Without the nudge of a deadline, customers didn’t return the big releases. Soon, shelves were empty of the latest hits. Those were the very titles that brought people in. The system broke down. It wasn’t innovation; it was self-sabotage.

And yet, Antioco pressed ahead. He ordered every store, including franchises, to eliminate late fees.

The lone holdout? Again, Alan Payne.

Payne resisted. In his stores, late fees stayed. He didn’t frame it as punishment; he framed it as fairness. He explained to customers that those fees kept inventory flowing. If someone didn’t bring back Gladiator, someone else couldn’t watch Gladiator.

And it worked. His customers understood. Payne’s stores stayed stocked. They were the most profitable Blockbusters in the country.

And what did Antioco do with this data point? He ignored it. Again.

Meanwhile, Reed Hastings did the opposite. He made a habit of embracing dissent.

At one point, Hastings debated whether Netflix should invest in original children’s content. His instinct said no. He figured adults made household decisions anyway.

But instead of deciding in isolation, he opened up the floor. At a company town hall, Hastings invited every employee to weigh in. He split them into small huddles, then reconvened for a plenary debate.

Again and again, parents in the hall delivered the same message: “When kids want something, parents buy it.”

So Hastings changed his mind. And Netflix changed course.

Antioco dismissed feedback from customers, franchisees, and even financial results. Hastings invited it. He turned contradiction into clarity. He listened.

And that, in the age of AI, might be the ultimate competitive advantage. Because the companies that win won’t be the ones that know best. They’ll be the ones that learn best.

Practical Key Takeaways: Digging Your Data Moat Now

So what does all this mean if you’re not OpenAI or DeepMind but still want to stay future-ready? It means thinking less like a tech tourist and more like Reed Hastings. Or Spotify. Or Progressive.

Start by asking:

- What “data exhaust” does my business already produce? How can I start bottling it?

- How can every customer interaction, online or offline, become fuel for smarter decisions, better service, and a moat that generic AI can’t cross?

Here are three principles to guide you:

1. Instrument Everything (Within Reason)

Whenever customers interact with your product or service, look for ways to capture that behavior, automatically and seamlessly.

- Run a retail chain? Are you tracking foot traffic flows or product pairings at checkout?

- Have a website? What are your clickstreams, search terms, or abandoned carts telling you?

- Offer a service? Can you capture outcomes or feedback without annoying your users?

Data isn’t a byproduct. It’s working capital. If you’re not collecting it, you’re leaving value on the floor. (With full respect for privacy, of course.)

2. Don’t Just Store Data; Exploit It

Having terabytes of logs means nothing if they sit idle. You don’t need a lab. But you do need a team, even a small one, whose job is to mine for “aha” moments.

Remember Netflix’s $1 million prize to improve its recommendation algorithm? Blockbuster had mountains of data too. It just never bothered to open the mine. Don’t repeat that mistake.

Even basic analysis, like segmenting customers or A/B testing or trend spotting, can uncover insights your competitors miss.

And over time, you can build something more powerful: a learning loop. The more people use your product, the smarter it gets.

Just like Spotify’s Discover Weekly. Or Progressive’s pricing engine.

3. Broaden and Deepen Your Moat

Go after the data that doesn’t exist yet but should.

- What knowledge in your business hasn’t been digitized?

- What patterns could you be capturing that no one else is thinking about?

- What would be nearly impossible for a competitor to recreate?

Think of Google sending camera-equipped cars around the world to build Street View. It was bold. It was expensive. But it gave them an irreplaceable data layer and a monopoly in mapping.

And that’s the point.

You want to be the reason the AI stumbles. If a customer asks an AI assistant about your space, and your data isn’t in the mix, the answer will be mediocre—a “meh.”

That gives you leverage. License your data. Fuel a partnership. Or keep it proprietary so your product wins on experience alone.

Now it’s your turn.

What kind of data will you collect at scale that a generic AI model can never find on the open web?

- Maybe it’s IoT sensors tracking every movement across your factory floor.

- Maybe it’s trend-sharing from a data cooperative you build with trusted partners.

- Or maybe it’s off-script conversations and frontline observations that algorithms can’t reach, only you can.

Cleverness without context is useless. An idiot savant may dazzle but can’t deliver. In the end, it’s your domain expertise, the data only your business can generate, that turns LLMs from a looming threat into your most powerful tailwind.

Epilogue: The Last Blockbuster

When Alan Payne finally shut the doors of the last Blockbuster stores under his care, it felt more like a wake than a closing. “Every store we closed, it was another sob party,” he recalled. “Customers crying, employees crying.” People didn’t just come for the clearance DVDs. They came to say goodbye. To their Friday nights, their childhoods, their rituals. One customer, half-joking, with misty eyes, told him, “You’re ripping my childhood away from me.”

Today, in Bend, Oregon, the very last Blockbuster on Earth still stands, not as a business but as a living museum. Tourists fly in from around the world to wander its blue-and-gold aisles, to run their fingers along faded plastic cases, to feel something. They buy Blockbuster T-shirts, pose by the drop box, and pick up souvenir membership cards as if they were relics from a vanished civilization. Because they are.

The store’s owner, Ken Tisher, has been likened to a zookeeper tending the last creature of its kind. “At some point,” he admits, “people may stop coming to look at that animal.” But until then, he’s just “enjoying the run.”

Blockbuster had its chances: a loyal customer base, a golden opportunity to buy Netflix. Yet it was defeated by its own indifference, by leaders who stopped being curious. They clung to the old playbook: Open more stores; sign more deals; keep the shelves full.

And so, all that remains are fading memories and a lone storefront that stands as a shrine.